Hala Al Karib: The Voice of Marginalised Women in Sudan

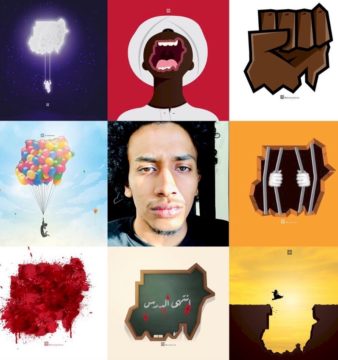

One of the leading figures of women activism in Sudan is Hala Al Karib, a Sudanese activist for women’s rights in Sudan and the Horn of Africa, and the Regional Director of the Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa (SIHA).

Born and raised in Sudan, Hala currently lives and works in Uganda, directing SIHA. Established in 1995, SIHA is a coalition of women’s rights activists with the aim of strengthening the capacities of women’s rights organisations and addressing women’s rights and violence against women and girls in the Horn of Africa.

Hala has also lived and worked in Canada, South Sudan, Kenya, Egypt and other countries in Africa for more than 20 years. As a civil society worker/activist, and social and gender research practitioner, Hala’s work focuses on women and girl’s rights activism and movements as well as refugees and displaced persons and minority community’s issues. Her educational background is in human rights, women studies and psychology.

In addition to her work as the Regional Director of SIHA Network, she worked for various international and regional organisations/institutions such as The College of Social & Economic Studies, Research Assistant at Juba University in South Sudan; Assistant Researcher at the sociology department at the American University in Cairo; Program Director at the Immigrant Women of Saskatchewan Inc in Canada and more. She has also worked as a consultant with various international and UN humanitarian organisations, including Goal Ireland, World University Services, Accord International and Concern International.

Hala’s activism is versatile. She also regularly writes about social injustice and the plight of Sudanese women for several international news organisations such as Al Jazeera, Foreign Policy (FP), openDemocracy, The East African and more. She is the Editorial head of SIHA Journal – Women in Islam in the Horn of Africa (Arabic & English).

500 Words Magazines speaks to Hala Al Karib about SIHA, her activism, and women’s rights and challenges in Sudan.

Tell us about SIHA and how it was established.

A group of women rights activists from the Horn of Africa met in the World Conference on Women in 1995 in Beijing and felt that the Horn of Africa – the issues and challenges of women – is not really being represented or talked about. They felt they were sort of alienated. Within the MENA region, they come as second or third class in priority. With East Africa, they are not quite part of the eastern Africa region. So they decided, as we are a massive population and there are a lot of political changes that’s happening, why not have a regional network or coalition of women activist from the Horn of Africa? At that time, the region was problematic. Eritrea gained independence. The Ethiopian regime has changed adopting a multi-party democratic system. The South Sudan People Liberation Army (SPLA) began to have a voice in the South. Somaliland has become a semi-independent of greater Somalia and recognised by Ethiopia. Overall, it was an era of transition or this how it felt.

The founder of SIHA is from Somalia. Her name is Hibaaq Osman, who now runs Karama in the Middle East.

How did you become affiliated with SIHA?

Ahfad University for Women (AUW) offered SIHA a space within the university. Then I came across SIHA at Ahfad. I was doing freelance consulting. At that time, I was in Canada and had just returned in 2004/5. Initially, I was told that they need someone to do part-time work with. So, I started to do part-time. And that worked for me at that point of time. Eventually I really liked it. I liked the idea of working for an indigenous women rights African civil society. I started to really get along well with the board of directors – the Somali landers, Asmahan Abdusalam, Ethiopians and South Sudanese. I developed strong relation with Dr. Sidiga Washi, a professer of family science at Ahfad and was serving as the Chair of SIHA at the time – and I really enjoyed the environment of solidarity. After that, I began to dedicate more time for SIHA. Eventually, after a year, we grew and left Ahfad and had our own office, but still kept our regional secretary in Sudan. We began to work on sexual and gender based violence (SGBV) protection programmes. We began to integrate Sudan’s legal framework. There weren’t many voices in SGBV from Sudan. We setup programmes in Darfur and became very close to survivors of sexual violence. From 2005-8, until the indictment of Al Bashir, we did a lot of work in Darfur with survivors of sexual violence. We began to work very closely with marginalised communities in Khartoum as well. It was a tough period, but it was also a learning curve for SIHA and its focus, and even for our relationship with the grassroots.

