Omar Al Bashir’s Ghost and the Sexual Violence Against Sudanese Women

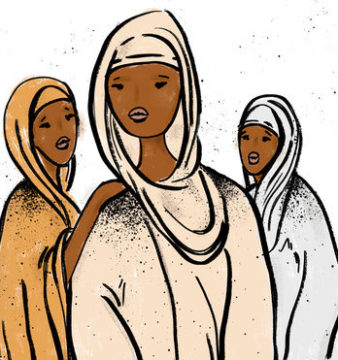

On 31 January 1995, soldiers employed by the central government of Sudan attacked an Otoro village located in South Kordofan. The onslaught happened amid the conflict between the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and the Sudanese government. The horrific incident, which involved the theft of livestock, burning of homes and mutilation of bodies, was a typical example of how the Sudanese government often took the war to civilian doorsteps. The militia employed every method to terrorise local communities, and sexual violence was a systematic tool to subjugate the opposition.

Fawzia Jibreel (a pseudonym used to protect her identity) was a 17-year-old girl who was present during the attack on the Otoro village in 1995. Jibreel described how government soldiers sexually assaulted women of her community during an interview administered by African Rights. ‘Every day the raping continued…It is impossible to count the men who raped me. It was continuous. Perhaps in a week I would have only one day of rest. Sometimes one man will take me for the whole night. Sometimes I will be raped by four or five men per day or night; they will just be changing one for another,’ she said.

The soldiers also coerced the women into selling their bodies for money and food. Eventually, Jibreel managed to escape by pretending to enter the bush to bathe.

Sudan is a nation that has seen its core shaken by civil wars, political turmoil, racism, tribalism, and religious intolerance. Omar Al Bashir was president of the country for nearly three decades before being ousted by the Sudanese military on 11 April 2019 because of the pressure from civilian protests. His administration conflicted with numerous rebel groups throughout Sudan over the country’s natural resources. These conflicts had detrimental effects on people living in Darfur, South Kordofan, eastern Sudan, and other regions of the country. The central government and its militias were complicit in creating a concealed culture of sexual violence, which included gang rape, sex trafficking, and genital mutilation. For example, Sudanese forces were responsible for raping over 200 women and young girls during an assault on the community of Tabit, a town in North Darfur, in October 2014. However, during his reign, Al Bashir continuously denied rape and other abuse accusations as a weapon of war. In a televised interview with NBC News in 2007, he claimed that rape culture did not exist within Sudanese society.

Despite Al Bashir’s denial of the gender-based violence occurring in Sudan, the widespread sexual brutality that are currently happening in the country links back to when the Islamist National Congress Party took hold of the presidency in 1989. Al Bashir’s political alliance was widely responsible for diminishing the progress of women’s rights that were achieved up until that point in time. Discriminatory laws reinforced by misogynistic views allowed the government to solidify women as second-class citizens.

Dalia El Roubi, an activist and member of the Sudanese Congress Party, recalled the influence of Al Bashir’s government and how the laws gave way to the objectification of Sudanese women. ‘I clearly remember my childhood was taken away. We were young, but we dressed freely as teenagers and pre-teens…Suddenly, everything changed: The way we dress changed, our school uniforms changed. For my generation, it was a strange experience, we had a taste of freedom and then it suddenly transformed. We became sexualised objects and our bodies became a battleground for those in power,’ she said.

Under Sudan’s Criminal Act of 1991, the definition of rape is adultery without consent. Adultery is considered a severe offense in Sudan, so rape victims must prove that they did not engage in consensual sex if they hope to receive justice in court. Consequently, Al Bashir’s administration reduced women to sexual property and granted impunity to those who terrorised their bodies.

The subjugation of women and the negation of their bodily autonomy fit conveniently into the government’s agenda of bringing destruction onto communities across the country. Although economic control over resources was Al Bashir’s primary reason for wreaking havoc on the areas outside of the Khartoum State, his administration also desired to get rid of Sudan’s non-Arab ethnic groups and tribes. Hence, government forces adopted a policy of ethnic cleansing during warfare. The idea of Arabising Sudan through armed militias encouraged campaigns of rape that targeted black ethnic groups. According to British researcher and human rights activist, Alex de Waal, there was a government policy of preventing Nuba men and women from marrying and having children by keeping them separated when stationed in peace camps. However, Arab men who served as high ranking officers and armed guards in these camps were allowed to marry Nuba women. These ‘marriages’ can be seen as coerced unions or even acts of rape when considering the power dynamics that existed within the camps.

Sexual violence as a weapon of war was a direct result of Al Bashir’s policies, his view on women, and racism towards black ethnic groups. A refugee repeated the words heard from a member of the Janjaweed (government hired militia) when interviewed by Amnesty International in 2004: ‘Omar Al Bashir told us that we should kill all the Nubas. There is no place here for the Negroes anymore.’

Sudanese women spearheaded the movements that helped push Al Bashir out of office. Although Al Bashir is no longer president, his legacy of militarised sexual violence remains. Physical and sexual assault are the consequences of the courageous and tenacious actions of female demonstrators. The citizens of Sudan are demanding a civilian government and face extreme violence from paramilitaries. There are many reports of military forces raping protestors and the medics who come to their aid. Sudanese women’s rights activists struggle to document rape cases happening during the revolution due to restrictions and fears, but rape and sexual harassment cases have multiplied since June.

The world is closely observing Sudan as the struggle for democracy continues. Legions of people have changed their social media profile pictures to blue as an act of solidarity with Sudanese protesters. The support is positive, but it is important for people outside of Sudan to learn about the complex history of the country to grasp what is happening today. Corruption, pillage, and turmoil have been common denominators since Al Bashir’s rise to power in 1989. He has looted the people of Sudan for decades, and since stepping down, has left a toxic culture that comes at the expense of women’s bodies. It is essential that people consider the issues of gender, race, and ethnic identity when analysing the situation happening in Sudan.

Muhammad Modibo Shareef is a 27-year-old Sudanese freelance writer based in Oakland, California. His work has appeared in Anastamos and The Paragon Journal. Shareef’s writing focuses on race, gender, sexuality, class, and how identity affects our politics and individual experiences. Find him on Twitter at @modiboshareef.