Modesty in Sudan | Part III: Facing Patriarchal Power

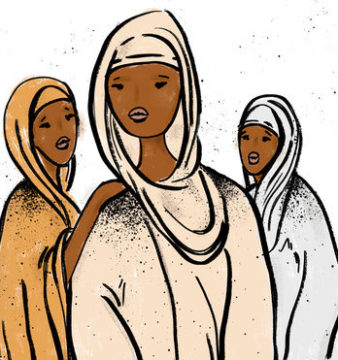

As part of the “Modesty in Sudan” series, we continue to explore and evaluate factors and reasons to why there are what seem to be ‘ambiguous and conflicting practices’ when it comes to women’s modesty and dress code, as mentioned in the previous article of the series titled: Cracking the Cultural Code.

In this last article of the “Modesty in Sudan” series, we shed light on a main factor, which appears to be fueling several beliefs and notions that shape the concepts and general understanding of modesty in many communities in Sudan. This main element is patriarchy, which shows signs that it is infused heavily in the social and religio-cultural beliefs that the majority of Sudanese people appear to abide by.

A main misconception

One of the reasons why patriarchy is sometimes allowed and overlooked in the Sudanese community is the huge misconception about the term guardianship or qawama. As defined by Palestinian Islamist writer Bassam Jarrar, qawama is to stand amply firm with a steady purpose. Men are recognised as the qawama, held responsible to look after the interest of the women in their household.

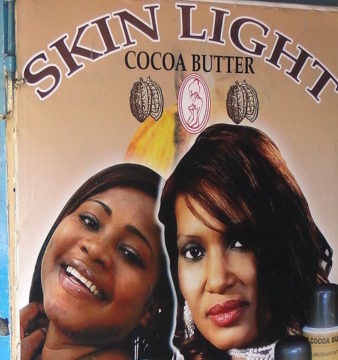

As mentioned in the first article of “Modesty in Sudan” series, Professor Marwan Al Absi, author of “The Concept of Nudity and Modesty in Arab-Islamic Culture”, said, ‘The Arab culture perceives the human body as something exclusively intimate.’ He also stresses the sensitivity of the female body as it is considered ‘a symbol of privacy, female dignity and honour in the Arab culture.’ Accordingly, there is usually a misunderstanding of how or to what extent men can control women’s lives and actions, including modesty both aesthetically and behaviourally.

Men’s guardianship in Islam is given different interpretations by Islamic scholars, both those who are considered traditionalists and those who think of themselves as modernists.

According to Shagufta Omar’s article, “Qawama in Islamic Legal Discourse: An Analysis of Traditionalist and Modernist Approaches”, the modernist scholar

Abdullah Yousuf Ali translates the term qawama as referring to men being ‘protectors and maintainers of women’ analogous to, ‘one who stands firm in another’s business, protects his interests, and looks after his affairs.’

This interpretation indicates that men have the privilege to protect and somewhat instruct but without entirely dictating the lives of their women. As a result, there needs to be a change in some families and social classes in Sudan, where the male figures in the family still try to control women’s dress codes.

However, in Sudan, it looks like there is a general societal agreement about the fact that men can exercise this qawama not only over their female family members, but also over other women within the Sudanese community.

In the first article of the series, social and political activist Sara Suleiman, who holds a master’s degree in Gender Studies from SOAS University of London, said, ‘Some men genuinely think that they have a higher ranking than women, but this is because of the misunderstanding of the religious term denoting guardianship: Wilaya’.

In addition, creative director, stylist and founder of Davu Studio, Hadeel Osman, has commented on this problematic situation for Sudanese women saying, ‘The Sudanese woman’s dress code is more a reflection of our community’s patriarchy than a reflection of her own identity or mentality even if, in some cases, she is allowed to wear whatever she wants.’

