Reminiscing About Sudan in Movies: Lost Past, Misunderstood Present and Perplexing Future

‘There are, it is clear, many Sudans, both real and imaginary – and many more possible Sudans. No account of these myriad visions of the country can be definitive,’ says a quote from The Sudan Handbook, a book that covers Sudan, South Sudan and the North-South borderlands through a set of essays written and edited by outstanding Sudanese and South Sudanese scholars and recognised international experts.

They say good art mesmerises you, but great one makes you think, and that implies perfectly to films and movies too.

My family moved to Khartoum, Sudan in 2014, two years later, I followed them. Ten years later, the country finds itself in the midst of war that has left 11 million people displaced, and 150,000 people dead. Now, Sudan is the ‘worst humanitarian nightmares in recent history‘, and the world’s largest displacement crisis, according to the UN.

At the end of December 2023, Al Gezira State became the latest target for the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) after war broke out in Khartoum in 15 April 2023 between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF. In February, Sudan went through a complete communications blackout for almost two weeks. In my town, and other towns and states in the country, it lasted longer – to this day. Internet is accessed only through StarLink, a satellite internet constellation operated by Starlink Services, an international telecommunications provider owned by American aerospace company, SpaceX. It was daunting to be left with uncertainty on many levels: the lack of information, isolation, unsafe transportation, gunfire and theft.

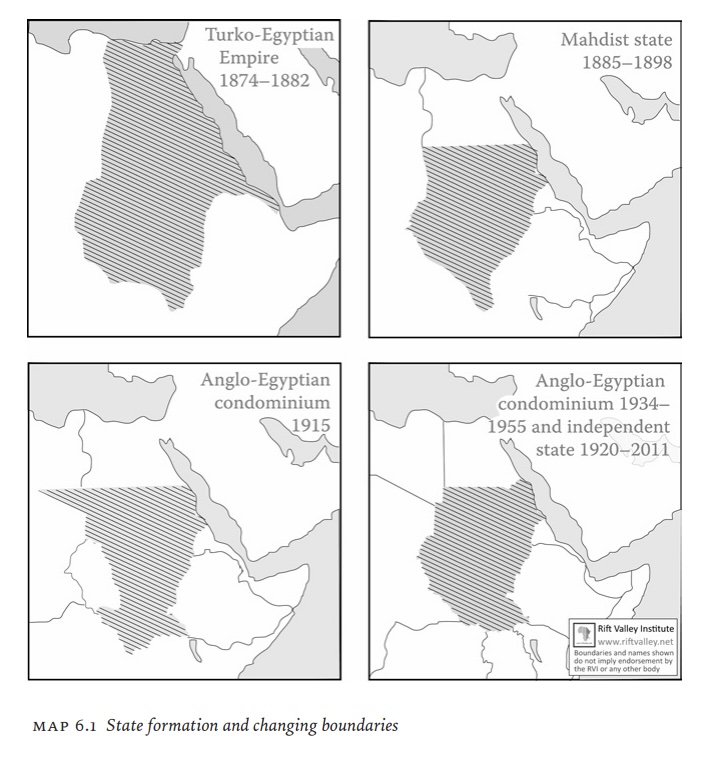

Repetitive episodes of Sudan’s history

Sudan, ever since its independence in 1956, has been in a repetitive loop. The length of each loop and the scope of events that took place vary, but in general, it goes as follows: new leadership and government, military coup, public revolution, transitional government, and it all repeats again. In many cases, although it is believed that an elected democratic government has taken place in Sudan, that step has always been purposely omitted by a history of dictators. Many scholars argue that since 1956, Sudan had almost a total of decade of peace and relative stability. However, most of Sudan’s recent generations have seen several governments rise and fall. Some regimes lasted longer than others such as that of Gaaffer Nimeiri (1971 to 1985: a 16-year-long regime) and Omar Al Bashir (1993–2019: a 30-year-long regime), leaving deep and long-lasting influence and weight on Sudanese lives and memories. Many believed that Sudan’s issue is absence of one national identity, thus several regimes tried to enforce one, that what reached its climax with the Salvation revolution, another name of Al Bashir’s 1989 coup that worked to enforce new national identity, an Islamic identity, to unify Sudanese wit the help of the late politician, scholar and islamist Hassan Al Turabi. Yet, such attempts led to further civil conflicts and discrimination within Sudan, including in Darfur and southern Sudan, which in 2011, separated to form the world’s youngest nation, South Sudan. That praise of an ideal culture, identity and people – what and who are Sudanese – was clearly noticed in television, advertisements, commercials, billboards and other forms of media.