As of 2008, after the indictment of Al Bashir, we were documenting and working with sexual violence cases in Darfur. As the NCP government was targeting groups that work to address human rights violations, our work was largely affected. We had to literally work underground and take serious precautionssince we were under surveillance. At the same time, SIHA board was banned form entering Sudan to have a regional meeting. The board made a decision that we cannot have a Sudan regional secretariat anymore. So, we relocated our regional/head office to Uganda. During that period, every day, our office would be wrecked by NISS. I was surprised why they never shut us down. They were horrendous, dark days. After the indictment of Al Bashir, the government became paranoid and they were profiling civil society. We maintained the office in Sudan, which was and continues to be our biggest operation, and despite the critical times, our work in Sudan was growing. I was able to move away from the office in Sudan, which saved the office because at that time, my profile was very high so when I moved away, they backed off a little.

Now, SIHA has more than 55 staff members with 26 in Sudan with an office in Darfur and Khartoum. We are membership-based focused on grassroots.

You returned to Sudan from Canada in 2004/5. What made you decide to return Sudan?

I always wanted to serve. I’ve been an activist ever since I was a young student. It has always been my passion. I wanted to grow professionally in Sudan. I knew exactly what I wanted to do.

Prior to working for NGOs, in Canada, I was working in a refugee agency. I always worked with communities. I worked with migrant women who came from different parts of the world. I always did community work and community mobilisation. I came to Sudan because I wanted to be recognised and I wanted to see the value of my work.

‘The value of the work you do is different when you do something simple in Sudan for your people. You can’t imagine the difference it makes. You can work a lot aboard and you love it but the value of what you do for your people can make you highly psychologically-balanced, because it is your home.’

I’ve always been a feminist but my feminism is associated with or triggered by my desire for social injustice. I’ve always been intrigued by the polarisation Sudanese society within. It’s quite meaningless – how we discriminate against, abuse and undermine each other. It was very difficult to understand how can we be feminists and pro-women rights, and don’t really interrogate power relations within our society. It’s a chronic problem with many factions of women movements, which I feel is an extension to patriarchal structure.

Tell us about SIHA’s work in Sudan.

We are working on access to justice, which we are very focused on. There has to be fundamental change in the laws of Sudan so women and all those in the community who are marginalised can live in peace in society – but women in particular.

‘Sudan has one of the worst laws in the world. The country, that has these women participating in the great revolution, has one of the worst legal frameworks in the world. We have one of the worst family laws in the world.’

Child marriage is still encouraged as of the age of 10. Our family law is built on the idea of *qiwamah and *wilayah. The Sudanese society has overcome many things but the law is there and it’s the law that always defeats women. In Sudan, women cannot marry on their own even at court. They need a *wali who must be a male. Women cannot produce a birth certificate for their children without a male guardian. Imagine we live in a country with a big percentage of millions of women who head households without husbands – divorced or widowed – so they are really suffering to be able, for example, to get formal papers for their children. This is one the things that has very high discrimination against women.

Marriage and divorce in Sudan – it’s basically a system built for men to benefit while women are completely subjugated. It’s as if women are not full human beings. Then you find there is no enforcement of laws of the *nafaqah. Divorce is very complicated and it’s not documented. The man can divorce a woman in a minute, but if a woman wants a divorce, that could take her years.

Sudan doesn’t have any mechanisms of laws or policies to address domestic violence. All of our universities and offices do not have policies to address sexual harassment. Our criminal law, to today, criminalises a woman if she gets pregnant [illegitimately] and accuse her of *zina. And until 2015, the punishment of zina is stoning to death. Then they changed the law to change the punishment to hanging. Zina is quite a big issue and the difference is vague between zina and rape. That’s why the persecution of women of rape specifically adult women above 15 years of age is considered zina, minimal. Women of rape are afraid of being persecuted. In addition, the police don’t acknowledge rape – they immediately assume she’s a woman who committed zina. We did research called ‘It’s Always Her Fault’ about sexual violence in Sudan about two years ago. One of the interviews is of a woman in her early 40s. She was raped by the son of her neighbour. Her husband wasn’t around, working in the Gulf. She was in shock and went to the police to report it then the police asked her, ‘How old are you?’ She said, ’42’. He told her, ‘You are 42 years old and consider yourself raped? Get out of here!’

