Beyond Recipes: Omer Eltigani brings Sudanese cuisine to the world

Omer Eltigani’s new project is an ambitious one. He’s writing a Sudanese cookbook. Leena Habiballa finds out more in this exclusive interview.

You never truly appreciate your mama’s or haboba’s cooking until you brave the kitchen to cook Khudra one day and inflict your pot with 8th degree burns in the process. Those of us who move out of our homes before learning the secrets of Sudanese cooking from the women in our lives, experience a strong culinary nostalgia in our distance. Images of onion sautéing into a glistening, golden brown or powdered meat melting in a sea of fresh salsa linger in our minds. You long for the fresh, yeasty aroma of guraasa, the sight of sprinkled herbs swirling in a mufraka-induced tornado of leathery, brown mulah, and the strong smell of chlorophyll and earthy vegetables lacing the air on Friday afternoons.

While away at university, a similar yearning for his mum’s cooking sparked Omer Eltigani’s interest in the cuisine. “At first I was spending time with my mother and writing down my favourite recipes. Then I began to talk to other women in my family about the culture around the food. I found this fascinating and began getting into these discussions more and more.” Omer’s curiosity soon transformed into a 3 to 4 year long project to bring these meals to kitchens all over the world.

“On visits to Sudan from the UK, I’d make trips to specific restaurants and arrange meetings with history teachers, neighbours, distant relatives, house employees and friends of friends to get the information I was after,” says the 32 year old, who gave up his job as a hospital pharmacist to travel across the Americas and pursue writing his book.

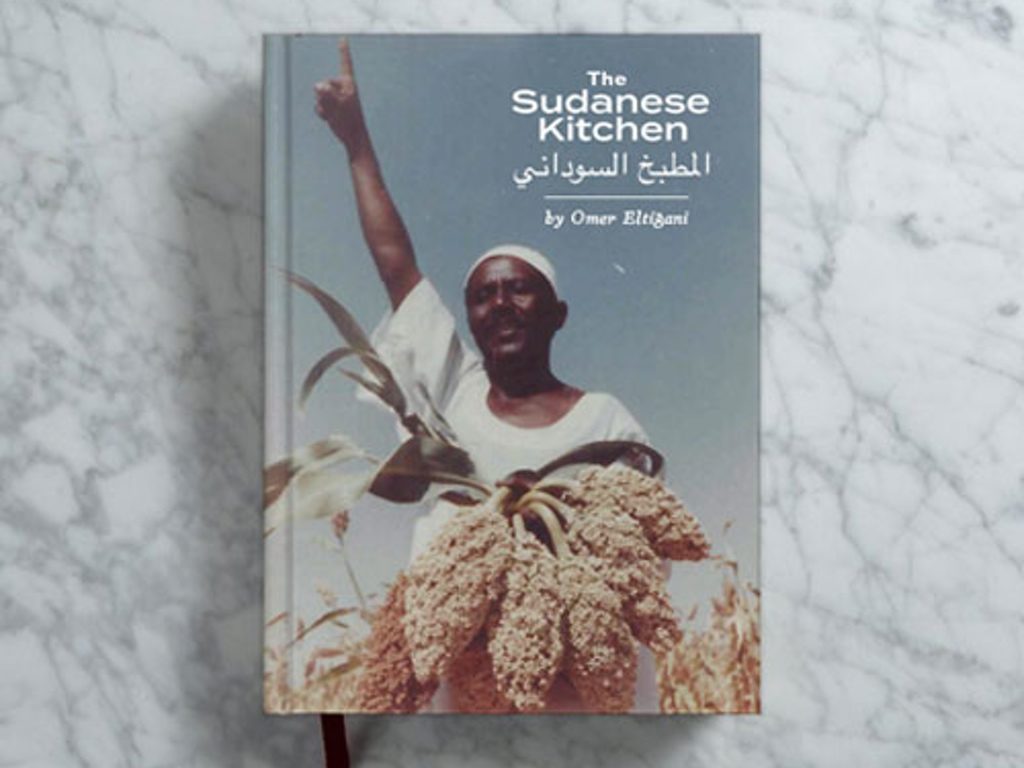

The space of knowledge about Sudanese recipes and ingredients has for a long time been a woman’s domain restricted to the privacy of the home and passed down generations orally. The Sudanese Kitchen, Omer’s cookbook-in-the-making, aims not only to provide a physical record of this intimate information but to explore the historical and socio-economic aspects of Sudanese kitchen politics. “The more I worked on it, the more the project became about the link between cuisine and culture and the way they are shaped by the social and political climate.”