The movies

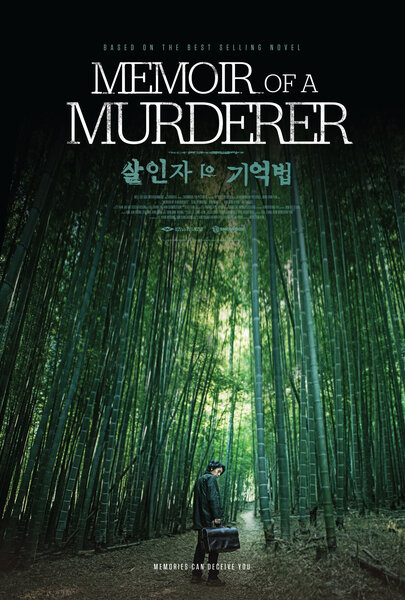

When fighting first broke out the SAF and the RSF in April 2023, we were still in Sudan, hoping it was just temporary. One of our neighbours shared with us random movies he had. I was convinced it would be better to stay awake and watch them at night as a way to keep myself awake and distracted from the sounds of gunfire and attempts of theft that commonly took place until dawn. Such experiences left me with vivid memories and many questions about news reports on Sudan from early 2010 and events I witnessed in past years. Later, all the memories and unanswered questions began to link and make sense. Two of the movies my neighbour lent us resonated with me: Recalled (2021) and Memoir of A Murderer (2017).

Recalled is a Korean thriller directed and written by You-min Seo. The mystery thriller film is about Soo Jin who lost her memory due to an accident. She keeps mixing her scattered memories and hallucinations with reality, until she remembers who tried to take her life.

Memoir of A Murderer is a Korean novel-based thriller directed by Won Shin-yeon and written by Jo-yun Hwang and Kim Young-ha. The mystery thriller film about Byung-su, an elderly man and former serial killer who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. As reality gets mixed with his memories of his days as a serial killer, he fights to protect his daughter from her psychotic boyfriend, who he suspects is also a serial killer.

The common thing between these two movies – and in Korean philosophy, in general – is the manifestation of how lost one can be if they lose their past. If you do not know your past, you misunderstand and misinterpret your present, and thus, have a perplexed future. And this can be true for both people and nations.

How many Sudans do we have?

Radical, tragic and unexpected events have the power to either be constructive or destructive. Such questions arise in the midst of the ongoing war in Sudan, alongside other questions: why 15 April, how did we get here, and was it inevitable or stoppable? The formation of Sudan itself was influenced by many factors. The map of Sudan has changed significantly throughout the history. Even today, Halaib, a Red Sea port and town, located in the Halaib Triangle, is a 20,580 sq m area disputed between Egypt and Sudan. Thus, looking at it as independent catastrophe is impossible. It is like carrying a piece of a puzzle, trying to guess its place in a large jigsaw puzzle.

What I find interesting in the perplexing history of Sudan is that it resembles the puzzling state of memory loss as reflected in Recalled and Memoir of a Murderer movies. It is how the main characters who both suffered from memory loss were easily manipulated and misguided by external factors, and as they started to remember, that state of knowing made them less vulnerable and gave them more control and true sense to build upon their actions. This is the exact same thing when it comes to the influence of political instability which Sudan has suffered since its independence, a sentiment Sudanese as a collective share. Successive regimes, which have mostly been military, controlled every aspect of life especially media from newspapers to radio to TV shows to music, almost everything, to promote only one narrative, theirs. These narratives served many functions: to mislead public, and highlight or shadow events, creating a society that does not share a common collective memory with a gap between generations, how they lived, witnessed experiences and events whether it’s South Sudan’s civil wars (1963-1972 and 1983-2005), the Darfur conflict (2003), forced migration of people in Halfa and Manaseer in 1964 as part of the New Halfa Irrigation Rehabilitation Project, the killing of protesters in Al Qiyada in 2019, and in addition to the violence committed against civilians in countless protests and coup-related events such as illegal arrests and torture, theft, rape, murder and other crimes.

Conceptualisation of what is happening or has happened in any point of Sudan’s history seemed to be always an issue. But to be fair, for preceding generations and before social media, it was hard to hear about narratives other than that of the government. After the revolution in 2019 that Al Bashir, many things began to be documented and revealed as people shared their stories on social media while others made public interviews, documentaries and films.

As The Sudan Handbook states, ‘Sudan, it may be argued, has no single history; it has multiple histories, a clamour of competing versions of what matters about the past. The diversity within Sudan consists not just of the great plenitude of communities, languages, belief systems and ways of life that it contains. It also includes a radical diversity in ideas about what Sudan is that are entertained by members of these communities. Different histories, and different ways of understanding the relation of particular communities to the centres of power and to the governments that have tried to assert control over them – these histories are playing a key role in the current transformation of the Sudanese state.’ That is why it is important to tell stories; document history by all means and forms, through arts, researches, articles, interviews, documentaries, and films; remember to make voices heard; avoid domination and enforcement of narratives; know what happened and who we are; and avoid repeating history and the circle of lost past, misunderstood present and perplexed future.

Hadeel Mamoun Abdalla Nour is a 25-year-old Sudanese writer, editor and researcher based in Sudan. She graduated with a Bachelor of Science Honours in chemical engineering from University of Khartoum in 2023. With her interests in engineering, energy, sustainability, films, storytelling, and photography, she presents – since 2019 – content in English and Arabic in various magazines and social media platforms. Social media: X @HMAY99, Instagram @haddoola_m, Facebook facebook.com/Hamoun69, LinkedIn linkedin.com/in/hadeel-mamoun