Sudan’s Rape Supportive Culture

In Sudan, the documented and undocumented cases of sexual violence, abuse and assault are many. Although in recent years, many rape cases came to light, it wasn’t until the revolution and mass sit-in in Al Qeyada where women, young and old, as well as men were reporting being sexually assaulted, that the society began to pay attention to the alarming rape culture in Sudan.

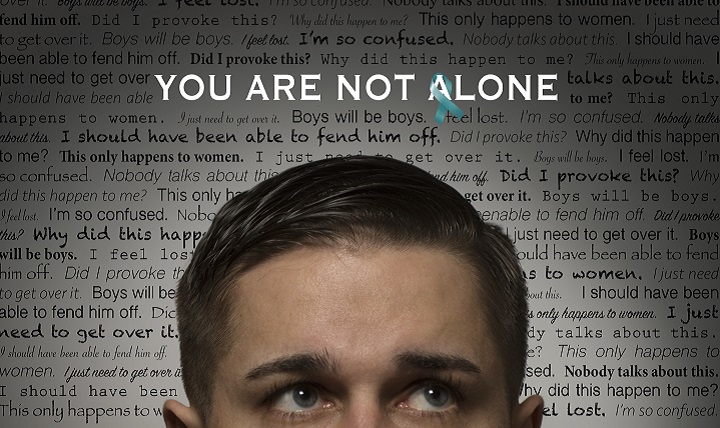

Recently, I have read and watched many rape stories that have recently began to afloat heavily on social media. The #MeToo movement has found its way into Sudan. One of the most striking videos I’ve come across was on Facebook of a man who openly shared his experience of rape during the Sudan massacre on 3 June 2019, as well as having witnessed the rape of 14-year-old girl. It was rare to see a man, let alone a woman, openly discuss rape in a society – a patriarchy society – where both males and females are unable to use their voices and share their stories of rape and sexual abuse out of fear of being shamed and blamed. Recently, a hashtag on Twitter called افضح_متحرش#, which translates to ‘expose a harasser’, began to trend, encouraging women and men to share their of sexual abuse, and to publicly expose and call out their sexual harassers.

Most of the sexual abuse and harassment victims confirmed that their abuser or rapist was a family member. Sexual consent is uncommon in our culture – even in marriage. One of the most well-known cases of marital rape is that of Noura Hussein, who in May 2018 was sentenced to death for fatally stabbing her husband – whom she was forced to marry – as self-defense as he attempted to rape her. Due to the international outcry from feminists and human rights activists, her sentence was repealed. Noura’s case helped spread awareness about sexual abuse and rape in and outside of marriage in Sudan.

