Rebuilding Sudan: What You Need to Know

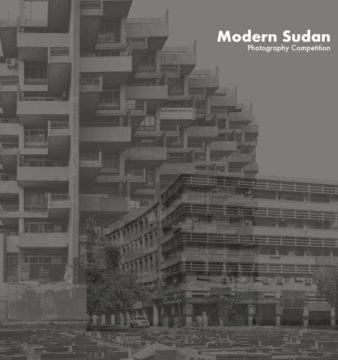

Khartoum Skyline. Image credit: © Qusai Akoud

Since 19 December 2018, protesters in Sudan have been chanting for freedom, peace and justice. The Sudanese people are calling for a revolution, and most importantly, for President Omar Al Bashir and his regime to step down. Sudan has long been a nation riddled with conflict and tension, and the people have had enough.

However, while the public is focused on regaining their rightful and basic human rights, the imperative topic of rebuilding the country’s infrastructure and economy remains. Sudan’s urban infrastructure is comparably more developed than other sub-Saharan African countries with only a few countries, particularly in the north, have improved their infrastructure over the past two decades.

In 2005, Khartoum was named the Arab Capital of Culture, an initiative undertaken by UNESCO, under the Cultural Capitals Program, to promote and celebrate Arab culture and encourage cooperation in the Arab region.

Recent economic history

The capital city of Khartoum covers an area of about 21.83 square kilometres with an estimated population of at least 7 million. Since South Sudan seceded in 2010 and took 75% of oil revenues, Sudan witnessed a large portion of delayed projects due to the resulting economic recession. Al Bashir’s government promised an emergency plan to revive economic investments and set off a boom in construction projects by the end of 2015.

The US sanctions, which were first imposed in 1993, have long been a major factor to the hindered development of the Sudanese economy. However in 2016, the Obama administration announced their desire to lift these sanctions with five conditions to be met in six months. Unfortunately, dreams to revive the economy were crushed when Sudan was hit with extreme inflation merely a month later.

Khartoum 2030

- Doxiadis and Abdelmoneim Mustafa 1991 Structure Plan Source: Hafazalla 2008: 48, Khartoum 2030

- McLean’s 1910 Plan of Khartoum showing highlighted areas where the plan was implemented; Source: McLean and Hunt 1911: 282, Khartoum 2030

- MEFIT and CENTECS 2008 Structure Plan. Source: Mefit and Centecs 2009-1:86, Khartoum 2030

“Khartoum 2030: Towards an Environmentally-Sensitive Vision for the Development of Greater Khartoum, Sudan” was published in The Journal of the Scientific Society Ludovico Quaroni, and is undoubtedly the most comprehensive vision of urban restoration and development created to date. It outlines visions and goals to be attained for a sustainable transformation of Khartoum.

Written by Dr Gamal Hamid and Dr Ibrahim Badreldin in 2014, “Khartoum 2030” compares a number of master plans proposed and implemented in Khartoum. A key finding in this summary notes, ‘Most of those plans… have paid attention to the urban environment in Greater Khartoum and included recommendations and projects to protect and enhance it. However, implementation has not been in par with the planning and programming mainly due to the lack of political will and consequently, meager budgetary allocations for this vital sector. It is hoped that this trend will be reversed soon and implementation of the planned interventions…receive the support and commitment they deserve.’

Greater Khartoum, which is formed by Khartoum, Omdurman and Khartoum North (Bahri), accommodates about 6% of the state of Khartoum’s total area, and is the most densely populated city in Sudan. A phenomenon dubbed as hyper-urbanisation, where the population increases exponentially, has been witnessed in Khartoum. This abnormal surge is attributed to ‘rural-to-urban migration’, namely by citizens seeking a better quality of life or escaping civil war and famine.

The issue of hyper-urbanisation is a global one, affecting many major cities around the world. However, there are serious risks in developing countries such as Sudan. John Scott, Head of Sustainability Risk at Zurich Insurance Group, said, ‘Rapidly increasing population density can create severe problems, especially if planning efforts are not sufficient to cope with the influx of new inhabitants. The result may, in extreme cases, be widespread poverty. Estimates suggest that 40% of the world’s urban expansion is taking place in slums, exacerbating socio-economic disparities and creating unsanitary conditions that facilitate the spread of disease.’

Comparisons between Khartoum’s different master and structure plans, Source: Khartoum 2030

Sudan’s unsustainable cities

Traffic congestion next to a market in Khartoum. Image credit: © Muhammed El Samani

A Twitter poll conducted by 500 Words Magazine found that a majority of users believe that the rest of Sudan’s major cities lack basic infrastructure and services. Twitter user Zainab Gaafar said, ‘They are equipped. The quality however, including Khartoum, is negotiable. To me, it’s a case of quality versus quantity.’

According to the 2008 census, Wad Madani ranks eighth on a list of Sudan’s top major cities. Rana Salah, an Architect at CTC group, whose family is from Wad Madani, states, ‘Madani doesn’t have the same level of services and infrastructure as Khartoum. Although it’s relatively calmer and cleaner than the capital, most of the locals have migrated to Greater Khartoum for convenience. The city now mostly consists of people who came from other towns in Gezira.’

