Sexual Harassment: A Nation’s Crisis Swept Under the Rug

A Sudanese version of ‘Three Wise Monkeys’ in Omdurman by graffiti artist Assil Diab, also known as Sudalove

Sexual harassment in Sudan is as rampant as it is repugnant. In under a year, three major sexual harassment cases made it to Sudan’s news headlines and took over social media platforms by storm — each different and worse than the last — leaving behind victims and many lives in ruins.

With Sudan turning a blind eye to this problem, it has considerably grown within the realms of normalcy. Stories, such as that of the girl, who was raped in broad daylight near the Chinese Embassy in Khartoum, and Qabbas Omar, who was sexually assaulted in a bus station, are a few which made it to the public eye. And that’s only the tip of the iceberg.

‘Last year, there were 12,300 reported cases of sexual harassment in Sudan, out of which 3,000 were in Khartoum,’ said a lawyer, who has worked on a number of sexual harassment cases, on conditions of anonymity.

While there are many definitions for sexual harassment, depending on factors such as place (e.g. workplace) and others, the legal definition is:

Sexual harassment is an unwelcome sexual advance, unwelcome request for sexual favours or other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature which makes a person feel offended, humiliated and/or intimidated, where a reasonable person would anticipate that reaction in the circumstances.

Examples of sexually harassing behaviour include:

- unwelcome touching

- staring or leering

- suggestive comments or jokes

- sexually explicit pictures or posters

- unwanted invitations to go out on dates

- requests for sex

- intrusive questions about a person’s private life or body

- unnecessary familiarity, such as deliberately brushing up against a person

- insults or taunts based on sex

- sexually explicit physical contact

- sexually explicit emails or text messages

Most importantly, the point that is often lost on people is that, sexual harassment involves a range of behaviours from mild annoyances to sexual assault and rape. However, women in Sudan are expected to tolerate behaviours such as cat-calling which can sometimes border on verbal sexual harassment.

Reinan, a victim of sexual harassment, said, ‘I won’t lie. I felt bad, cheap and slutty. It’s crazy how the first thought that crossed my mind was to shame myself instead of shaming this scum of a man who had the audacity to touch me like that. What hurt the most was that, instead of him feeling guilty, he looked me straight in the eyes and smiled like he was proud of what he had done. He behaved as if it was his right and that he was entitled to slap my behind just because he could do it.’

When asked why she didn’t do anything about it, Reinan replied, ‘I wanted to yell and slap him but my friend stopped me. She felt things might escalate as there were men all around us who will take his side and even the few girls will shame us for it.’

While women all around the world have recently taken the stand to speak out about sexual harassment as part of the Me Too and Time’s up movements, things are different in Sudan. The public outcry to hold those accountable for sexual abuse, although not very popular nor widely accepted, is on a slow and gradual rise.

When Noura Hussein’s story broke out in May 2018 — a developing story of a young Sudanese woman who was sentenced to death for killing her rapist husband — many people started anonymously posting their stories of sexual harassment on Twitter and Facebook. However, instead of receiving support for their bravery for speaking out, some of these women (and men) were attacked, only to perpetuate the cycle of victim blaming. Comments such as ‘it’s the girls’ fault’, ‘her clothes must have been too tight and provoking’, ‘the way she carried herself must have made it obvious she’s asking for it,’ and more, filled the timelines.

- Sudan is ranked 165 out of 188 countries on the UN’s Gender Inequality Index

- It has a history of rejecting the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) saying it is against Sudanese values and has only ratified the convention on 3 September 2014

- It has weak policies in place to protect and defend victims of sexual harassment leaving them in a Catch-22 situation

Anti-sexual harassment graffiti in Egypt

In a recent survey conducted by 500 Words Magazine, it was found that 273 out of 306 people (89%) had been sexually harassed. And while there was a predominance of female victims (229), 44 of the victims were men. The survey revealed that out of the 273 people who had been sexually harassed only two reported the incident to the police while the rest chose to remain silent. So why does sexual harassment go severely unreported by victims?

‘Most families fear the stigma and therefore choose not to make an official complaint,’ said the lawyer. He also added that most reported cases don’t win in court as solid proof is seldom found.

Afnan Khalid, a lawyer who has been working in a legal aid centre for women and children for the past three years, said, ‘One of the reasons many people don’t go forward with the legal process is the shortage of female investigators. It is already difficult for the victim to describe what happened to them in detail and talking to a man can be uncomfortable for a female victim.’

‘It is also very difficult to prove rape in some cases and where there is insufficient evidence, female victims are instead charged with adultery and false accusations. This scares more women away from reporting the incident.

‘There is also the financial aspect. Some people cannot afford the expenses for legal work. The process itself is time-consuming and lengthy and might require witnesses who may not show up in court,’ she added.