I recently interviewed Omer to find out more about The Sudanese Kitchen and his thoughts on cooking in diaspora.

Omer Eltigani at the opening of the Sudanese Kitchen pop up in East London. He aims to give people a taste of Sudanese culture by preparing and sharing authentic Sudanese recipes.

Leena Habiballa: I have been so excited about your cookbook and its scope since I heard about it. Tell us what you’re hoping to achieve by writing The Sudanese Kitchen?

Omer Eltigani: It’s important for me to put this book out, for myself and for the Sudanese people. The Sudanese identity has either been fragmented or shrouded in lies. My book attempts to clear the fog of deceit and ignorance. Identity and heritage are expressed in many ways and none are more noticeable than the food you eat. By displaying historically accurate information about this food heritage, I hope that we, as individuals and collectively, can learn important lessons about our nation and identities and learn to accept and celebrate them with pride. We are what we eat and I believe that looking into our food will uncover crucial parts of ourselves.

Leena: You say on the Kickstarter page that Sudan has often been misjudged by the rest of the world. In what way(s) do you feel people have misunderstood Sudan and Sudanese people? In what way(s) has this personally affected you, if at all?

Omer: When people in the outside world think of Sudan, they think of war, famine, radical Islam and not a place they’d like to be. They don’t see what we, as Sudanis, see when we are there, which is a rich culture and warm embrace. Of course it’s clear to me that these conceptions have a basis in reality and obviously, genocide deserves more attention than my morning ligaimat. I guess I wanted to make a project that celebrates the country while negotiating its current issues and give an informed view of the country with all its gems and flaws on show.

Leena: What has/have been the biggest challenge(s) in pursuing this project and what keeps you going in the face of it/them?

Omer: It is definitely a challenge to be writing objectively about a country as diverse and complex as Sudan. I want to represent all the communities within the country, include factual information and establish an understanding of a cuisine that can take many shapes and forms. My own added challenge is that on top of defining the indefinable cuisine, I am also providing a historico-geo-socio-political context to introduce the country to those unaware of its turbulent history, varied cultures and current social and political climates and communicate their effects on the cuisine and culture.

What keeps me going is my determination and passion to finish a project I started and hoping its outcome benefits many others inside and outside our community.

Leena: What was your relationship to cooking prior to embarking on this project?

Omer: Slim to none. I couldn’t cook very well at all and in fact a short time before I started writing, my brother and I lived together in Manchester for a year and he would often cook us great dinners. Through this project I’ve learned the basics and cultivated my own cooking style. Now I’m happy to cook for many people – it’s always a matter of practice.

Leena: What were non-Sudanese people’s reactions when they tasted your Sudanese cooking?

Omer: They love it of course, and I’m not even making it right! They like the use of peanut (unless they’re allergic to it). They say it’s a good mix of meat-and-veg with a sauce that seems healthy. They love the use of spices and the balanced flavours and textures as well as eating with their hands. It’s a fun new experience for them.

Leena: How do you feel your research has enhanced your appreciation of Sudanese food and helped you reconnect with Sudanese culture, if it has at all?

Omer: I definitely appreciate the work that goes into making Sudanese food and its broad diversity more. Across Sudan, no two recipes for the same dish are ever the same and these differences are coloured by so much complex history. My research has highlighted the link between food and culture much more clearly for me and because of that I now have a greater appreciation of Sudanese culture.

Leena: How have you tried to maintain the diversity of the recipes so as to represent cuisine from as many different parts of the country as possible?

