Beyond the Coup: What Does Falling Back to the Dark Ages Mean for Sudan’s Economy

In Elazhary, South of Khartoum, construction is underway for Mohamed Elbagir’s, a 32-year- old university graduate, modest veranda in his shared family house. The narrow shed, covered with iron sheets, is his office space for his recent gig. He exchanges mobile money for cash in return for a commission for the registrants of Thamarat, a cash transfers programme and an attempt to cushion ongoing economic reforms in Sudan to which low, middle and some upper income families of the block have hurried to register.

Elbagir’s veranda is yet to be complete, but Thamarat’s fate seems unknown as many donors have put their Sudan operations on hold after the coup d’etat, which took place on 25 October 2021, led by the Commander in Chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), General Abdel Fattah Al Burhan, announcing taking over the government, calling it a move to “correcting the transitional passage”.

Sudan’s economy has recently begun to experience slight improvements in its macroeconomic indicators – an aligned exchange rate, and a somewhat plummeted inflation – attributed to austerity measures and reforms that led to lifting fuel and wheat subsidies, public foreign currency auctions, being delisted from US’s SST list and gradually opening up to international banking; notwithstanding, the shadows of the COVID-19 crisis and the prevalent bread queues and occasional fuel lines.

During a weekly coffee ceremony, the ladies in my block, and between a supporter and an opponent, have strongly debated the legitimacy of the coup, but they seem to have agreed on one thing – a mutual concern for losing their Thamarat stipend and a complaint about not having Sila’ty initiated in the block yet. Sila’ty is a national programme for providing reduced prices for 18 consumer goods through co-ops.

In addition to the blood, sweat and tears of the young Sudanese people, this recent militant manoeuvre not only halts any efforts to move forward, but it also tosses Sudan’s economy back to the dark ages. In the short-run, this could mean a few things.

Increased expenditure on security, leading to decreased share of other essential budget lines such as health and education

It has been reported that during late years of the former regime, Sudan’s security expenditure exceeded 70% of its total budget, and with investments from literally a needle to rocket, the military/security investment apparatus expands from flour, slaughterhouses, mining, to army machinery production. These companies owned by Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), Rapid Support Forces and General Intelligence Services, and GIS. There is no accurate valuation on this secretive system, but for instance, a 2020 report suggested that Al-Junied, an RSF established company makes around USD390 m a year, and the Kadaru Slaughterhouse is worth USD40 m. These companies have managed to escape public audit with the claim that they are security-based entities. A persisting popular demand has been retaining those companies under the umbrella of the Ministry of Finance.

Rumour has it – and living in Khartoum teaches you that many rumours are somewhat true – that just before the coup, the top Generals approached the civilian arm of the government asking for access to the Central Bank foreign currency reserves, to finance transactions related to the forementioned apparatus. Their demand was faced by strong refusal from the Bank, which might be a cause for the rapid sacking and potentially disappearance of the deputy governor of the bank right after the coup.

The Committee for Dismantling the 30 June 1989 Regime is losing its track

An article of the constitutional document as a main revolutionary demand established the Committee for Dismantling the 30 June 1989 Regime, which was led by a top General from the Sovereignty Council and a civilian member of the same council. The committee’s acts did not sit well, not only with members of the previous regime, but with affiliates to the regime’s colossal economic empire, including security and military members. Despite claims of the committee’s overestimation of the confiscated assets, lousy investigations, inadequate legal basis, and ongoing shenanigans between the Committee and the Ministry of Finance regarding sheltering these funds back under the state’s budget. Members of the Committee have never hesitated in pointing fingers towards blockers from the militant arm of the government, which has increased their popularity within the revolutionary crowds.

In a statement, Al Burhan has announced the indefinite suspension of the constitutional articles governing the Committee’s work, and the alternate head of the Committee has been forcefully detained since 25 October. This threatens the ongoing investigations, and what is more concerning is the release of the former regime’s affiliates arrested by orders from the Committee, such as National Congress Party (NCP)’s notorious financier, Abdel Basit Hamza, unleashing the reactivation of many assets that has been controlled by NCP and allowing many affiliates to catch their breath and potentially escape justice, if not already.

Continued state capture: losing control on Sudan’s gold reserves

Gold, or the saviour that appeared after oil rents departed the state, has shifted the narratives of public revenues in Sudan on both economic and political ends.

