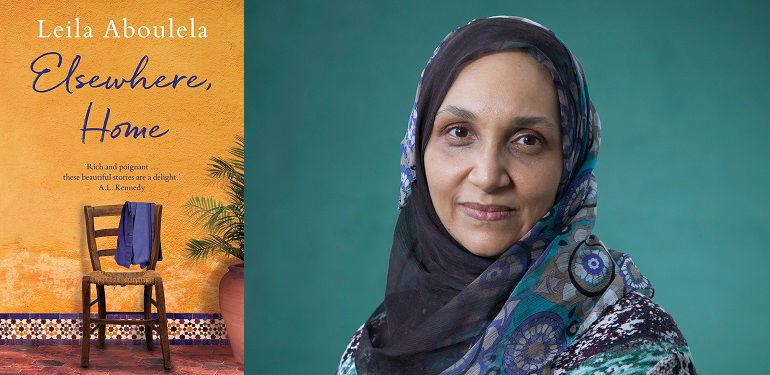

Book Review: ‘Elsewhere, Home’ by Leila Aboulela

Image source: The Book Banquet

‘I will always see the grass, patches of dry yellow, the rugs of palm fiber laid out. They curl at the edges, and when I put my forehead on the ground I can smell the grass underneath. Now that we have a break, we must hurry, for it is as if the birds have heard the azan and started to pray before us. I can hear their praises, see the branches bow down low to receive them, as they dart to the trees…If I was not praying, I would stand with my feet crunching the gravel stones and watch the straight lines, the men in front, and the colorful tobes behind. I would know that I was part of this harmony, that I needed no permission to belong. Here in London, the birds pray discreetly, and I pray alone,’ writes the award-winning Sudanese-Egyptian author Leila Aboulela in her latest book, Elsewhere, Home.

From the sun-kissed streets of Khartoum to the chilly streets of London, from the concrete spacious buildings in the Gulf to the packed apartments of Scotland, the small details of life in Elsewhere, Home illuminate larger truths which affect us all.

Elsewhere, Home was a gift from my mother, knowing that I was a huge fan of Aboulela, it was the first thing she bought once she landed in Heathrow. The book is a collection of short stories Aboulela has written and published over the last 20 years. Elsewhere, Home won the Saltire Society Fiction Book of the Year Award 2018.

With a collection of 13 intimate stories of longing and exile, the book offers a rich lesson on life as an immigrant abroad, as they carry the country they left and the country they currently live in, attempting to adapt whilst struggling to find some kind of meaning and sense of belonging.

These stories feel as if they are an autobiography of Aboulela herself and of all the people in the diaspora looking for a place where their identities – a clash of a gazillion cultures – can breathe, without feeling ashamed or isolated, in a sanctuary they can call home.

Living in a foreign country is not always sunshine and rainbows after all. You may leave your home but it will never leave you. It will forever be in your genes.

‘But she was not a tourist, and for her Egypt could never be a holiday destination like Jordan or Greece. Desert, pyramids and sphinx were embedded in her DNA,’ writes Aboulela in Elsewhere, Home.

These stories explore a disconnection between people across generations and their cultures. They are sensitive pieces that elegantly narrate how immigrants battle with their other identities.

‘Yet there remained within her a faint memory of a complete closeness with her mother, a time of unqualified approval that was somehow lost with her ability to speak her mother’s tongue’, writes Aboulela.

Aboulela beautifully explores the many ways in which our differences can merge to form a richer human experience and how the primitive human desire for love and friendship will always be a way of overcoming our sense of isolation, just as with Shadia and Bryan, the lead characters of Aboulela’s short story, The Museum (2000).

One narrative tells the story of a Sudanese woman, whose life has radically changed with marriage and pregnancy – the loss of her independence and status dominates.

The insecurities of the characters, their humbleness, tolerance and adaptation to very different cultures, and events was inspiring to me. The stories reminded me that we are all very much same, with our own secret everyday vulnerabilities, battles and victories.

The stories bloom as a series of episodes which condense the poignant journeys the immigrants are going through; introducing new characters; new situations.

A narrative tells the story of a woman who leaves Khartoum to live in Aberdeen to be with her Scottish husband, who loses the charm of being a white man in Africa.

‘The good looking khawageh, who had pursued and enchanted her in the Gezira Club, has whisked her off her feet and away from her family, had brought her to a drab life, in a drab place. In Scotland, he lost the charisma that Africa bestows on the white man,’ writes Aboulela.

Aboulela, seamlessly and elegantly writes scenes that made me stop and ponder on the sad circumstances of our country, a Sudan that crumbled after falling victim to our government.

‘If I find a way to live here forever,’ he says, if only I could get a work permit. I can’t imagine I could go back, back to the petrol queue, to computers that don’t have Electricity to work on or paper to print on. And a salary, a monthly salary that I less than what an unemployed person gets here in a week!

This book, has given me hope that there always is a way out of the dark, a belief that there certainly is nothing more resilient than the human spirit.

However, it broke my heart to learn of the many battles immigrants go through everyday, searching for ‘home’ elsewhere whether that be through love, friendship, making a family, going to the museum or even by simply imagining wrapping a tobe around your body.

