The Stories Behind the Walls of Sudanese Homes

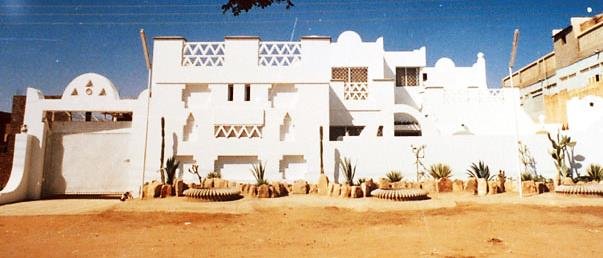

Typical villa in Khartoum. Image courtesy of Fatima Joda

Echoes of laughter and the smell of food fills the air with nostalgia. Thick brick walls provide shelter throughout the cold winters and heavy rains, while uniquely positioned vents bring in ample light to brighten our days. A sandstorm emerges, and the red-orange tinge washes the interior, issuing an amber warning to grab freshly hung laundry from the yard. These structures are our homes, with more than just stories to tell. They’re uniquely crafted by architects and experts with centuries’ worth of knowledge. Each region in the world is home to a type of vernacular architecture, shaped by location and history; and Sudan has a story of its own.

History and traditional housing

The history of Sudan begins long before the Arab conquest of Egypt and Syria, when Sudan was at the prehistoric age of 7000 BC. Tribes settled along the Nile with hunters and farmers, living in mud-brick houses built solely for shelter. The bricks were made of mud from the banks of the Nile River and solidified with straw. By 16th century BC, when the Kingdom of Kush was established, much of the architecture began to take a unique shape. Since then, many kingdoms fell and new ones emerged, simultaneously developing Sudan’s architecture.

The Kushite period saw the erection of different buildings, such as the Nubian pyramids in Meroë, as well as many palaces, temples and baths. All of these required a skilled workforce. Nubian architecture is known for its distinctive features which include vivid colours, geometric images carved in mud and white plaster, and wall-mounted objects as part of the interior, features that can still be seen today in some houses around Sudan and North Africa.

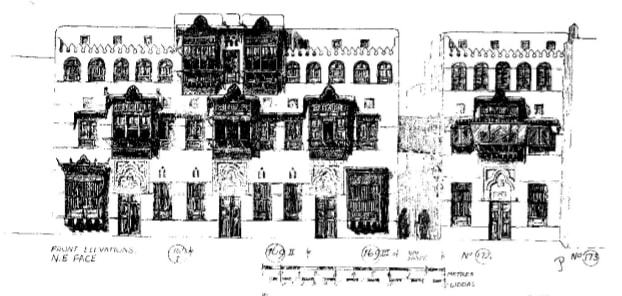

Shortly after Islam spread to Sudan, between the 16th and 20th centuries, the well-known Ottoman island of Suakin was built. Although, most of the town is now in ruins, photographs and what’s left of its buildings gives an insight to the style that developed in that era. The characteristics of the buildings in Suakin were greatly affected by coastal climate, and that prevalent architecture evolved throughout the coasts of the Red Sea.

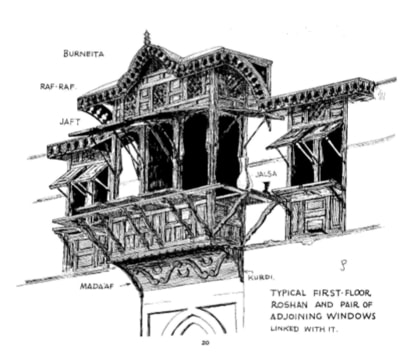

Mashrabiya design. Source: Greenlaw, Jean-Pierre. Coral Buildings of Suakin. Kegan Paul International, 1995.

In the book, The Coral Buildings of Suakin, written by Jean-Pierre Greenlaw, this style is described to be ‘one which will catch every available sea-breeze and allow it to circulate freely throughout the house… It consists of two or three-storey houses with vertical […] walls pierced by many-shuttered windows and characteristic mashrabiyas, large casement-windows projecting out into the street in order to catch the breeze.’ The houses in Suakin were well-ventilated and shaded. Built from corals, as many of the coastal cities, this material provided natural ventilation due to its porous characteristics. As Greenlaw adeptly mentions, it is ‘an aerated style’.

Delving into a traditional Suakin house and studying how the interior was designed to suit their daily needs, it is apparent that Islam was a guiding factor in their lifestyle. The houses were divided socially, into private and public spaces; unlike Western living, where functionality guides design. On the ground floor, space was reserved for reception and entertainment, while upper floors were for family. The living quarters, called harim, were divided into fully independent suites for each branch of the family. Extended family members lived in neighbouring houses, often building a house on the adjacent plot when the main house could no longer accommodate them, forming a ‘family neighbourhood-unit’.

