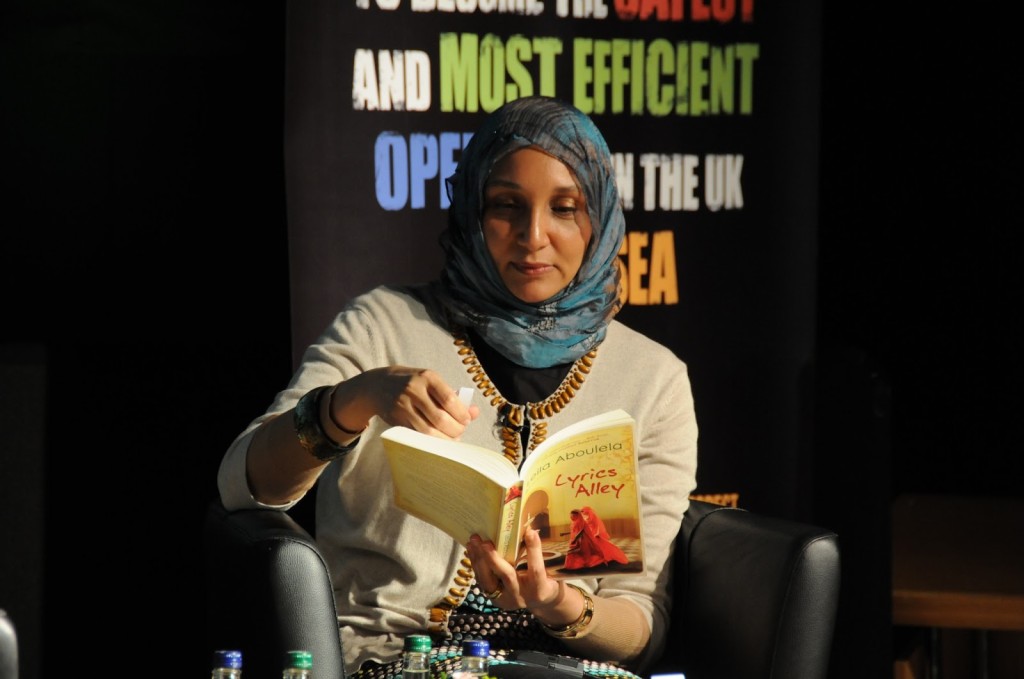

Exclusive Interview | Leila Aboulela – Perspectives of a Literary Artist

500 Words Magazine got the chance to catch up with Leila Aboulela for an exclusive interview about her novels, writing and life in Sudan. The interview was compiled by Fatima Sulieman and Leena Al-Samani for 500 Words Magazine.

Leila Aboulela’s latest novel Lyrics Alley was Fiction Winner of the Scottish Book Awards and short-listed for the Commonwealth Writers Prize. It was long-listed for the Orange Prize as were her previous novels The Translator (a New York Times 100 Notable Books of the Year) and Minaret. Her play The Insider, in which she re-imagines the lives of the unnamed Arab characters of The Outsider, was recently broadcast by BBC Radio to mark the centenary of Albert Camus. Leila is a recipient of the Caine Prize for African Writing and her work has been translated into 14 languages. She grew up in Khartoum and now lives in Aberdeen, Scotland.

500 Words Magazine: Apparently writers hate this question, but we’re going to ask it anyway. Why did you decide to become a writer?

Leila: In my mid-twenties I reached across-roads in my life. I wasn’t able to complete my Statistics PhD and I found myself living in Scotland with little chance of returning to Sudan. Most of the day I was stuck at home with my young children and (in those pre-internet days) there were very limited opportunities for me to meet or interact with like-minded people. I started to write as a hobby. Reading had always been an important part of my life and writing felt like a natural extension. I joined an evening Creative Writing class and found welcome and support. Gradually, as my work started to get published, I began to think of myself as a writer.

500: You grew up in 1970’s and 1980’s Sudan, which you’ve portrayed in a positive light in your article “The unconventional city” how do you see Sudan now? And how much has the Sudan you grew up in influenced your writing?