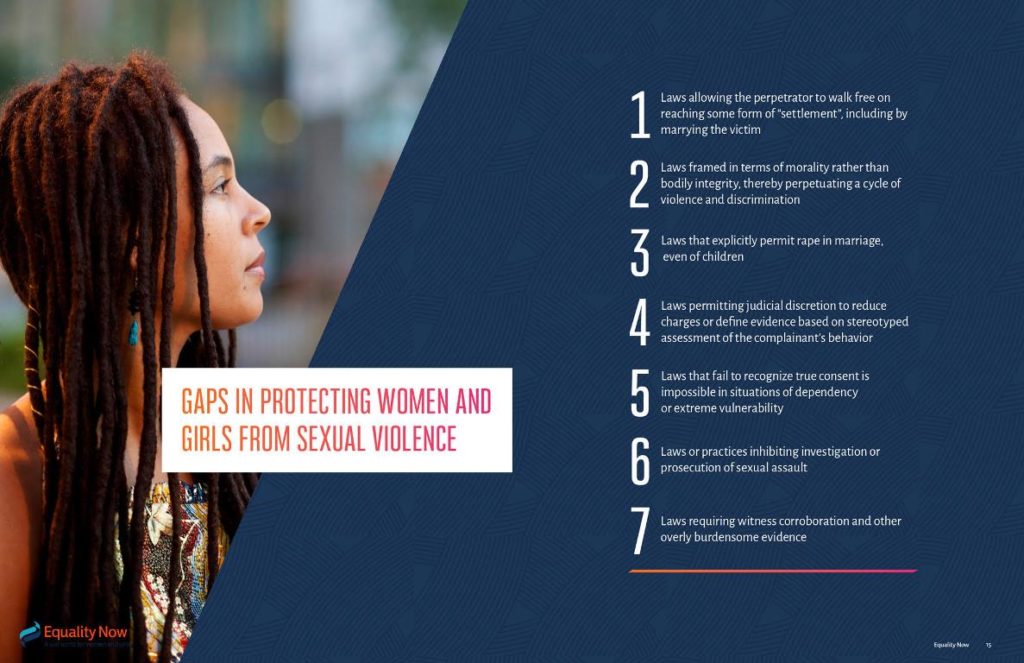

Rape crime laws, which punish rapists around the world, are directly affecting people’s behaviour towards rape and sexual harassment due to the role the law plays in criminalising the rapist and providing justice for the victim. However, that is not the case in Sudan. Due to the flawed legal system and laws in Sudan, rapists are most likely to get away with rape or get minimum punishment for their crimes. Last year, a three-year-old boy was raped by a religious cleric, who was then sentenced to only three months of imprisonment.

Rape and sexual assault are criminalised differently in countries around the world, improving their communities and successfully reducing sexual abuse-based crimes. Many countries have successfully defined and criminalised sexual assault into separate category crimes and punishments. For example, Ireland has two rape offences: one for nonconsensual vaginal penetration by a penis and the second for anal or oral penetration as well as vaginal penetration by an inanimate object. In the US, the legal definition of rape varies by state, though there is also federal definition for the purpose of crime statistics, which defines rape as the penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim. Through laws on sexual assault, countries such as Ireland, the US and New Zealand, which do have separate rape laws, also acknowledge that there are a number of other sexual offences that don’t involve penetration; these offences, however, are in some ways considered less severe.

In the past, the crime of child rape or sexual abuse, and adultery were under the same legal article, where the case of a child and her/his rapist would fall under the same law of adultery instead of being distinguished as a separate crime. It later became separated where rape crimes and adultery fall under two separate legal articles. The process of reform of the article on rape has been influenced by the country’s political situation at the time, especially by the conflict in Darfur where mass rapes were commonly conducted as a weapon of war. The controversy over the issues of rape in Darfur drew attention to the existence of sexual violence and rape crimes in Sudan especially during war and armed conflicts.

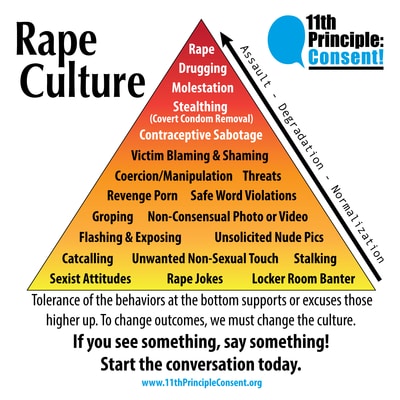

Victims of rape are most likely not to report the crime, as such types of crimes are stigmatised and unfortunately, the police and other authorities in Sudan do not have adequate training or knowledge to deal with such cases. There are many cases where rapists escaped imprisonment because of stigma – victims afraid of seeking justice due to social and cultural stigma. Women’s rights activists in Sudan must call for change in the country’s rape and sexual assault/harassment laws. But how can we change the culture is the real challenge nowadays.

Raising awareness about sexual violence is crucial and must begin in schools either as part of the sex education in the curriculum, or by introducing new tools of teaching about gender-based violence and human rights from an early age. In addition, men must be involved in such awareness campaigns where they are educating and influencing each other. However, the debate is really complex, as many feminists believe that the stand for women’s rights should be conducted without the involvement of men. There is an gap between men and women, where most don’t understand what a feminist stands for and what rights do they want for women. On the other hand, there are many women who either don’t know or understand what their rights are, or prefer to give in to the patriarchy system.

At this stage, this gap must be closed by educating those who surround us, including men who can influence their male peers, especially radical masculine men. There is progressive male group in Vienna who believes that there must be male movement to break the patriarchy system, and end gender-based violence. However, this group gathers on a monthly basis in order to discuss how they can get rid of their toxic masculine concepts; to reflect on how they used to think of women (sisters, mother, and their feminist friends); and how they can evolve in order to unlearn the toxic lessons instilled in them by their upbringing or society when they were younger. How we grow up learning about our rights as individuals plays a role in the outcomes, behaviours, and understanding of boundaries in society.

