When Cousins Marry: Sudan’s Genetic Challenge

A bride and groom at their jertik wedding ceremony. Image source: © Ola Diab

My parent’s homeland faces numerous challenges on its long road to becoming a well-functioning democratic society. Attention is rightly paid to issues such as ethnic disunity, weak institutions, egregious poverty, as well as the crumbling economy and infrastructure. But one issue that does not receive the attention it is due, is the widespread nature of cousin marriage in Sudan, more specifically the genetic and societal consequences it creates.

Historically, consanguineous marriages were prevalent throughout the world. Even in the west, until very recently, it was not associated with the stigma it is today. Many will be surprised to learn that both Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein married their first cousins in 1839 and 1919 respectively. It was not until the mid-19th century that a notable change in the attitudes of westerners towards consanguineous marriages began to occur.

Albert Einstein with his first cousin and wife Elsa Einstein

In the 1870s, American anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan was writing about ‘the advantages of marriages between unrelated persons,’ advocating that people should shy away from ‘the evils of consanguineous marriage.’ In 1846, a commission under Massachusetts governor George N Briggs studied mentally handicapped people and implicated cousin marriage as responsible for what was then termed ‘idiocy.’ A report from The Kentucky Deaf and Dumb Asylum found that cousin marriage ‘sometimes resulted in blindness, deafness and idiocy.’ And maybe the most decisive report at the time by physician Samuel Merrifield Bemiss concluded that ‘cousin inbreeding does lead to the physical and mental deprivation of the offspring.’ In recent times, more studies have been conducted which have further implicated cousin marriages in a variety of negative health outcomes.

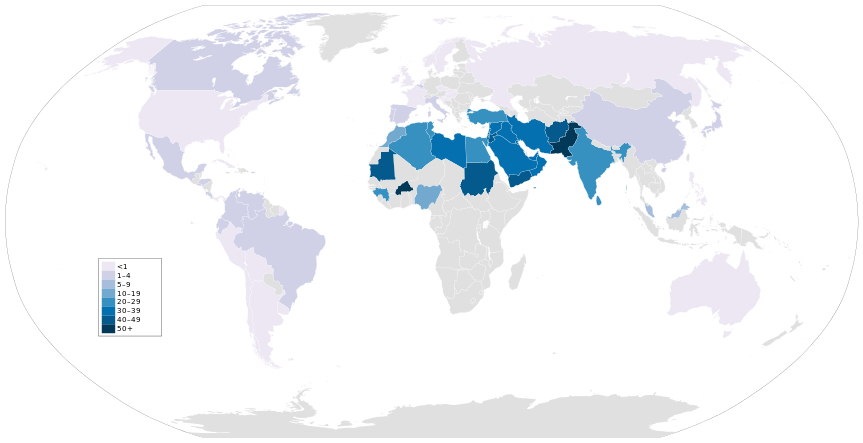

Studies conducted on the British-Pakistani community, among whom 50-75% of all marriages are between first cousins, found that though they only make up 3.4% of all births in the UK, they account for 30% of children born with recessive gene disorders. This is worrying for Sudan, which has one of the highest rates of cousin marriage in the world.

Another effect of cousin marriage that has been well documented in several populations is an intelligence quotient (IQ) depression in the offspring. Studies have put the number somewhere between a 2.5 to 10 average IQ point decrease. The significance of IQ depression should not be diminished. IQ has been shown to be positively correlated with academic performance, educational attainment, job performance, income and creativity. Given the high rate of cousin marriage in Sudan, it is reasonable to assume that the IQ depression is closer to 10 points than 2.5, which if true, will have resulted in the loss of hundreds of millions of IQ points across the nation.

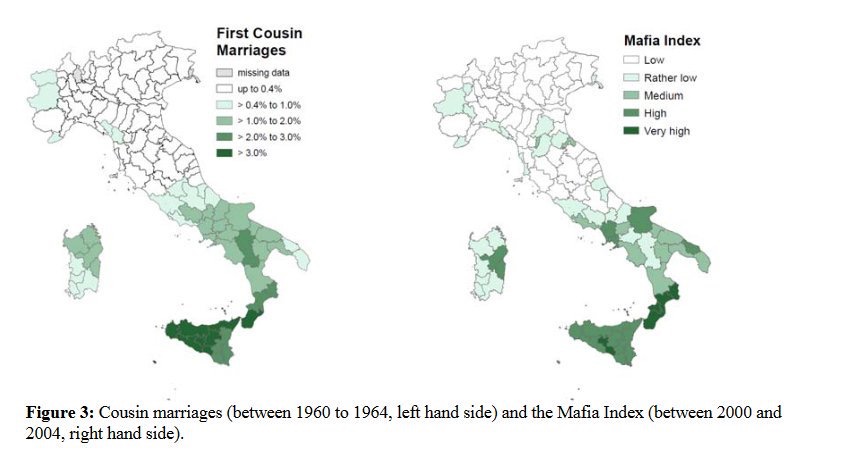

Map of the rate of cousin marriages in Italy between 1960-1964, as well as map of The Italian Mafia Index 2000-2004

Aside from the genetic consequences, there are also societal and governmental ones. Italy illustrates this clearly for us. Even though the formal institutions at the national level are the same, local government has been found to be much weaker in the southern parts of the nation where cousin marriage is common, than in the northern parts where the practice is very rare. The southern parts of the country are also where the mafia is strongest. It seems to be the case that the high rate of cousin marriage helps maintain the clan structure the mafia benefits from, which simultaneously damages the legitimacy of Italian institutions in those same parts of the country.