Traditional Suakin Houses. Source: Greenlaw, Jean-Pierre. Coral Buildings of Suakin. Kegan Paul International, 1995.

Colonial architecture – the beginning of a transition

During the condominium period, Western architecture was introduced to Sudan. The early 20th century was a turning point for Sudan’s architecture and construction industry, and continued to prevail throughout the 1950s – 60s.

In his 2007 research article, Dr Fathi Bashier, Professor at Wollega University in Ethiopia, notes that ‘architects were fully aware of the climatic constraints as evident in the environmental design approach they developed.’ Once again, architects were guided by climate in their designs, ensuring that the buildings were adequately ventilated and shaded from the heat. However, in terms of space planning, that was not the case.

Gordon Palace, Khartoum

The first Governor-General of Sudan, Herbert Kitchener believed that the British architecture and space planning, that the new rulers were accustomed to, were more suitable to their requirements and overall function. This perspective was also evident in Khartoum’s town planning. The British employed their own engineers and essentially relied on Egyptian builders. Subsequently, the first master plan for Khartoum was prepared by W H Mclean, who was greatly inspired by the late English city planner Sir Ebenezer Howard OBE. Sir Howard conceptualised the ‘garden-city’ movement, an urban planning method in which self-contained communities are surrounded by greenbelts, which contain proportionate areas of residences and agriculture.

Towards the mid-20th century and the independence of Sudan, there was a noticeable shift in architectural style. Colonial authorities began training locals to assist the British experts, and eventually develop required skills and knowledge in construction. This period birthed the first generation of prominent, trail-blazing Sudanese architects.

Khartoum – an independent city

Ironically, although this period was pivotal for architects; political unrest and living conditions brought most developments to a standstill. The government prioritised the consolidation and unity of Sudan, neglecting work on infrastructure and built-environment.

- Perspective with “exploded” roof Source: Margret and Alick Potter © Margret and Alick Potter

- University of Khartoum Examination Hall; Source: Ministry of culture and Information © Ministry of Culture and Information

University of Khartoum’s Department of Architecture was established in 1957, becoming the regional nucleus of architectural education. The first head of the department, Professor Alick Potter, designed a variety of ancillary buildings for the university. Of his most notable projects is the main examination hall, which is aptly described in the book, Fundamentalists and Other Arab Modernisms, as ‘an outstanding architectural benchmark for generations to come’.

In 1958, when American aid programmes were initiated, the first private architectural consultancy in Khartoum was established. Headed by Austrian architect Peter Muller and Lebanese structural engineer Robert Ayoub, they designed a large portion of the aid projects. Some of these include the Sudan National Museum and the Bata Factory.

Throughout this time, most of the architecture in Sudan was produced by foreign architects. Nonetheless, the year 1962 marked a significant shift in the industry as a result of a massive demand for housing in the Khartoum extensions. British-educated Sudanese architect, Abdelmoneim Mustafa, dubbed as ‘The Godfather of Sudanese Architects’ due to his unique and original design approach, was among some of the architects that returned at the peak of the housing demand.

Age of modern architecture

‘Following the emergence of modern architecture and the common use of reinforced concrete as a building material, during the 1970s to the 1980s the trend shifted towards exposed structure. Architects Abdelmoneim Mustafa and Kamal Abbas utilised exposed beams and slabs to shade openings…floor plans were orthogonal and modular, guided by equally spaced column grid systems,’ said Dr Tallal Saeed, Head of the Department of Architectural Design at the University of Khartoum.

The pervasiveness of the ‘Modern Vernacular style’ marked the first phase of Sudanese modern architecture.

‘It produced a mixed style which [reflected] the adapted expressions of Modern European architecture, and the traditions of the colonial period environmental design approach,’ said Bashier. ‘It was replaced by the ‘Modern Mediterranean villa’, and finally the ‘Tropical Modernist’ style.’

- Khartoum Villa. Source: Abdelmoneim Mustafa Pamphlet

- Villa by Abdelmoneim Mustafa in Amarat, Khartoum. Source: Bashier, Fathi. (2007). Modern Architecture in Khartoum 1950-90

A perfect example of the latter style can be seen in the ‘Khartoum Villa’, designed by Abdelmoneim Mustafa. His design language was clearly depicted in this project through his use of exposed brick and cantilevered slabs. There is a clear connection between structure and environment, witnessed in his unique consideration for light and outdoor to indoor space transition, all whilst providing protection from heat and dust.

Integration of indoor to outdoor spaces in Abdelmoneim Mustafa’s villas. Source: Image courtesy of Eng. Hassan Mahmoud; CRITICAL REGIONALISM: STUDIES ON CONTEMPORARY RESIDENTIAL ARCHITECTURE OF KHARTOUM-SUDAN – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate.

