Behind Award-Winning Film “AL-SIT” and Filmmaker Suzannah Mirghani

After the success of Amjad Abu Alala’s You Will Die at Twenty, we’ve witnessed a wave of Sudanese films and documentaries, making it to international screens and grabbing awards at international film festivals.

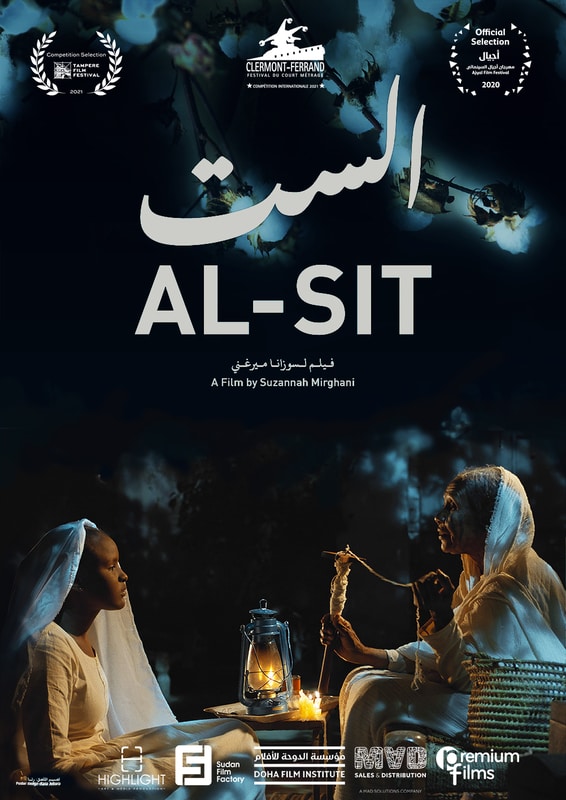

Most recently, AL-SIT (2020), a story of a young girl’s arranged marriage in a cotton-farming village in Sudan, has won the Grand Prix award at the Tampere International Film Festival 2021 in Finland. This automatically qualifies the short film to enter the competition category for short films at the Academy Awards (Oscars).

AL-SIT has bagged many awards since its world premiere at Clermont-Ferrand, one of the biggest film festivals for short films, where it won the Canal+ award in January 2021. It was the first Sudanese film to ever screen in the Clermont-Ferrand Short FilmFest Pro competition. The short film won the Excellence in Women’s Filmmaking Award at The European Independent Film Festival in Paris, won special mention at Malmo Arab Film Festival, and more.

Photo credit: Tariq Al-Fatieh

AL-SIT is written, directed, and produced by Qatar-based Sudanese-Russian filmmaker Suzannah Mirghani, a well-known personality in the Sudan’s film industry. Her previous shorts include CARAVAN (2016) and HIND’S DREAM (2014), and she has been selected to be a jury member of Sudan International Film Festival (SIFF) 2020. An Assistant Director for Publications at the Center for International and Regional Studies (CIRS) at Georgetown University in Qatar, Mirghani is a writer, researcher, and independent filmmaker, highlighting stories from the Arab world. She is a media studies and museum studies graduate, and publishes creative and scholarly work on a variety of cultural issues. Being of mixed race, Sudanese and Russian, Mirghani is most interested in stories that examine the complexity of identity.

500 Words Magazine interviews the well-acclaimed filmmaker Suzannah Mirghani about her award-winning film AL-SIT, the Sudanese film industry, making Sudanese films, and more.

What inspired the story of AL-SIT?

AL-SIT is a mixture of childhood memories from when I lived in Sudan. Of these, two specific ideas sparked the story: my memories of cotton and my memories of grandmothers. I remember visiting cotton fields in Sudan and being struck by their beauty. Seeing a cotton plant for the first time made me think how strange it was that something could be so simultaneously beautiful and useful.

We’d then come back to the house and watch old women spinning raw cotton into thread. I loved listening to Sudanese grandmothers talking, because they always told such interesting, funny, and poignant stories. They were a cabal, a coven, a community, and they were fiercely independent—at that stage of their life, they answered to no one; in fact, they gained a huge amount of respect and power, and they ruled over the household. There was something otherworldly and magical about seeing old women spinning heaps of thread. Especially at night, by candlelight, it was almost as though they were ancient characters in a fairytale. This is a vision that has haunted me for a long time, and one that I knew I wanted to revisit and recreate somehow.