L: What children see, hear and experience sears itself into their psyche. My memories of the Sudan of my childhood are vivid and it was homesickness which made me want to hold on to these images and put them down into words. When I returned to Sudan after being away, I continued to look for what was familiar and it was still there, in patches, among the modernity and changes that had taken place over time. Although Khartoum is not as cosmopolitan as I remember it to be, there have been many positive changes. The most important one being that there are more women in education and more women visible in public life.

500: It is common belief that art and literature reflect the realities and political and social nature of the time in which they were conceived. Do you think, judging from your novels, that modern day Sudanese society is an amalgamation of nostalgia and exile?

L: In the 80s and 90s, Sudan witnessed a significant incidence of brain drain. Many university graduates left the country to work either in the Gulf or Europe, the US and Canada. I belong to this generation and I remember clearly that we did not hesitate in leaving. We did not doubt that it was the right thing to do and that we ‘deserved’ the kind of life and jobs that suited our qualifications. The effect of this exile on our mental health, on family ties and on the identity of our children were things that were not considered, or at least, brushed aside. What our ‘hosts’ thought of our culture and the pressures to assimilate were also overlooked. Fiction gave me the space to explore these issues, to reflect on the impact of this movement. Modern day Sudanese society is defined by who left and who didn’t leave, who returned and who didn’t. Add to it the internal movement of those displaced by the civil wars and the Southerners leaving to South Sudan after the secession – and you get a repeated sense of a tearing away and a scramble to fit in which, on failure, morphs into nostalgia.

500: We want to talk about Lyrics Alley. Your descriptive style of writing, particularly in the way you describe Wahiba’s Housh, is awe-inspiring. Also, the characters in the book seem to accurately reflect the nature of Sudanese society in the 1950’s in the different classes, beliefs and lifestyles. How did you manage that, given that you haven’t witnessed it firsthand?

L: I spent a considerable time researching the period by reading books (in English and Arabic) and talking to elderly family members. This turned out to be fairly easy as I was writing about a recent past rather than, say, another century. My intention was to capture my father’s childhood and youth and so I relied on his memories and perspective. I also gained a lot by looking at old photographs. Throughout the time I was writing the novel I restricted my entertainment to only watching films and reading books that my characters would have been exposed to in the 1950s.

500: Lyrics Alley has triggered mixed emotions among your readership. Some found it very sad; others thought it was very positive because of its portrayal of Sudan – particularly Khartoum – in the 1950’s. How do you perceive the book? Do you think it’s sad, or hopeful?

L: The story of a promising young man’s life veering suddenly into severe disability is extremely sad. I was often crying as I was writing it. But I also found great pleasure in living through the optimism of 1950s Sudan and in engaging with the different characters. The character of the tutor Badr was the one I felt closest to and, ultimately, he was the one who was the most hopeful.

500: There’s a recurring character in your novels; the Sudanese girl moving to the West. Do you draw from your personal experience when writing? And if so, is it always beneficial or can it sometimes prove to be cumbersome?

L: It is not loyalty that continues to make me write about the movement to the West, it is deep fascination. Every writer needs to follow their obsessions but of course there are ways of avoiding repetition in order to produce a fresh piece of work.

500: The characters in Lyrics Alley, The Translator and Minaret are mainly based around Sudanese characters. Are all your novels going to be about Sudan or Sudanese characters? Do you have any works in the pipeline?

L: The novel I am writing at the moment has Russian characters as well as a Russian-Sudanese main character.

500: The Sudanese of this generation feel that Sudanese fiction written in English lacks a representation of today’s Sudan. We know this isn’t the Sudan you grew up in; however, you must have your own perspective. Do you see yourself potentially writing about the present through your eyes and in your niche area of Islam, love and immigration?

L: My novel-in-progress has a couple of chapters set in a present-day Khartoum complete with internet access and stylish coffee shops.

500: And finally, how many sugars do you take with your tea? We’re trying to find out how Sudanese you are.

L: Zero sugar with my tea. So I am as much Sudanese as those Sudanese who are watching their weight!

I love this.