The State of Urbanism and Architecture in Sudan

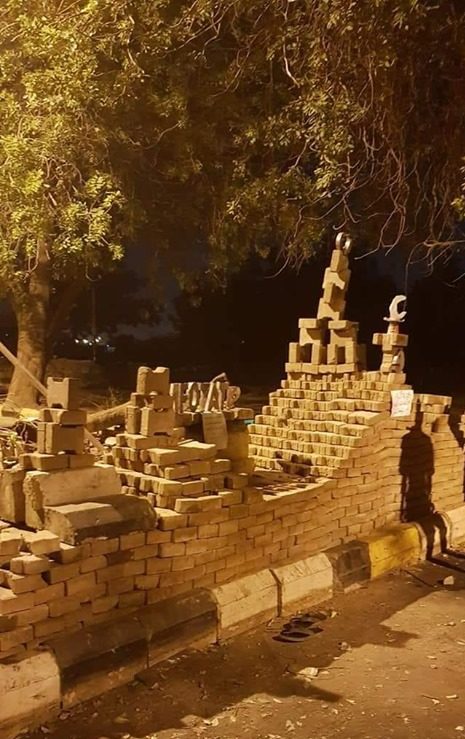

During the Sudanese revolution against political, economic and social state of the country, there was a parallel artistic revolution, in music and arts. The revolution manifested in new understanding of symbolisms, experimental ways of expression, and a collective community sense for what is perceived as “good” art. This was felt all around Sudan and specially at the sit-in in front the military headquarters in Khartoum.

The revolution did not impact the country’s architecture and urbanism, at least, not yet. Architecture, being the practice of designing space, and urbanism, being the architecture on the scale of neighbourhoods and cities, are practices that reflect the community and shape it at the same time, but it is also a collective culture that flourishes with experimentation and social feedback. The field is slow in showing noticeable development, because of the long design, construction process and the long years needed to understand the actual impact of a building or urban intervention in the society it serves.

The evolvement of urban and architectural scene is even slower in Sudan where the bases in theory and practice were never set before. The field suffered decades of deterioration, or more accurately, it never had the chance to progress.

The first main reason is continuous negligence from authorities by failing to provide adequate regulations and policies to govern built environment. Since it was never the interest of government, from the British rule onwards, to provide an urban life that caters for the people of Sudan nor to enhance the economy. The official interest has long been to benefit from the deterioration of urban life and maintain the streets as hostile environments to its users in order to ease control over the streets and in extension and over the public. Unused streets jeopardise the chance of communication and organisation within the public, and that situation appeals to authoritarian, corrupt governments in Sudan.

The role of governmental urban policies in disrupting peace in Sudan was highlighted in the article, Sudan Student Protests Show How Much City Planning and Design Matter, by Sudanese-South African architect and professor Amira Osman in 2016. According to the article, the authorities attitude in applying these policies and their persistence in excluding the citizens from decision making is a bigger trigger to public anger than the poor policies themselves.

The role of pedagogy

Another main actor in the ominous state of the field is the academic and intellectual contributors. The University of Khartoum (UofK) had one of the first architectural departments in Africa. It was founded in 1957 but failed to produce any actual contribution to the field. The department was part of Faculty of Engineering up to 2012, which shows the perception in Sudan of architecture and urbanism as technical field. There are now 24 architecture schools in Sudan, and all have failed to even document vernacular architecture and local urban patterns, let alone advocating for innovation.

The current curriculum teaches global history of modern architecture in a narrative that lacks depth and comparative analysis to local realities. While some Sudanese architects’ names are known to the students but none of their methodologies or theories are studied or analysed. This is a consequence of the poor documentation that is evident in all fields as a result of crippling policies in the country. But regarding the time extended time frame, negligence must be blamed when such institutes are still not able to address their own field in its own local environment even after many decades after establishment. This is a pattern of thought that started with the first head of the architecture department in UofK. British modernist architect, Alick Potter, did not appreciate local design methods and ignored it in his teaching and practice. The continuous negligence is seen in the design studio works that are produced and graded with disregard to both, theoretical background and practical construction cognisance.

In results of governmental and academic deficiency, there has been a negative impact on the culture. The Sudanese people have lost their connection with vernacular architectural and urban culture due to instable and political and economic strategies that were disruptive to human habitats which have been sustainable and evolving for centuries. On the other hand, the people didn’t have the chance to develop a new relationship with built environment because there hasn’t been any initiative from legislative bodies, academic institutes or practicing architects to build a positive relationship between the people and their habitat.

Current practices and the way to solutions

Recently there have been few initiatives that were met by public appreciation. For example, the design of affordable housing by Octantis Architects based on thermal comfort and local living spaces relations, or the recent proposal that aimed to reflect contemporary national history on a monumental structure bearing the names of martyrs of the revolution. On both scales, despite the genuine intentions, the designs displayed total indifference to the urban patterns, the effect of the buildings on street users and the local identity of built environment. While the public appreciation shows how the Sudanese people are sincerely interested in their built environment, it also shows their lack of tools to form an aware public opinion.

The current practice of architecture is used as a mere tool to provide shelter under a primitive understanding of space. Economic factors pushed architecture to be a fake luxury that uses cheap materials and technologies. The aesthetics are borrowed from plastic and trivial buildings of capitalistic cities, by replacing street facades with cladding screens and cityscape with isolated buildings that undermine both the street life and indoor comfort, while functioning as a face of a fake identity. Khartoum winds up with poor building quality and a socially troubled built environment. The faint trace of life in the street in Sudanese cities is a result of the masses of impoverished people who fight to keep the streets livable.

Well-designed built-environment can contribute to the quality of life by offering access, security and interactive social spaces. Khartoum is a great example of the disastrous implications of a poor built-environment. The city of Khartoum does not protect street users from lawless practices by authorities neither does it offer a space for healthy social or economic interactions specially for the working class. Vernacular methods have proved its workability in Khartoum in the latest public demand for civilian rule, as vernacular neighbourhoods offered social structures that unified its inhabitants, and layers of private and public shared spaces.

In these neighbourhoods, protests and social disobedience actions were harder to crackdown as seen in Banat, Atbara in comparison to Al Mohandiseen, Omdurman; Buri, Khartoum; Al Riyadh, Khartoum; and Al Taif, Khartoum. This rough display of the state of architecture and urbanism shows the importance of documentation and theoretical critical literature of current and vernacular practices.

The need to invest in built environment is amplified recently, as the obvious effect of hostile streets on the public ability to organise and mobilise to voice their demands for a better life. In light of the revolution, moving towards a government that meets the needs of the people, Sudan should rebuild its destroyed communities on solid bases, implementing policies and guidelines to involve the public in reshaping and reconstructing their built environment.

Misdar Alneel is a Sudanese architect, who studied architecture in Malaysia and Oman, and continued her post-grad education in Italy, Milano. Several of her built designs are in Oman and UAE. Misdar aims to practice and experiment with architecture by pursuing to define the Sudanese approaches to beauty, urbanism and human habitat.

this is a very rich content of information, i hope architecture in sudan walk with steady strides to create the

identity of the country in a unique artistic way that reflects sudan’s essence and personality.