How important and real is the message and story of AL-SIT?

I portray multiple Sudanese sociopolitical issues in this film, among them: arranged marriages, child marriages, filial piety, stubborn traditionalism, economic exploitation, women’s rights, and power struggles between family members as well as between genders. I’ve often been asked why I tackle so many subjects in one short film. My answer: This is life. Any one moment of someone’s life is filled with events, relationships, tensions, and desires, and so I think it’s only right that a 20-minute family drama will necessarily explore opposing philosophies of life. All of these elements might not be central to the story, but they imbue the atmosphere and add richness to the characters and their social surroundings.

Although the themes are multiple, and the underlying story is complex, the setting is quite simple and most of the film takes place in the yard, or “hosh,” of a Sudanese family home. AL-SIT is the story of an arranged marriage of a young girl, Nafisa, who is beautifully embodied in the very talented first-time actor Mihad Murtada. The girl is an innocent bystander in the center of a power struggle between various forces: between her parents and her grandmother, who is given flesh and blood by the great stage actor Rabeha Mahmoud; between different age groups and generational ideologies; and between modernity and tradition. These tensions are all brewing at the same time as each character attempts to gain control of not only the current situation, but to also claim stakes in the future.

What are some of the challenges you’ve faced making the film?

The first challenge of making a film is always financial. It’s free to write a story, but turning a script into a living, breathing event is costly. While I was fortunate to receive a generous production grant from the Doha Film Institute, it wasn’t enough to cover all expenses for the film. I was so determined to get this film made. I decided to contribute my own personal investment, making me the majority funder and producer. I also received financial input from my sister Julietta Mirghani and my husband Rodney X Sharkey, who came on board as associate producers. In addition, Maysaa Almumin, Kuwaiti filmmaker and assistant professor at VCUarts Qatar, joined as associate producer by contributing institutional design support and funding.

I came back to Sudan to make this film accompanied by my producing partner Eiman Mirghani, whose family generously welcomed us, and helped us navigate through the first few days. This was our first taste of post-revolution Sudan, and we were both amazed at all the changes the country had been through. We spent the first few days exploring what was new about Khartoum, and meeting with old friends. When we arrived, all I had was a script and some funds, and so the main obstacle was literally everything. The question was: “how do we make a film in Sudan?”

How did you find your crew?

To my surprise and delight, after just a few days on the ground, we began to assemble our entire crew. Salwa Al Khalifa was my assistant director, but also a miracle worker. To this day, when I hear about how many fires she put out behind the scenes, I’m amazed and grateful. Through a chain reaction, Salwa introduced us to everyone we would be working with: Line Producer Abdullah Osman, whose talent is to make the impossible possible on a daily basis, solving a multitude of problems with casual ease; Production Manager Enan Mohammed, whose impeccable organisation and positive energy is reflected in the film; and Second Assistant Director Atif Araky, a being of boundless energy who never seemed to tire.

Khalid Awad, the cinematographer, is a philosopher with a camera and he led the camera crew with a great sense of comradery. While we worked closely together to put together the storyboard and shot list, the film is shot through his eyes and expertise, and the way it looks and feels is really down to his singular vision. Moez Al Hajar was a wizard with light and shadows, and his crew all worked beautifully together. Art Director Sara Awad, worked tirelessly and made magic happen on set by turning the most ordinary, everyday space into an extraordinary set. Makeup Artist Rayan Ibrahim and Costume Designer Mohamed Elmur “Simba” made the characters look and feel exactly as I had imagined them in the script, perhaps even better. We worked with an entirely Sudanese cast and crew, with the exception of the Bassam Lebbos, a talented Sound Recordist, who joined us from Lebanon. For the duration of the shoot, he was an honorary Sudanese and took part fully in the Sudanese way of life.

How did Sudan Film Factory and Doha Film Institute (DFI) support your film?