I went with survivors of violence in Darfur, the police laughed at us. They harass and intimidate us. It’s very difficult. These are all examples of the fact that we’re living under very miserable laws. We have one of the highest percentages of incarceration of women based on moral judgements.

‘We are a country where sexual violence exists. It’s not new. It didn’t begin in Darfur. Sexual violence has always existed. Women have always been raped in the modern history of Sudan from the time of Al Mahdiya. There were women who were raped in wars and in normal circumstances. We are a country that has a high percentage of marital rape. People think it’s normal. Even “consensual”, they cannot define it. ‘

Unfortunately, in Sudan, until now, our governments resist to give women their rights. The number of women who participated in the protests surprised everyone in the world. We have history of women movements that goes way back. But unfortunately, our government until now don’t see us as a priority. If it’s a priority, they would have done something.

How has COVID-19 impacted SIHA?

The pandemic impacted the communities we work with. It’s heartbreaking. Women lost a lot. They work today, they eat today. That’s it. They work day by day. If they had a little capital, it’s all gone with the lockdown.

The government is very shaky, unclear and messy. These people had a complimentary response to the COVID-19 crisis. Their emergency committee is so messy. The complimentary response brings the ministers and factions of the government together, and they sit and talk to people and communicate their plan to people. That’s how it is. But that never happened. In Sudan, we have places without troupes for at least three quarters of the people to wash their hands.

COVID-19 has exposed this government. The prevalence of sexual violence, domestic violence – they have nothing to respond to. But they could have responded to the economic crisis and the dire situations happening within communities in the peripheries of Khartoum effectively. They could have responded to the increased domestic violence, which appeared during COVID-19 – severe domestic violence, severe sexual violence. Women have nowhere to go. Where would they go? There is no police and there are no courts. Even if there were police, what would they do?

There is a woman who was cut by a sword. The husband hit her and their son. They survived.This is one extreme story of many. We have many cases of girls whose brothers are trying to hang them. We have cases of family members abusing little girls. And where to go? Today, for example, if they created policies that said, we acknowledge domestic violence is a crime and brought change to the law, then we can easily mobilise funds. There are lots of groups that give us funds and we can create a shelter. But right now, we can’t create a shelter. How can we do a shelter with the current laws? This shelter can be wrecked by police and further traumatise these women. There is no law to protect them. The situation is very dire.

What’s your take on Sudan’s current state?

The core issue is if we really want a civilian-run country in Sudan, there is no escape besides we make fundamental reform to our laws and policies, and move towards equal citizenship. There’s no other way around that. We have to have laws that would guarantee the human rights of everyone in Sudan including the poor, marginalised groups in conflict zones.

The elite Sudanese need to understand and give away a little bit of their privilege and share it with others if they really want a peaceful Sudan. But if they continue to be arrogant and disregard others, we will end up with a country that’s further completely disintegrated. There might not be a Sudan at all.

We have to be able to acknowledge our historic grievances that happened to people in Sudan and be able share with the historically alienated societies. We have to be able to meaningfully engage with them and grant them their rights. These are the principles of a civilian country – if you want a civilian state. Otherwise, it’s going to be a catastrophe.

SIHA offers various internships and volunteer programmes in Sudan and the Horn of Africa. To apply for an internship or a volunteer programme, or to support SIHA, visit sihanet.org. Find SIHA on Twitter @Sihanet, Facebook and Instagram @sihanetwork. Find Hala Al Karib on Twitter @Halayalkarib.

*Qiwamah, which generally denotes a husband’s authority over his wife, and *wilayah, which refers to the right and duty of male family members to exercise guardianship over female members.

*Wali is a male guardian. Wilaya (guardianship) in marriage is believe to be a kind of protection instituted by Islamic law to secure the interest of a woman’s rights.

*Nafaqah is the Islamic legal term for the financial support a husband must provide for his wife during marriage and for a time after divorce.

*Zina isan Islamic legal term referring to unlawful sexual intercourse. Sexual intercourse outside of marriage is forbidden in Islam. Adultery also constitutes as Zina.