Modesty in Sudan | Part I: Crack the Dress Code

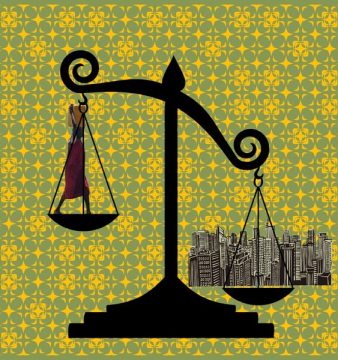

As Sudan embarks on a new era after the 2019 revolution, the country is embarking on a journey of reform. The youth, which has led the revolution, are asking questions about the current practices in all aspects of Sudanese life. Since the revolution, the conservative Sudan has witnessed various changes, one of which impacts the concept of modesty, which now has different interpretations. This will be explored in a series called ‘Modesty in Sudan’.

In this first article of the series, journalist Sara Gabralla is shedding light on the understanding and practice of modesty in Sudan. How has it evolved? And how has the community formed the dress code and why?

The definition of modesty

The word ‘modesty’ is linguistically defined as a ‘behaviour, manner, or appearance intended to avoid impropriety or indecency’. This is a generic definition of modesty which most religions and cultures will likely agree on.

When asked for their opinions on modesty in Sudan, Sudanese women, who are mostly subjected to dressing modestly, shared their opinions based on what they normally see on a daily basis in the community, specifically in the capital city, Khartoum.

According to Nuha Khattab, a teacher in Sudan, there are different kinds of modesty in Khartoum. They vary from complete hijabis or niqabis, where you can only see their faces and hands. Then there are modest girls who are not fully committed to the hijab, but wear modest clothes that are suitable for the public eye in Sudan. Lastly, there are ones who are liberal and westernised in their apparels, which has increased ever since the revolution, she said.

There are several factors to why we see all these kinds of attires and each believe that they are modest. These factors revolve around; firstly, religion; secondly, tradition; and lastly, the tool that had abused the previous two, which is politics.

Fundamental facts

To have a better understanding of Sudan’s community, it is important to understand a few fundamentals. First, Sudan consists of more than 95% Muslims, according to World Atlas.

According to the CIA World Factbook, in the Afro-Arab Sudan, almost 70% of the population believe that they are Arabs who live in an African country. This shows that the country’s ingrained beliefs and culture are derived from Islamic-Arab roots, which highly influences how modesty is understood and practiced across the country.

Perspectives on Shari’a Law

According to the Islamic Shari’a Law, modesty is strictly defined within the Islamic jurisprudence, which is known as Fiqh. Sheikh Adel Mohammed Al Tayeb, Imam and Scholar at Al Noor Mosque in Khartoum, defined modesty as:

‘A true modest Muslim woman should wear something that covers her entire body except the face and the hands. The clothes should be loose, cover her body curves and should not be transparent and flashy. The outfit should not bring any sort of disrespectful attention to the woman.’

‘If the women’s clothes do not meet all these conditions, then her hijab defeats the actual purpose…The main objective of the hijab is to avoid seduction or temptation, also known in the Islamic jurisprudence as the term Fitna,’ he added.

In addition, there is another factor that has spread the emphasis on the importance of modesty as stated in the Shari’a Law. According to Dr Yassir Yousef, an oncologist and writer, believes that the Wahabi and Salafi schools have had an impact on the religious views of the country. “Around the 70’s, a huge population of Sudan immigrated to the GCC, and mostly Saudi Arabia. When they resigned and went back to Sudan, they were culturally and religiously influenced by Saudi Arabia and had a lot of conservative ideologies – mainly following the Wahabi and Salafi schools,’ he said.

Dr Yousef thinks that this had or still has a huge influence on the transformation of the Sudanese community to become a much more conservative one. He described it as part of ‘The Islamic Revival’, which began to take place from the 1980s and thinks that it had a greater impact on conservatism in Sudan than the National Congress Party (NCP) did in 1989.

Commented on the religious aspect in Sudan, well-known Sudanese artists and political cartoonist, Khalid Albaih, said, ‘I believe that Sufism has a big role to play when it comes to modesty in Sudan.’ This is why Albaih believes there are different forms and beliefs of how modesty is viewed in Sudan. Sufism, which is also known as tasawwuf, is a form of Islamic mysticism that emphasises introspection and spiritual closeness with God.

According to American Islamic scholar Sheikh Hamza Yusuf, Sufism, in its different practices, revolves around the concept of ‘sincere inner directness to God’. This practice is more focused on spirituality while Sunni Islam mainly revolves around the practices and rulings of the Shari’a Law, which comprise of the Quran, the Prophet’s sayings and actions, and the rulings of the scholars or Ulama. Therefore, sometimes, there is a debate in Sufism on whether women’s hijab is a religious obligation or not, as opposed to Sunni Islam.