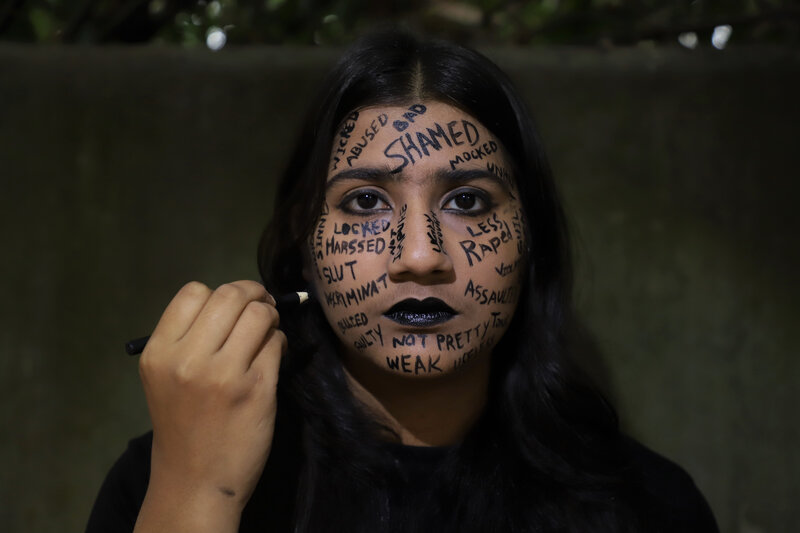

‘In other words, the Sudanese woman has to be mindful of the cultural sensitivity that prioritises the community’s standards before her mentality, beliefs or personality. There are two reasons for that. Number one is: she has to keep in mind if her outfit will offend the neighbour, the rickshaw driver or a random person in the street who might strangely take the outfit personally. The second reason is that the Sudanese woman feels the need to protect herself from the public’s verbal or physical abuse because of her clothing,’ she added.

‘A lot of the time even when we think that we are dressed up modestly or covered up, it almost feels like it is never enough,’ added Osman.

On the one hand, women in Sudan could face patriarchy on a micro-level, which sometimes arises from the immediate male family members. On the other hand, and on a macro-level, they encounter patriarchy on a day-to-day basis from males in the wider community or as a consequence of previously enforced laws like the former public order law as explained in the first article of the series.

Females fueling patriarchy?

Noticeably, it seems that some females in Sudan fuel patriarchy by their pure conviction and acceptance of some drastic patriarchal beliefs, including those about modesty and what is considered as good appearance/moral.

Hajer Othman, founder of Hosh Azza, a social platform that tackles and discusses issues, challenges and opportunities for and about Sudanese women, said, ‘Unfortunately and particularly, when it comes to the matter of modesty within the Sudanese community, most parents and community members, both men and women, view the Sudanese woman as an object or a precious good. This good/item is under trusteeship of the current guardians (parents) until it is handed to the next guardian (husband).’

‘Therefore, modesty turns from a behaviour/appearance, into a constant obsession of reputation and social judgment. It becomes important for the parents to micromanage their daughters to avoid any possible stigma. This is why a lot of the women do not dress according to personal belief but to fit social standards,’ she added.

‘I believe the reason why some older women and mothers repeatedly and convincingly practice and enforce some patriarchal perceptions is because of the social pressure that they could face if they go against the norm. In most Sudanese families, if their daughters behave or dress in any way that might even slightly be against the traditions, then they are vulnerable for being ill reputed. Thus, women keep pushing the patriarchal agenda to avoid judgment, scrutiny and gossip,’ Othman concluded.

Practical steps to diminish the ‘P’ word

The patriarchal mindset which appears to be engraved within the Sudanese community is not bound to disappear over a night. It definitely needs a consistent movement of change and a high level of awareness and consciousness to help fight it. From her experienced point of view, Dr Hadia Hassaballah, a gender professor and a human rights activist, discussed a few solutions that will hopefully help fight the patriarchy and eventually might eradicate it completely in the long run.

‘Education is key to understanding the dynamics of our community and distinguishing between facts and incorrect innovations or misconceptions that might be unacceptable socially or religiously,’ said Dr Hasaballah.

‘Being enlightened about the correct Islamic laws and regulation as well as juristic discretion are also very important elements that will boost the community’s knowledge. This will consequently help them make sound decisions about women’s rights and personal decisions,’ she added.

Dr Hasballah had referred to the Sudanese culture and how it is still important to not discard it completely as it is part of the community’s very own identity. ‘We have to preserve our traditions and heritage and enjoy our rich Sudanese culture, yet be open minded enough to let go of them if needed to avoid being misled in certain aspects of life. In our case here, women’s appearance, identity and personal choices,’ she said.

The objective of the Modesty in Sudan series is to highlight Sudanese practices and their cultural and religious implications so that we have a better understanding of the Sudanese mindset, especially when it comes to modesty, since this means that we are necessarily discussing the identity of the other half of society: women. Unfortunately, the foundation on which modesty is preached, practiced and perceived in Sudan is a blend of mixed and matched social, cultural, traditional and religious beliefs. Therefore, we need to have a better understanding of all these different beliefs and notions overall, as they play a key role in Sudanese societal encounters and daily behaviours. Here, we offer a breakdown of how the community functions and how we should ultimately offer Sudanese women the chance to take charge of their own identities and beliefs. The clash of religion and culture may lead to an identity crisis specifically for young girls and women, and they need to be able to distinguish the precepts of religion from dominant cultural practices in Sudan, if this is possible at all.

Sara Gabralla is a freelance journalist and a former public relations consultant based in the USA. She studied journalism in the American University in Dubai and also a holder of The Middle Eastern Studies Certificate. Sara aims to shed light on stories about fashion, and cultural, religious and political issues within the Sudannese community and Diaspora, as well as issues of the Islamic community around the globe.

Related posts: