The Human Cost of Sudan’s Public Health State of Emergency

On 16 March 2020, the Sovereign Council officially declared a public health state of emergency in an effort to contain the outbreak of COVID-19 in Sudan.

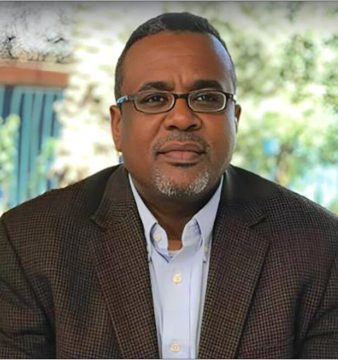

The decision saw the country undergo a significant power shift, essentially laying all decision-making rights squarely at the feet of the Minister of Health, Dr Akram Al Toum. Arguably the first competent minister of health Sudan had seen in decades, he enjoyed the nation’s unwavering support. An intelligent and qualified man, with a matter-of-factness and honesty about him, he inspired people’s trust and seemed the perfect candidate to guide the country out of crisis.

Many swift changes came about with the introduction of the state of emergency, of them being that an open budget was allocated to the health sector in order to support hospitals financially, logistically and with human resources as the need arose. It also meant the recruitment of military and regular armed forces in implementing the lockdown – guarding state lines, bridges and patrolling streets after curfew became their duty.

However, a more unpopular policy was the halting of all elective care and the shutdown of a significant number of hospitals with some set to exclusively receive COVID-19 patients whilst others were simply too unprepared to deal with the unprecedented gravity of the crisis.

As focus was shifted toward the viral outbreak, accident and emergency departments closed their doors to the public one by one, in turn shining light on the very human collateral damage caused by the state of emergency.

The number of Sudanese living with chronic illnesses is remarkable. Hypertension, diabetes and heart disease are rampant, leaving almost no household untouched. The last WHO figures from 2002 placed deaths related to chronic disease at 143,000. Outdated as the study is, one can assume that eighteen years later with an overall worsened quality of life and the deteriorated state of the healthcare system, these numbers must now be exponentially higher.

As of late, social media platforms have become flooded with queries as to where an operating hospital can be found to take a desperately sick loved one. Becoming an almost daily occurrence, these posts are often followed up by another plea – this time asking for prayers for their deceased.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the death toll caused by the virus extends far beyond the walls of COVID-19 wards. The fact of the matter is that other diseases did not conveniently disappear to make way for COVID-19 and neither did accidents. Vulnerable patients are still in as much need of life-saving medical care during this time as they were at any other and it is their lives that are inadvertently being paid as the price in the battle against coronavirus.

Two months on, the support Al Toum had at the onset of the crisis has waned among health workers and civilians alike. His most recent press conferences saw him lose his hopeful temperament, as it became apparent that things were not going according to plan. Overwhelmed beyond its capacity, the ministry of health has reached breaking point, eliciting an ever-increasing onslaught of criticism.

Al Toum now has the unenviable task of weighing the potential losses. Difficult as it may be, it is vital that the minister reconsider his policies as it seems Sudan may very well be on track to lose more lives in the way of lack of hospitalisation for chronic conditions than from those due to COVID-19.

Khansa Al-Bashier is a young Sudanese writer with an interest in all things literature, history and religion. When not writing, she can be found pursuing her education as a medical student.