We held auditions at the Sudan Film Factory to find our key actors, including first-time actors, Mihad Murtada, who so perfectly plays Nafisa; Mohammed Magdi, who so brilliantly plays Nadir; Fatma Farid, who plays Faiza, and whose melancholic acapella song closes the film; Entesar Osman, who plays Faiza’s mother; Talaat Farid, who plays Babiker; and Murtada Eltayeb, who plays the driver. It was a beautiful sight to watch these actors work together for the first time and to embody the characters I had only ever imagined. The older actors like Rabeha Mahmoud, who plays the formidable Al-Sit; Haram Basher and Alsir Mahjoub, who play Nafisa’s parents; and Abdalla Jacknoon, who plays Babiker’s father, are all veteran stage actors who brought so much life and character to the story.

Overall, we were fortunate to receive the support of the Doha Film Institute, Highlight Productions, who worked on the film with their own crew and camera equipment, and On Set Team for Media Productions, who also came with their own crew and lighting equipment. We also benefitted greatly from the in-kind support of the Sudan Film Factory, who generously gave us audition and rehearsal spaces and became a hub from which we worked throughout the preproduction phase. I was also lucky to work with postproduction professionals who gave me hours of their time at film-loving prices, including editor Abdelrahim Kattab, sound designer Falah Hannoun, and colorist Walter Cavatoi.

How did making the film bring you closer to your roots? And what have you learned about Sudan while making the film?

It was a pleasure for me to reconnect with Sudan through cinema. Even though my family is scattered all over the world, it’s through them that I remain constantly connected to Sudan and the idea of home. I come from mixed Sudanese and Russian backgrounds, and it is through my parents, Mirghani and Olga, that I’m embedded in Sudanese stories, music, culture, and cuisine. My mother was a caregiver to my Sudanese grandparents and so she learnt how to speak old-fashioned Sudanese words that are barely used today, is immersed in the stories of the older generation, and is renowned for her “mullahs” (whenever I visit, she always gifts me a jar of “wekah”). I have three sisters, Nadia, Tatyana, and Julietta, all of whom lived in Sudan at different ages and create their own readings and feelings of home. We have built our own version of Sudan through our memories, relationships, and ideas of home.

We’ve recently been seeing the rise of Sudanese filmmaking and the success of Sudanese films. How does it feel to be part of that?

It was inspiring to watch incredibly brave pioneer filmmakers like Amjad Abu Alala, Marwa Zein, Hajooj Kuka, Suhaib Gasemelbari, Mia Bittar, Mo Kordofani, and Issraa El-Kogali make films in Sudan before the revolution. Now, it feels not only possible to do and say and create in Sudan, but necessary to express voices and opinions and stories that were suppressed or ignored for so long. I’m most interested in telling stories about women and girls who struggle for a more equitable Sudanese society. One of those avenues of creative self-expression is cinema, and I’m honoured to contribute to Sudan’s growing cinema scene.

You wear many hats, a writer, director, producer, researcher and filmmaker. What do you enjoy the most and why?

Writing, researching, directing, and producing are all part of the same long process of getting a film made. I enjoy each one of these activities as part of a whole, and I have learnt a great deal by always involving myself in my films at every stage of the production process.

I studied media and communications, and filmmaking was part of that process. I don’t separate my academic research from my filmmaking. For me, these are part of the same world. To be a filmmaker means that you are also necessarily a researcher, and I find that each role enriches the other and gives me better insight into the practice and politics of art. Since AL-SIT is so steeped in exploring social and familial relations as well as the history and politics of agriculture, I conduct a lot of research into the story of cotton and its British colonial institutions, out of personal interest but also as background for the film. I work for a research center and so I’m constantly inspired by our in-house academic explorations, and I try to take some of the broader macro questions and turn them into creative projects.

What’s next for Suzannah Mirghani?

AL-SIT was a “proof of concept” for my first feature called COTTON QUEEN, which explores more in-depth the themes I broach in the short. I completed the feature script in a Doha Film Institute Hezayah workshop; I presented it to industry professionals in a DFI Producers’ Lab; and I connected with producers during DFI’s Qumra 2021. I hope to gather funds and make the film within the next two years.

AL-SIT is currently at the beginning of a festival cycle, which last for approximately a year and a half. Mirghani has spent the last few months applying to film festivals all over the world. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most film festivals have either been canceled, or have taken place online or virtually. Nevertheless, the film has succeeded especially having qualified to enter the competition category for short films at the Academy Awards (Oscars). Mirghani hopes that AL-SIT can be released to online platforms for people to watch at home in Sudan.