Wad Madani’s migration situation could ring true for the rest of the cities throughout Sudan. In an interview with Rawan Kamal, PhD candidate in University College Dublin, she said, ‘Khartoum is considered the main hub for major government buildings, headquarters, industries and amenities. Historically, Khartoum welcomed piecemeal waves of urban immigration. Thus, planning efforts have been concentrated in Khartoum. However, all the cities call for attention in several areas in an urban level. These include infrastructure, road networks design, areas with a cultural and historic character, energy preservation, adequate open spaces and urban sustainability.’

In another poll, 85% answered that Khartoum completely lacked adequate roads and highway planning, drainage and sewage systems and public spaces. Most Sudanese are generally aware of the nation-wide infrastructure and planning dilemma. But as hyper-urbanisation continues to put pressure on the already poorly planned infrastructure, how can the seemingly never-ending cycle be broken?

Public participation

Drainage infrastructure for most of Khartoum. Image credit: © Muhammed El Samani

A 2013 research by Dr Ibrahim Bahreldin, outlines the significance of public participation in Sudanese planning initiatives. Public participation is a fundamental element to the inclusion of diverse needs and spaces for a growing population.

Mizah Rahman, co-founder of Participate in Design and contributor to the Global is Asian website, said, ‘Increasing accessibility of urban planning information allows for crowdsourcing of solutions. Making the design process more transparent by teaching citizens about urban planning [demystifies] very complex planning and architectural issues, thereby improving accessibility of information… [and] gives them the opportunity to put forth their own solutions to problems they have identified.’

Kamal also mentioned the differences in planning mandates between Europe and Sudan. ‘There are a number of planning models, for example in Europe, that encourage public participation and involvement. This is achieved by enabling the public from delivering their opinion about planning permissions and new developments. Local people are engaged in decisions related to planning through what is known as a notice period; a duration to protest against a certain development or construction activity,’ she said. ‘This is not the case in Sudan, where such a system is impermissible. A new platform and planning dynamic that engage the public in planning decisions and heritage preservation would strengthen the connection between people, the city and their heritage.’

Dr Bahreldin’s research, titled, “A Critical Evaluation of Public Participation in the Sudanese Planning Mandates“, offers suggestions to improve planning guidance in Sudan. Firstly, that planning mandates should encourage implementing public participation from an early stage of planning, such as plan development and decision-making.

Early participation is encouraged to prevent dilemmas that may otherwise arise post-approval or during implementation. ‘Land politics and ownership is usually a complex topic in developing countries, where geographical, political, economical and cultural layers play a role in land acquisition,’ explained Kamal. ‘Sudanese people are known for their strong ties with social traditions and culture. These linkages influence the local community’s acceptance for change and modifications. However, it is arguable that cultural and historic building preservation professionals could benefit from this in drafting national strategies. City planners should gradually pull the community into the reconstruction project of the city through awareness campaigns, transparency and local engagement. Compensations are to be provided when land is reclaimed for development purposes.’

The research also recommends that planning mandates should encourage the inclusion of diverse public participation techniques. Many tools have been developed around the world, such as an online interactive 3D modeling platform by MIT, which helps people visualise how the structures can be incorporated into a space.

Senior Assistant Director at the Centre for Livable Cities (CLC), Remy Guo, has noted how Seoul successfully increased public participation and knowledge development. Citizens and residents were offered a series of programmes dedicated to educating them on the planning process and further analyse their own neighborhoods. These training programmes taught them how to identify problems and solve them efficiently.

500 Words Magazine‘s Twitter polls found that 84% believe that it is both the public’s and government’s responsibility to adequately use and maintain public facilities. While 64% believe that there is a higher shortage of transportation infrastructure than provided modes of transportation.

The current atmosphere in Sudan will undeniably bring about a new wave of thought progression. For many, it represents a positive change in public stance and hope for the future. While many demand new leadership, the dilemma of a broken infrastructure and poor provision of service continues to be a burden. Amidst the unified voice of the Sudanese people, lies the solution.

Iman Taha is an architect residing in Dubai where she currently works for Jacobs, a global engineering company. She discovered her passion for design at a young age and it continues to inspire her daily work and writing. Her recent work with Remy Architects has led her to be part of the team for the 2018 award-winning residential project, KH Villa. Iman believes in preserving the environment through innovative architecture for a cleaner, sustainable future. She hopes to dedicate her career to raising awareness and developing projects with minimal to zero environmental impact. When she isn’t busy designing contemporary houses, she enjoys baking and hosting gatherings for friends and family. You can connect with Iman on LinkedIn.

Iman Taha is an architect residing in Dubai where she currently works for Jacobs, a global engineering company. She discovered her passion for design at a young age and it continues to inspire her daily work and writing. Her recent work with Remy Architects has led her to be part of the team for the 2018 award-winning residential project, KH Villa. Iman believes in preserving the environment through innovative architecture for a cleaner, sustainable future. She hopes to dedicate her career to raising awareness and developing projects with minimal to zero environmental impact. When she isn’t busy designing contemporary houses, she enjoys baking and hosting gatherings for friends and family. You can connect with Iman on LinkedIn.