Moreover, 141 out of the 273 who had been sexually harassed said they were harassed by family members and family friends, which made it difficult for them to come forward. ‘The harassment was mainly from close relatives. I was scared to create family problems,’ said one of the subjects of the survey.

While one cannot identify the exact reason why sexual harassment has become so widely rampant, the women who have reported to being sexually harassed in our survey feel that gender inequality is a factor. When asked about the leading causes why sexual harassment has become widespread, lawyer Afnan Khalid said, ‘I cannot pinpoint specific causes as it is very widespread among people of all social statuses and from all walks of life. Sexual harassment is seen among relatives, neighbours, rich, poor, married, single and even Imaams of the mosque. However, the lack of sexual education in schools and from parents play a very large role.’

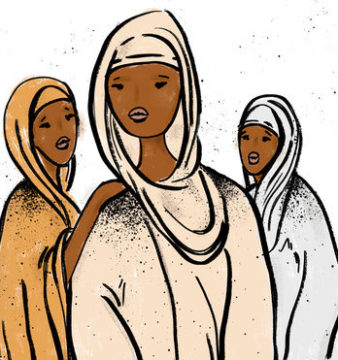

Anti-sexual harassment graffiti in Egypt. Photo credit: Wessam Deweny

‘It’s scary. Even though we are the victims, we are still blamed as we are female. Not only do we have to live with the fact that we have been harassed, but we also have to justify ourselves. We always have to stay alert and watch our backs. We live in constant fear of being harassed. While using public transportation we pray that the passenger sitting next to us is also a female. No one wants to hear about sexual harassment. Some men think it happens only to non-hijabi women and they think non-hijabi women deserve to be sexually harassed. They would even argue that if a hijabi woman got harassed, she must have done something to provoke the perpetrator. It is mind baffling and aggravating to see the victims being blamed,’ said one of the victims.

Another subject of our survey feels that sexual harassment is preventing the development of Sudanese women. ‘Sexual harassment in Sudan is an issue that plagues our society and prevents its progression. It inhibits Sudanese women from actively and confidently participating in social, professional and academic activities due to the atmosphere of fear it creates. The elimination of this social cancer, would bring unity to our nation, particularly during this difficult time with regards to our government. We do not require sympathy from men, but their solidarity. In a united fashion, this country may see an efficient work force, and a healthy and outspoken society. The termination of men’s predatory habits may finally allow women the comfort to employ their skills, amplify their voices and share their talents, for the benefit of this country,’ she said.

Another surveyee feels that it makes being a woman a liability and makes life feel unsafe.

One of the surveyees feels that it is society’s approach in ignoring such incidents that leads to increasing issues. ‘Cat-calling and verbal abuse has become a widespread issue due to our silence. We’ve been told to ignore the men who misbehave at the souq or in public transport just to avoid a scene. This applies to both women and men. If more men stood up to this, the rest would fall back and less incidents would occur. Where sexual abuse is caused by close family members, I was surprised to hear that there are many instances where young children were exposed to everything from inappropriate touching to rape. The unfortunate reality is that some people have horrifying tendencies and parents need to really keep an eye on their children no matter how young or what gender they are. Another thing to address is the lack of sex education among the youth. Opening this topic up for discussion would prevent it from being a taboo. Young boys and girls need to know what a rape kit is and its importance in proving their case. If we start campaigns on social media to educate the majority of the population about these issues, I certainly see a better future ahead,’ she said.

There is no proper way to conclude this article as so much is left unsaid and the window for this difficult conversation should remain open until a solution is found; until justice is served to the victims of sexual harassment and abuse. The Sudanese society needs to start asking itself questions. Where is the root of this fast growing weed? What can be done? Where are we going wrong? Are we raising our children right? Is it a lack of sexual education or is it the economic state of the country and the financial inability for many to get married?

So, don’t let the conversation stop here. If you have been sexually harassed speak out and if you haven’t then also speak up for those who can’t as a voice can inspire a movement and a movement can bring out change.

Afnan Hassab describes herself as your typical dreamy millennial. A 22-year-old surgeon-in-the-making by morning and a struggling writer and blogger, by night. Dedicated humanitarian, unwavering feminist, relentless debater, obsessive cleaner and a coffee addict among other things. Born and raised in Jeddah, KSA. Went to college in Sudan. Based somewhere between these two countries and more.

Afnan Hassab describes herself as your typical dreamy millennial. A 22-year-old surgeon-in-the-making by morning and a struggling writer and blogger, by night. Dedicated humanitarian, unwavering feminist, relentless debater, obsessive cleaner and a coffee addict among other things. Born and raised in Jeddah, KSA. Went to college in Sudan. Based somewhere between these two countries and more.