It’s Time for Sudanese Literature to Believe in Sudan

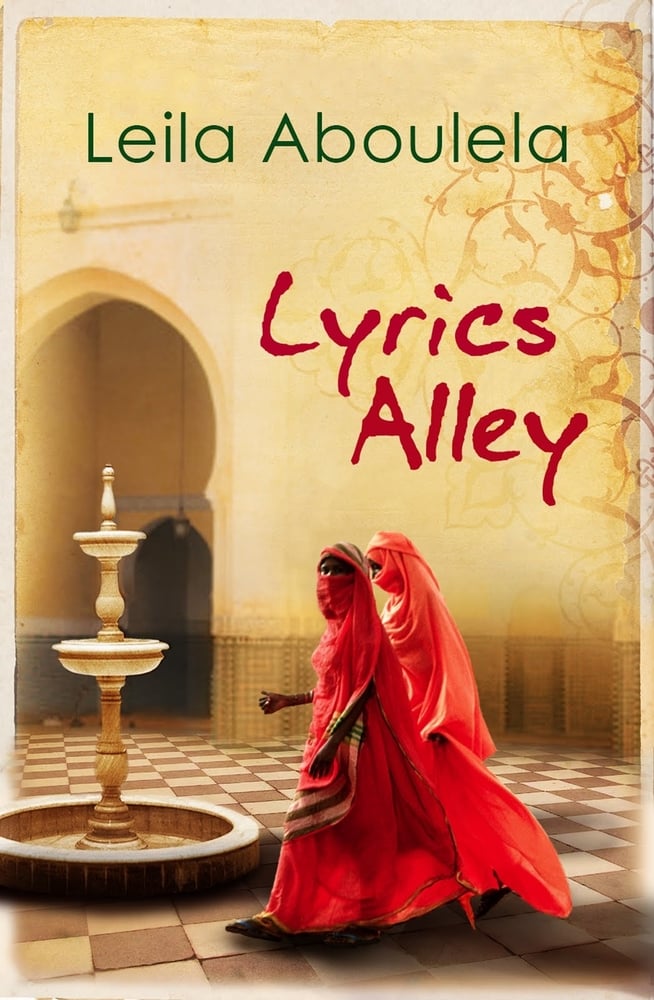

Hajja Waheeba, from Leila Aboulela’s Lyrics Alley, is a character well-known to anyone who has spent any time in Sudanese communities. A full-figured older woman, arms jangling with bangles, and cheeks marked with tribal scars, she is animated and driven by her love for her family. So why then, in a novel purportedly about Sudan, is this quintessential Sudanese woman the only character not given an inner life? Why is she the only character whose point of view is never explored?

I gulped down Aboulela’s Lyrics Alley in two days. At first, I was thrilled to see Sudanese characters and Sudanese society depicted in the pages of a novel – something I have not seen since reading Tayeb Salih. But then, as I continued through the story, I was reading quickly for another reason — surely, I kept asking myself, there would be a twist. Surely, this novel would not wholeheartedly and sincerely embrace the colonial narrative of a backwards Sudan, only enriched and modernised by Western forces?

Lyrics Alley is set in the 1950s, as Sudan prepares for and achieves independence. It is the saga of the wealthy Abuzeid family, based on the author’s own family history. The patriarch, Mahmoud Bey, has two wives: Hajja Waheeba, his cousin, and Nabilah, a young, Egyptian, “modern” woman. The story is told from the perspective of Mahmoud, Nabila, Nur (Mahmoud’s son with Waheeba), Soraya (Mahmoud’s niece and Nur’s fiancée), and Badr (an Egyptian teacher).

Despite these multiple perspectives, every character whose thoughts we are given, agrees that Sudan is a backwards country, and that the only hope for the country’s improvement is to receive enlightenment from England and the West, via Egypt. Even Nur, who occasionally pays lip service to surface-level Sudanese affectations such as loving the Nile River, is defined by the Western-style education he received in Egypt’s Victoria College. The racial politics are also not pretty — all of the point-of-view characters have significant Egyptian heritage to varying degrees. At no point in the story do any two fully Sudanese characters exchange a single word with one another.

I am not saying that it is wrong to portray characters who are interested in a Western education. I loved getting to know Soraya, whose thoughts are dominated by her love of Western fashion and her desire to cast off Sudanese traditions. I was interested too by Nabilah, her arrested development, and her unhealthy attachment to her mother. However, the loving depiction of these characters and their foibles, strengths and weaknesses, only highlighted to me the complete absence of Hajjah Waheeba’s thoughts and desires. It is as though the narrative is agreeing with the claim made by Nabilah, that Waheeba, because she is illiterate, is unintelligent and less capable of complex thought.