Culture and traditions

According to AtlasCorps.org, Arab culture creates almost 40% of the tribal composition in Sudan, while the remaining 60% are divided between African, Nubian and other origins.

In the paper, The Concept of Nudity and Modesty in Arab-Islamic Culture, Professor Marwan Al Absi said, ‘The Arab culture perceives the human body as something exclusively intimate’. He also stresses on the sensitivity of the female body as it is considered ‘a symbol of privacy, female dignity and honour in the Arab culture’.

The Sudanese Arab culture along with the Islamic Shari’a Law have formed the cornerstone of how modesty is perceived. The Arab culture is also a patriarchal one, which has had a tremendous impact on how modesty is practiced and applied.

Ameera Obaid, a housewife in Sudan, thinks that many women and girls in Sudan today, mainly in cities outside of Khartoum, dress modestly mostly because they are closely watched by their family members as well as those in the neighbourhood. She said, ‘I’ve seen so many girls wear the headscarf or dress in a decent way just to avoid the nagging of their male family members. Yet, deep down, they do not want to dress like that.’

Sometimes, the Sudanese culture has an opposing view of how modesty should be practiced especially in rural areas. Dr Yousef said:

‘I think the societal approach to modesty between rural areas in Sudan and the big cities like Khartoum and Wad Madani is completely different. In rural Sudan, if we are talking particularly about the way women dress, both women and men will be much more relaxed when it comes to covering up and wearing modestly. The reasons would be that the social fabric there is still connected, extended families living together, and people are well connected to one another and they all consider themselves as one big family’.

Consequently, the reason why sometimes there are less restrictions on ‘covering up’ is not a lack of belief in modesty; but, it is more of an appreciation to the surrounding society members and considering them as family.

A flawed law

The Public Order Law, which was created in 1991 by the former National Congress Party (NCP), had and still has an incomparable influence on the women’s dress code and the mindset of many Sudanese women and men. This law was established as part of the former government’s attempt to transform the Sudanese society to an Islamic society, greatly emphasising on women’s clothing. Although after the 2019 revolution, the Sovereign Council removed the law in November 2019, yet it is important to see how its politics and dynamics seem to still linger on the society to this date.

‘Although the law was repealed, the mentality of the Sudanese man is not changing anytime soon. These ideologies need decades to vanish and it all starts with raising awareness and open discussions,’ said Hadeel Osman, a stylist and founder of Davu Studio.

Under Sudan’s previous public order system, Sudanese women used to face arrest and punishment of up to 40 lashes if they violated Article 152 of the Criminal Act of 1991, which broadly prohibits ‘indecent and immoral acts’. The word ‘indecent’ was very vague, which led to many incidents of the Public Order Police arresting women and flogging them for different interpretations of “indecency”.

The reason why this law continued for almost three decades, despite local and international efforts and petitions by activists to end it, is that the community enabled and encouraged it. As previously mentioned, the Arab patriarchal culture is a cornerstone to the Sudanese culture, which automatically gives men the upper hand and undermines women’s roles and voices.

For example, females feel obliged to wear the scarf although they do not wear the hijab, because they need to feel a sense of safety and protection from public scrutiny.

Commenting on the aftermath of the Public Order Law, Sara Suleiman, a social and political activist with a master’s degree in Gender Studies from SOAS University of London, said:

‘The Public Order Law’s mindset is still ingrained in today’s society. The idea of judging a woman by her looks and specifying what makes a good woman and what makes an indecent one is still a problem that Sudanese women face. This law had allowed men to take greater control in the public sphere: the markets, transportations, streets and neighbourhoods. Men still judge and believe they are entitled to dictate what a woman should wear in public or not. They also believe they are entitled to approach or abuse women, if the women are not abiding by the “decent clothing’ rules”‘.

‘The Public Order Law was made based mainly on patriarchal ideologies which politicised religious beliefs and applied them in an uncivil manner. Men now genuinely think that they have a higher ranking on women because of the misunderstanding of the religious term of guardianship ‘Wilaya”‘, she added.

There is significant emphasis on modesty in Sudan for various reasons. Yet, there is a question to ask: Has the Sudanese community limited modesty mainly to the women’s clothing and dress? Do we see any cultural practices that contradict such heavy importance in modesty in the country?

Stay tuned for Part II of ‘Modesty in Sudan’ series where I attempt to look into some cultural practices in Sudan.

Sara Gabralla is a freelance journalist who is based in the USA and a former Public Relations Consultant. She studied journalism in the American University in Dubai and also a holder of The Middle Eastern Studies Certificate. Sara aims to shed light on stories about fashion, and cultural, religious and political issues within the Sudannese community and Diaspora, as well as issues of the Islamic community around the globe.