The second phase was witnessed from the 1970s. A shift in design that was brought about by the increasing numbers of Sudanese living abroad, specifically in the Gulf region. Having experienced higher living standards, the style of this era reflected the lavish lifestyle of the new upper-middle class. The socioeconomic structure had undeniably transformed; specifically with the influx of oil-based revenues and signing of the 2005 South Sudan Peace Agreement.

According to Basheir, this transformation also resulted in ‘the decline of the Khartoum style and the rise of [globalised] fashions’, a phenomenon caused by exposure to global trends fuelled by new trade relations and cultural exchange. Basheir also mentions that the migration of the Sudanese drained the industry of unique expertise and young professionals who became more acquainted with the culture of globalisation, and as a result, a generation gap occurred. The industry however, became entirely Sudanese due to the development of the private sector.

A city in dilemma

Dar Mabruka by Jack Ishkanes. Source: jackishkanes.com

Today, homes all around Khartoum reflect different styles from Sudan’s historic periods. A combination of houses built between the 1950s to 1960s and a few new houses that mimic styles dating back to the Nubian period reflects the city’s style.

Dar Shummena by Jack Ishkanes. Source: jackishkanes.com

One of the architects that has predominantly used Nubian influence in his designs is Jack Ishkanes. Ishkanes’s imagery and designs are well-respected amongst the Sudanese architecture community. His concepts are based on his ‘search for a Sudanese identity in architecture’. However, there is a widespread concern amongst architects in Sudan that has plagued the industry for over a decade since the rise of the ‘globalised’ fashion.

‘Khartoum is now labelled an incomplete city. Most clients build for investment purposes. The result is a multi-phased project, due to lack of resources and Sudan’s unstable economy,’ said Dr Tallal. ‘There is a blatant disregard to regulations, not to mention the inexistence of building codes. Environmental approaches that were developed up until the 70s have been neglected following the dependence on air conditioning machines.’

It is possible that the rise of this epidemic is inversely relative to the economy’s deterioration in recent years.

Observing how spatial planning evolved, Dr Tallal also mentioned that houses designed during Abdelmoneim Mustafa’s era maintained outdoor terraces and front yards. In addition to their environmental benefits, they were crucial to the Sudanese social lifestyle. ‘Balconies have now reduced to a width of 1.8 metres and the popular 4 x 8 metre front yards are no longer considered,’ said Dr Tallal.

Vegetation in the Abashar Residence. Source: Image courtesy of Eng. Hassan Mahmoud; CRITICAL REGIONALISM: STUDIES ON CONTEMPORARY RESIDENTIAL ARCHITECTURE OF KHARTOUM-SUDAN – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate.

When questioned further, Dr Tallal reported that since about 90% of new projects are built for investment, a cycle of unruly trends has been observed. Most clients that require apartments above their residence, are only concerned with privacy and maximising profit. The result is a building that utilises the entire plot with no area to manipulate volumes and create dynamic facades. The lack of a diverse and regulated building material market is another complication. Most houses now resemble a large block with basic surface treatments such as cladding, Spanish tiles and paint.

Thus, the new generation of architects are limited by their surroundings for inspiration. Dr Tallal believes that the educational system doesn’t provide appropriate training to students or work on boosting morale. He also notes that the role of the architect still remains unknown to the Sudanese public.

‘They often request a copy of something they’ve seen built or designed, without realising that each house is uniquely built as a service, not as a mass-produced product,’ he said.

Many Sudanese homes still continue to revive a number distinctive features in space planning and design. Although, there is an absence of a truly unique ‘Sudanese residential architecture’, the works of renowned modern architects are focal landmarks that deserve recognition and protection by the Sudanese public.

Iman Taha is an architect residing in Dubai where she currently works for Jacobs, a global engineering company. She discovered her passion for design at a young age and it continues to inspire her daily work and writing. Her recent work with Remy Architects has led her to be part of the team for the 2018 award-winning residential project, KH Villa. Iman believes in preserving the environment through innovative architecture for a cleaner, sustainable future. She hopes to dedicate her career to raising awareness and developing projects with minimal to zero environmental impact. When she isn’t busy designing contemporary houses, she enjoys baking and hosting gatherings for friends and family. You can connect with Iman on LinkedIn.

Iman Taha is an architect residing in Dubai where she currently works for Jacobs, a global engineering company. She discovered her passion for design at a young age and it continues to inspire her daily work and writing. Her recent work with Remy Architects has led her to be part of the team for the 2018 award-winning residential project, KH Villa. Iman believes in preserving the environment through innovative architecture for a cleaner, sustainable future. She hopes to dedicate her career to raising awareness and developing projects with minimal to zero environmental impact. When she isn’t busy designing contemporary houses, she enjoys baking and hosting gatherings for friends and family. You can connect with Iman on LinkedIn.