Omer: In each section of the food chapters I’m going to try to provide a variety of recipes from the different regions of Sudan. I also want to include some recipes from South Sudan even though it is a different type of cuisine. It is more of a political statement that I’m making that I see Sudan as one, unified in races, cultures, traditions, religions and ways of life, an acceptance to transcend all boundaries between humanity as obsolete.

Leena: I’m curious to know why you didn’t take the more academic route with respect to the research behind this project in order to secure funding and tap into resources necessary to synthesise the chapters in the book?

Omer: I didn’t want this to be an academic project. I wanted to make a cookbook that’s accessible to everyone and that could be part of everyday life that also introduces the country it’s talking about which so many know so little about. There is definitely scope to go into academia following this project with potentially a follow up book that goes deeper into Sudan’s culinary anthropology.

Leena: I imagine that some of the information in the book even Sudanese people might not know. What do you think they’ll find most surprising/interesting from your research so far?

Omer: Nice try, they’ll have to find out. Remember in The Matrix when Neo takes the red pill? It’s gonna be like that!

Leena: It’s very odd to me that Sudanese food is not more popular abroad where there is a sizeable Sudanese population. Sudan is a really culturally and historically unique place and we have a lot of interesting facets to our culture, especially our food. Why do you think more Sudanis don’t share their food with the world?

Omer: I really don’t know, you’ll have to ask them. I do know that Sudanese food is becoming somewhat of a trend over in Germany, which has received many asylum applications as conflicts continue to rage in Sudan. These groups make food to get by like many other migrant communities around the world. The rest like my own family left Sudan in the educated brain-drain movement back in early 90’s and had other jobs to fall back on. For these communities Sudanese food was something to be had at home and with the family, not shared with the outside world for lack of necessity.

I’m glad the tides are changing now and more people are becoming aware of how great our food is. I’d like to not only provide the information on how to make the food but also an understanding of the Sudanese experience in general by spreading information that can liberate us from its restrictions.

Leena: Would you ever want to open a Sudanese restaurant someday?

Omer: I think the enterprise of running a restaurant in general is not one I gravitate towards. It seems very stressful and like you’re constantly busy/working. This is the opposite of what I’d like out of life so probably not. Having said that, my dream isn’t far off: instead of a Sudanese restaurant, I’d settle for a small café that serves breakfast at 8 and lunch at 1, somewhere by the sea and where I can grow some vegetables. That’s more my pace.

Leena: I find that restaurants that specialise in a geographically-specific cuisine are usually places for those in diaspora to reconnect with their culture and to build a sense of community. In the general absence of that for the Sudanese diaspora, what was your alternative growing up?

Omer: My parents had lots of friends in the Midlands and my cousins were nearby so they’d take us to their houses quite often. I guess we connected and reconnected with our culture quite a lot at those gatherings. As I got older and there was a more marked absence of the Sudanese diaspora, I befriended those whom I could relate to, brown and black folks, those who shared my experiences and saw the world as I did and were similarly navigating a familiar yet foreign land.

Leena: And finally, are you Team Kisra or Team Guraasa?

Omer: Team guraasa I’m happy to say. The texture is great and goes well with the mulah(s) it is served with and is really filling. It’s also more versatile than kisra since it can make a great dessert.

No official release date for the The Sudanese Kitchen has been announced. You can keep up with the project’s exciting developments and updates on Facebook and Instagram.

Leena Habiballa is a global soul of Sudanese origin and co-editor at Qahwa Project. UCL graduate and geneticist by training, social worker by heart, poetrartist by dreams. Her work has been published on Media Diversified and Al Tayr Al Muhaajir. Her talents include 7.9 Richter-scale-measuring sneezes, half-reading 10 books simultaneously and playing the drums. Follow her on Tumblr: All Sudan Everything.

Leena Habiballa is a global soul of Sudanese origin and co-editor at Qahwa Project. UCL graduate and geneticist by training, social worker by heart, poetrartist by dreams. Her work has been published on Media Diversified and Al Tayr Al Muhaajir. Her talents include 7.9 Richter-scale-measuring sneezes, half-reading 10 books simultaneously and playing the drums. Follow her on Tumblr: All Sudan Everything.