For example, let’s look at the exacting descriptions given of the various anecdotes Mahmoud Bey tells an English banker whom he wishes to impress. We are told in minute detail about which building Mahmoud describes and which young man’s background and heritage he lists. Through these conversations, we understand what is important to Mahmoud and why, as well as what he thinks might impress an Englishman.

On the other hand, when Nur is involved in an accident and spends time in the women’s hoshor courtyard, Hajjah Waheeba and the cousins who stay with her are described as spending their days entirely in preparing food, grooming and gossiping. Well, what are they gossiping about? Are they telling each other stories? Are they speculating about future marriages or divorces? Why is Mahmoud’s description of which Greek men own the most expensive villas in Khartoum important and worth reading about, but the specifics of Waheeba’s conversations are not? It is apparently enough to merely say they are gossiping, a frankly sexist dismissal of the world of women.

Waheeba is shown merely as an agent of irrationality and backwards thoughts. She speaks only of emotion and superstition and female circumcision – the very tradition used by colonialists, and later Western-educated Sudanese men to paint Sudanese women as stupid and unenlightened. She is a series of outbursts that are not even contextualised by interiority, and she is also a representation of all that is traditional in Sudan. All that does is confirm the harmful narrative that Sudan needed colonisation, and the intervention of Western education and beliefs, and in fact, that it still needs such intervention.

This attitude permeates the entire novel. It is encapsulated in the struggle of Badr, the Egyptian teacher, to move his family out of the traditional Sudanese-style home in which they live. From his very first chapter, he overhears Mahmoud Bey’s friends speaking about apartments: “The word ‘flat’ in a city where everyone lived in houses — villas for the rich and mud houses for the poor — rang in the room, distinctly Egyptian… Yet that word ‘flat’ was clear and right, a good place to live in, a proper home” (Aboulela 19). Essentially, we have the “flat” described as “unSudanese” and also, like everything not Sudanese in the novel, better and more proper. In Badr’s last chapter, he does move into a flat, and his progression up the stairs, called progress by the narrator, is painstakingly detailed. This right here is the colonial narrative in short — through great effort, colonial subjects can become more like colonial masters and that is both progress and unequivocally good. Note, as well, that this story is told from the perspective of the educated, literate Badr, and not his stay-at-home wife, despite the fact that the story she experiences in the background — slowly making friends with her Sudanese neighbors, dealing with untrue accusations from her senile father-in-law — is much more interesting than anything that happens to the teacher. Additionally, more time is spent on Badr’s climb up a set of stairs, than is spent on any “traditional” Sudanese character’s words, thoughts or beliefs.

I am troubled, too, by the fact that no one can solve problems in the story without appealing to either a Westerner or a Westernised Sudanese person. Soraya wants to study. However, her father, the only character other than Waheeba to be explicitly described as traditional, is both violent and not fully on board with women’s education. Of course, such men do exist and no doubt there were even more of them during the 1950s. What I take issue with is the fact that Soraya’s allies in her fight against her father are Sister Josephine, an Italian nun, and Mahmoud Bey, the most Westernised member of her family. Why not show it is possible for solutions to come from a Sudanese context?

I am thoroughly disappointed by this novel, especially when I compare it to others such as Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, which takes the time the explain indigenous Nigerian customs within the context in which they take place, managing to depict and explore the meanings of deplorable customs such as infanticide without excusing them.

The colonialist overtone is significant in Lyrics Alley. It is especially problematic because Aboulela is the most well-known Sudanese writer working in English, and a cursory glance at reviews for the novel reveal that for many, it is the first novel about Sudan that they have read and likely the only one they ever will read.

However, I have seen the same problem in other works of art created by Sudanese artists for international audiences. It is time for a Sudanese literary tradition to believe in Sudan. I want to experience Sudanese works of art that take Sudanese subjects seriously and do not rely on the intervention of Westerners or Western education as a means to save Sudan from itself. I want a work of art that thrums with pride for Sudan and can see both problems and solutions arising from a Sudanese context. I know that such proud Sudanese voices already exist, but they must be lifted up and highlighted, and ideally, translated into English so they can be read by both international audiences and Sudanese readers born in the diaspora. Those artists that do insist on casting Sudan as a place only of problems must be challenged. Because if we cannot, even in fiction, even in art, see ourselves as problem-solvers, what hope do we have in the real world?

Zeena Mubarak is a 24-year-old Sudanese American writer living in Germany. She is currently pursuing a Masters in English Literature and Culture at the University of Tuebingen.