How Ushahidi Technology Can be Applied in Sudan?

It is 2008, the Kenyan election has just started. Violence erupts around the country after widespread perception that the count of the presidential election was modified in favour of then Kenyan president Mwai Kibaki, leaving millions of citizens having no way of comprehending what is happening on the ground and how can they stay safe.

‘Any techies out there willing to do a mashup of where the violence and destruction is occurring and put it on a map?’ writes Kenyan blogger Ory Okolloh in Kenyan Pundit. A few days later, along with four technologists, they create a web-based platform to crowdsource reports from citizens via SMS and the web. These reports were then geolocated and timestamped, sending alerts back to the people on the ground and citizens watching from around the world. People now had a way to understand what was happening, where, and how to stay safe. Over 40,000 reports were submitted, verified and sent. They called it Ushahidi, which is the Swahili word for ‘testimony’ or ‘witness’.

In the last 10 years, with a global team of a little over 30 experts from 10 countries, Ushahidi has been used more than 150,000 times in over 160 countries, crowdsourcing more than 50 million reports.

According to Ushahidi:

‘We believe Technology can help marginalised people raise their voices so those who provide support and assistance will listen and respond more effectively bringing global attention and targeted solutions to problems that need to be solved.’

The platform was founded for crisis response, election monitoring and human rights reporting. It is also used for environmental monitoring, citizen journalism, free and fair media, public service delivery, global health initiatives and much more.

It works by collecting data from crowds using social media, RSS feed, email and SMS messages. This data is then managed and combined using keywords, geolocation and semantic tagging. It can later be visualised and analysed to make decisions accurately or adjust activities to improve impact.

In the recent years, the platform has been used in many ways such as the following:

- The Syria Tracker crises map: It is the longest standing reporting tool in Syria and its reports have been used by the United Nations (UN), USAID and the Washington Post. The tracker uses mapping system to gather, verify and pinpoints reports of violence on a crisis map based on crowdsourced text, photo and video reports. Once verified by official sources or other citizen reports, Syria Tracker sends alerts to Syrians, external relief providers and decision-makers so they can respond. In early 2014, Syria Tracker even warned of an outbreak of polio days before other news outlets, thanks to early civilian reports.

- Reclaim Naija: In 2011, Reclaim Naija became a national platform for ordinary citizens and organisations to work together to engage the country in encouraging a peaceful, free and fair election. The Ushahidi platform was used by Reclaim Naija as a crowdsourcing tool for election monitoring and accountability. Citizens were encouraged to report any incidents through the platform so electoral and security authorities could respond by reallocating resources to specific polling stations. As a result, voter turnout increased by 8% because of increased trust in the process. The 2011 Nigerian Election demonstrates one example of how the Ushahidi platform has been used effectively in election monitoring. There are many more examples over the last 10 years.

- Mapping Media Freedom: A platform that uses Ushahidi to map and categorize incidents of threats to the press, highlighting the need to protect journalists. It has been operating since 2014 as a joint undertaking with the European Federation of Journalists partially funded by the European Commission, monitoring the media environment in 42 European and neighbouring countries.

Organisations in Sudan face many roadblocks in obtaining reliable information and first-hand accounts of incidents. Ushahidi’s platform can be used to overcome these barriers, empower people to come to come forward, and help authorities and organisations make better decisions. The platform can be used in many areas in Sudan such as:

- Mapping in-need families to help volunteers, NGOs and relief foundations better distribute their resources and personal

- Anonymously reporting acts of corruption

- Geo-mapping certain disease cases and early outbreak detection

- Documenting sexual harassment and rape to make cities and communities safer

If implemented in Sudan, this technology can help reduce corruption, make communities safer by identifying where the problems are, and pushing authorities and administrators to act.

It can also hugely impact relief effort by providing real-time reports of the needs, including geographical location, which can reduce the resources needed, improve efficiency and eventually save lives.

Most importantly, the technology will solve a huge issue that both private and governmental organisations face in Sudan, which is the lack of accurate and reliable data; and as we all know if there are poor statistic, the problem is not visible, decisions are inaccurate, and efforts do not yield the desired results.

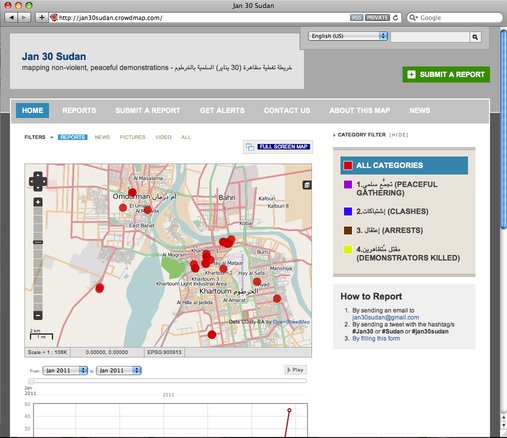

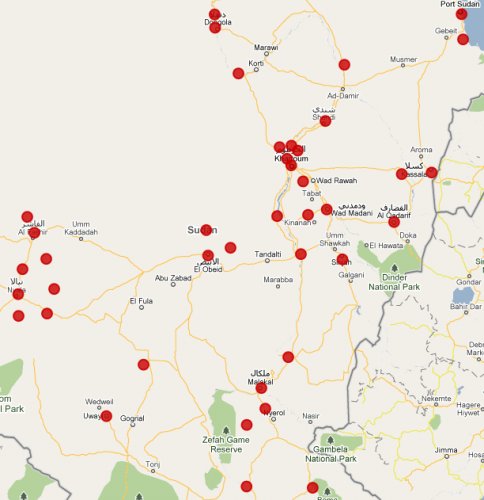

Currently, the technology is being used to document and track incidents of the ongoing Sudanese uprising. These initiatives were developed and implemented by Bellingcat, an open-source investigation service (https://sure2018.ushahidi.io/views/map), and AYIN Network, which documents daily incidents in Sudan (https://sudanuprising.ushahidi.io/views/map).

Powerful use of @ushahidi to document the Sudan uprising that started last week. Follow it here. https://t.co/AyZxhPtXFb

— Ushahidi (@ushahidi) December 26, 2018

Mohammed Jalad is a 24-year-old engineer, tech enthusiast and introvert currently living in Malaysia. Exploring writing for the first time, Mohammed will delve into topics of technology and education as well as self-help and motivation.

Mohammed Jalad is a 24-year-old engineer, tech enthusiast and introvert currently living in Malaysia. Exploring writing for the first time, Mohammed will delve into topics of technology and education as well as self-help and motivation.