Critics of those who worry out loud about the rate consanguineous marriages will often say that the risks have been overblown, and are in fact very small. These objections accomplish nothing other than muddying the water. Yes, it is true that in isolation the health risks of cousins reproducing are relatively small. Cousins after all only share around 12.5% of their genes on average. However, societies that practice cousin marriage are likely to have been doing that for generations, meaning there is recent history of genetically similar ancestors reproducing. The reality is that upon examination, cousins in these societies often do not share 12.5% of their DNA, it is frequently significantly higher.

Critics of those who worry out loud about the rate consanguineous marriages will often say that the risks have been overblown, and are in fact very small. These objections accomplish nothing other than muddying the water. Yes, it is true that in isolation the health risks of cousins reproducing are relatively small. Cousins after all only share around 12.5% of their genes on average. However, societies that practice cousin marriage are likely to have been doing that for generations, meaning there is recent history of genetically similar ancestors reproducing. The reality is that upon examination, cousins in these societies often do not share 12.5% of their DNA, it is frequently significantly higher.

One example which illustrates the point is the phenomena of double cousins. Say two sisters meet two brothers, they pair up and both couples produce one child each. The two resulting children would be double cousins and would share around 25% of their genes, not 12.5%. That is equal to the percentage of genes shared by two half siblings, or a grandparent and grandchild. If those two children chose to reproduce with one another, the risks would be objectionably high. Add to that a generational history of consanguineous marriage, coupled with a small enough gene pool and you could find cousins sharing closer to 50% of their genes than 12.5%. This guarantees an increase in what geneticists call recessive conditions, meaning conditions caused by inheriting two copies of a gene, one from each parent, with each gene carrying a mutation.

This is a reality the Sudanese community, both in Sudan and abroad, has to accept and grapple with. It will require a huge cultural change in a nation where the practice is common and socially accepted. Studies have put the rate of first and second cousin marriage in Sudan between 40-49% of all marriages.

A systematic acceptance of cousin marriage is likely to have taken place in Sudan as a by-product of Islamisation occurring together with Arabisation. Islamic scripture permits cousin marriage, and Prophet Muhammed himself married his first cousin.

Regarding the prospect of future opposition from the religious establishment, there is however reason for cautious optimism. Currently, two of the four Sunni madhhabs (schools of thought) do consider cousin marriage Makruh (disliked). There are also three hadiths (record of the traditions or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad), which favour marriage outside of the family, although all three are considered ḍaʿīf (weak). Scholars like Ibn Qudamah and Al-Ghazali prefer marriage outside the family, arguing that if a divorce between related spouses were to occur, this would weaken the family bond which is sacred in Islam.

Map of the rate of cousin marriages by country in percentage

There are several Muslim countries that do not have an abnormally high rate of consanguineous marriages such as Indonesia, Bosnia and Kazakhstan. These countries are also alike in that they were Islamised but not Arabised. The high rate of cousin marriage in the Arab world appears to have preceded the advent of Islam, then spread as they conquered lands, built settlements and converted the indigenous populations. Among Jews in Israel for example, the highest rate of cousin marriage was found among Iraqi Jews (28.7%).

Whatever factor, or combination of factors that allowed consanguineous marriage to gain social legitimacy in Sudan, the current status quo just has to be broken. A damaging and divisive clan structure is being reinforced at the cost of already fragile institutions, while simultaneously impeding GDP growth and economic dynamism. Most tragically, there is a tremendous cost incurred by an inadequate healthcare system, along with needless misery being inflicted upon children who are born with completely avoidable afflictions.

Image source: Kurious/PixaBay

First and foremost a change in the mindset of the Sudanese people has to occur for there to also be a change in the culture. In the service of this cultural change, upper-class and upper middle-class Sudanese people will serve a crucial role. It is disappointing to note that in Sudan, unlike many other parts of the world, cousin marriage is not just highly prevalent among the poor, it could in fact be even more common among the wealthier. Had it been restricted to the uneducated, one can be forgiven for recommending education as the be-all and end-all solution. But while education certainly would help, it is only one of many measures that need to be taken. The people who are fortunate enough to have been sufficiently educated, who have the power to influence the culture and platform needed to change minds, have to take the lead. A change in culture among the most privileged is likely to trickle down to their less fortunate countrymen.

I am not opposed to a future ban on the practice of cousin marriage, but unaccompanied by any other actions, I am under no illusions about its potential efficacy. Even where it is outlawed today, agents of the government do not barge into the homes of unsuspecting cousin-couples, dragging them away to prison, kicking and screaming. The government simply refuses to recognise the marriage. Given the current state of Sudan and the character of the people who run it, I feel comfortable in asserting that a great many people across the nation could not care less about what the government does or does not recognise, thus making it an insufficient deterrent even if a law were to be passed tomorrow. If and when a law is to be introduced, the Republic of Tajikistan could serve as inspiration. The central Asian nation, which is 98% Muslim, banned the practice in 2016.

The price paid for marrying your cousin in Sudan must above all else be a social price. What is today socially approved and even encouraged has to become frowned upon, those who decide that their cousin and spouse will be one in the same will have to deviate from the norms of their society. For that reality to materialise, millions of conversations will have to take place. Everywhere from private homes, to elementary schools, universities and governmental institutions, to remote villages populated by the nations most disadvantaged citizens, people have to be made aware of the risks they are taking and engage in discourse with the people in their lives. Those who resist change, using religion, culture or tradition as argument, must be continuously challenged on their recklessness.

Mustafa Fagog Badri was born in Sweden to a Sudanese father and a South Sudanese/Italian mother. He is currently studying political science at Lund University in Sweden. He is politically right-of-centre and takes particular interest in issues such as economic freedom, secularism and animal rights.