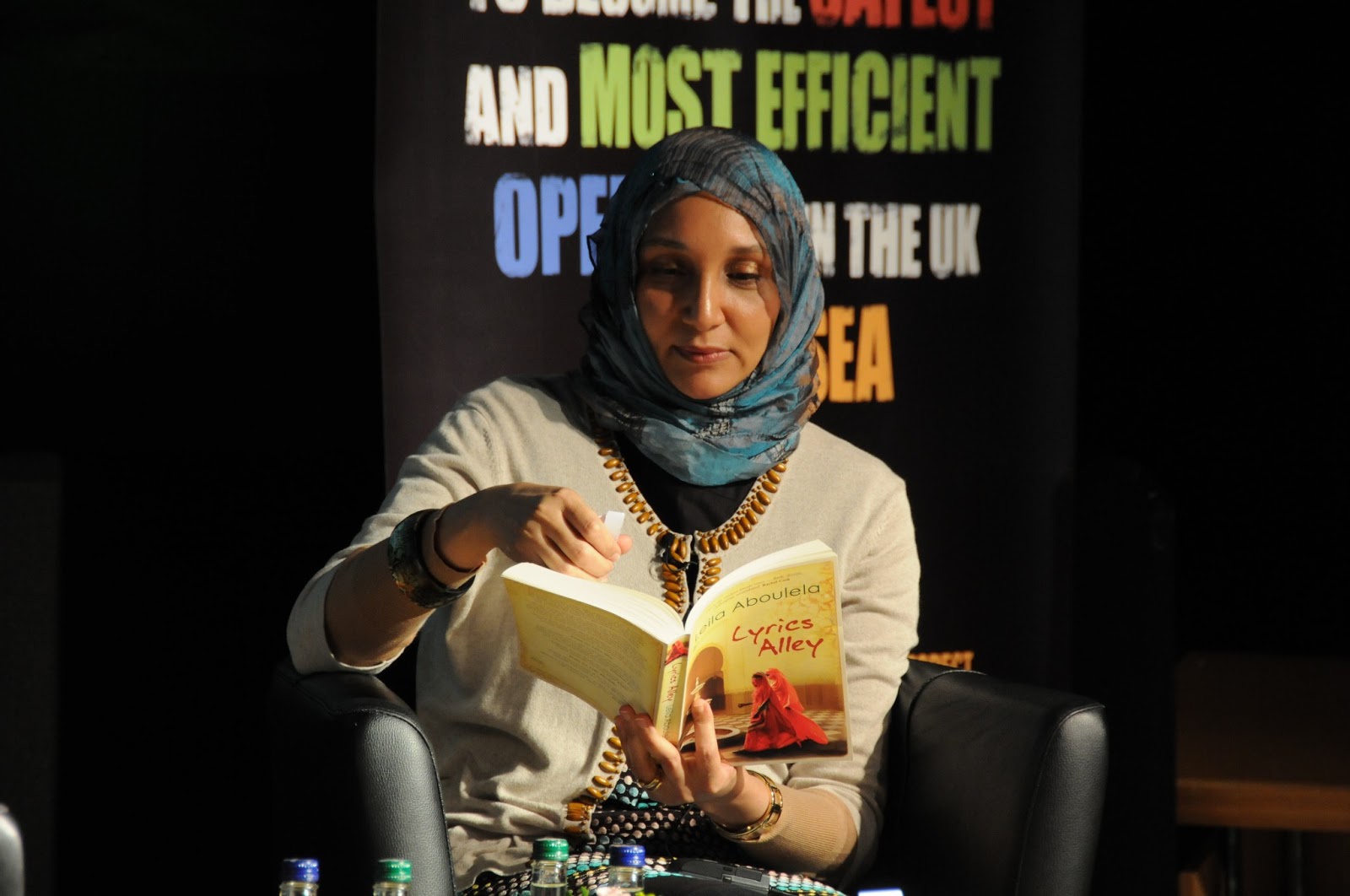

Image source: Caine Prize Blog

Elsewhere, Home is a must-read simply for the beauty of Aboulela’s writing.

Now living in Aberdeen, Aboulela’s work has received critical acclaim for her distinctive exploration of identity, migration and Islamic spirituality in her writing. Her novels were all long-listed for a Women’s Prize for Fiction (formerly known as the Orange Broadband Prize for Fiction), which is one of the UK’s most prestigious literary prizes, annually awarded to a female author of any nationality for the best original full-length novel written in English.

Rahba’s mother giving author Leila Aboulela a tour around British General Sir Herbert Kitchener’s room in the Medical Campus of the University of Khartoum

I first met Aboulela when I was eight years old when she came to Sudan for a visit in 2007. As my sisters talked about their experience transitioning from England to Sudan, I’ll never forget her elegance and humbleness as she listened attentively as we sat and drank tea together.

We were given a signed copy of Coloured Lights (2001) and Minaret (2005) afterwards. I would first read my favourite, Minaret, which follows the journey of Najwa, a young woman forced to flee her home in Sudan in the face of the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983 to 2005).

A book I would review at our school assembly, and still give out to my friends to read to this day is Lyrics Alley (2010). Translated into 14 languages, Lyrics Alley is a fictionalised account of the life of Sudanese poet Hassan Awad Aboulela. The book is a Fiction Winner of the Scottish Book Awards in 2010.

Another signed copy I happily received from the author is The Kindness of Enemies (2015) when she paid a visit to the University of Khartoum.

It was in Aboulela’s novels that I first felt the power and significance of representation. Representation matters.

Rahba El Amin is a fourth year medical student at the University of Khartoum, trying to do her little bits of good everywhere she goes. She is a blogger, book-worm, aspiring writer, photographer and human rights activist — who can’t live without shai bei laban.

Rahba El Amin is a fourth year medical student at the University of Khartoum, trying to do her little bits of good everywhere she goes. She is a blogger, book-worm, aspiring writer, photographer and human rights activist — who can’t live without shai bei laban.

RELATED LINKS:

Exclusive Interview | Leila Aboulela – Perspectives of a Literary Artist

Such a passionate review! Loved it😍

[…] http://500wordsmag.com/art-and-culture/books/book-review-elsewhere-home-by-leila-aboulela/ […]