From militia capture, traces of shady international involvement outside the official State records, and favourable negligence of the Sudanese Company for Mining Resources; gold smuggling has boomed during the past three years. The lack of a firm, independent control of these reserves will not only endanger the public budget, but whatever entity that is in control of these assets, has the upper hand in making decisions regarding its lavish disbursement.

Going back to trade isolation and shattering aid funds

As many international donors suspend their aid and development operations in Sudan, the country seems to be sliding back into the ages of international isolation, where it was only eligible to limited humanitarian pools and forbidden from trading with many countries and international cooperations, and sometimes this included medications and essential spare parts.

Risking losing talented human capital and meritocracy-based employment:

The 30 years of the former Sudanese President Omar Al Bashir’s regime has not only infiltrated the political sphere, but has also systematically destroyed the civil service system, deeming it unappetising and unwelcoming to the talented, not to mention the very small financial incentive linked to been a public servant, consequently leading to brain drain. This has started to change after the inauguration of the transitional government. Many talented expatriates felt the opening civic space would allow them to return to Sudan, and many younger talents sensed the need to strengthen the public sector to foster the transition. This was accelerated with international donors pouring funds into talent acquisition programmes, and seconding senior staff to state counter parts, with encouraging salaries.

Outside Khartoum, state, and locality governments might have not received as much ivy league graduates and 21st century skilled staff, but public servants were under the pressure to improve their performance given the revolutionary spirit and an overall increase in social auditing, informally practiced by citizens that have recently regained their voice to right the system.

All this seem to be shattered, the military top general has been, and on daily basis, firing many of these newcomers, and hiring many that have clear affiliation of the previous regime or outspoken blessing of the coup, with no evidence to their meritocracy. One immediate result is that a recently announced, donor-funded young professional programme aiming to provide technical support to the Federal Ministry of Finance, has been put on an indefinite hold.

While Khartoum’s elite shy away from calling Sudan’s 2018-19 revolution a hunger revolution; about 25% of the Sudanese are estimated to be acutely food insecure, causing political economy factors into reshaping the new alignments across rural and peri urban Sudan.

For instance, the preparations for the winter season are underway across agricultural schemes and extensions; hand in hand with harvesting the products of the summer season, a period that witnesses massive outbreaks of violent incidences among herders, farmers, and armed gangs – a recurring historical conflict. To curb any frictions, a massive mobilising of the army and RSF on the so-called “the committees of securing the agricultural season” has been taking place in recent years. However, this time around, an interlocuter in East Darfur confirms that Rapid Support Forces (RSF) troops have been shifted from their seasonal duty back to the cities to contribute to controlling unwelcome demonstrations after the coup.

And by this, Sudan continues to assume its traditional position, only looking at its federal political brokering and overlooking shattering economic problems that could sweep entire communities, threaten food security, and encourage displacement and mortality for a wide spectrum of the rest of the Sudanese people.

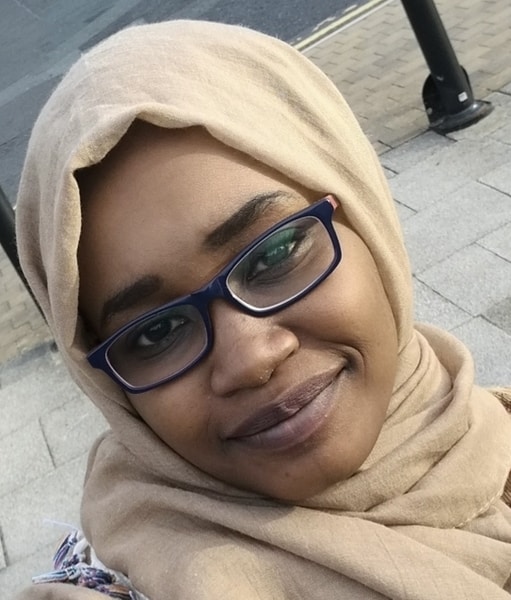

Jawhara Kanu is an economist, development practitioner, and a founding member at the Sudanese Women Economists Association (SWEA). Since completing her formal Economics training, from University of Khartoum, and later the University of Bradford, she has been working in development projects implementation in Sudan and a wider focus on the African continent.