Glossary

Sexual offences: A sexual offence occurs when your physical body is interfered with in an inappropriate way by another person, that is when a person deliberately touches any part of your body including your private parts in a sexual manner or way and/or by sexual intercourse, all without permission or consent. A sexual offence may also occur through telephone calls, texts, emails, letters, pictures, videos or messages of any kind in order to engage in behaviour that is sexual in nature.

Sexual harassment: Unwelcome or unwanted sexual advances, requests for sexual favours, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature.

Sexual abuse: Unwanted sexual activity with perpetrators using force, making threats or taking advantage of victims not able to give consent.

Child sexual abuse: A form of child abuse that includes sexual activity with a minor. A child cannot consent to any form of sexual activity, period. When a perpetrator engages with a child this way, they are committing a crime that can have lasting effects on the victim for years. Child sexual abuse does not need to include physical contact between a perpetrator and a child.

Sexual assault: Refers to sexual contact or behaviour that occurs without explicit consent of the victim, including attempted rape; fondling or unwanted sexual touching; forcing a victim to perform sexual acts, such as oral sex or penetrating the perpetrator’s body; and penetration of the victim’s body, also known as rape.

Rape: A form of sexual assault often used as a legal definition to specifically include sexual penetration without consent. Rape is defined as penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.

Wala Ahmed Elfadul holds a bachelor’s degree in management information system (MIS) from Ahfad University for Women (AUW). She is a highly active volunteer in women right’s cases in Sudan. During her university, she worked closely with Ahfad Trauma Center to tackle women’s rights issues in Sudan. Recently, she joined the reproductive health and sexual rights network in Sudan. Wala, along with group of other women rights activists, have conducted awareness campaigns during the sit-in at Al Qeyada during the revolution, to tackle the phenomena of sexual harassment. Wala has been selected to be one of young female leaders in Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI) RLC East Africa in Kenya. Wala has also become part of IFA network in Germany, where she has worked on Digital Foundation that focuses on building educational platforms for young children in different age range.

Sexual abuse is one of the historical forms of oppression that all ancient nations had experienced. It was not only used for pleasure, euphoria or insanity; but mainly for revenge, punishment or humiliation.

Despite the efforts of activists and campaigners; victims are mostly lonely, silent, traumatized and stigmatized. However; there are three phenomenal categories that can be identified in this matter:

The reflection of advanced simulations of adequate living, interpreting whatsoever schools of thoughts and technologies had delivered, or opened the minds for more. This is the civic rationales of the developed countries. Yet; continue to debate the definition of consensual response.

Secondly; the violent evolution of new social culture among developing communities, which has direct and indirect accesses to various materials to initiate social reforms and freedom of expression; yet land on thresholds of unlawful sexual misconduct or stresses; which receive notable penalties.

Thirdly; the deteriorated living of underdeveloped communities that are mostly controlled by religious and folkloric norms; whereas sexual abuse survives in various hidden or unspoken forms. This includes family, kinship or community abuses as well as by forcible, criminal or lordship abuses. Such politically-corrupt communities have inconsistent and immature legal systems to address the matter.

Most of Arab, African and Muslim countries fall within the third category. Sudan is no exception. Yet; it is hard to find the way forward to restore humanity and dignity that were abused for very long; and turned to be the norm.

Within this category; abusing wife by her husband, daughter by her father, female relative or kinship by her uncle; are usually unreported. Abusing boys, adolescents and adult men is usually carried out by authoritarian or criminal males. Both forms epistemically represent the predominated patriarchal structures.

Due to spreading of poverty, illiteracy and ill-preaching, it was proven failure to relay on religious or moral parameters to draw the righteous conduct. Even so, harsh punishment is not strong deterrent for the abusers. Yet, the universal surveys would suggest no successful tools are available to compact the abusers, except empowering the females to shamelessly and confidently object, fight and report abuses; while a serious authority would punish the abusers.