Glyphs and Alphabets: The History of Writing in Sudan

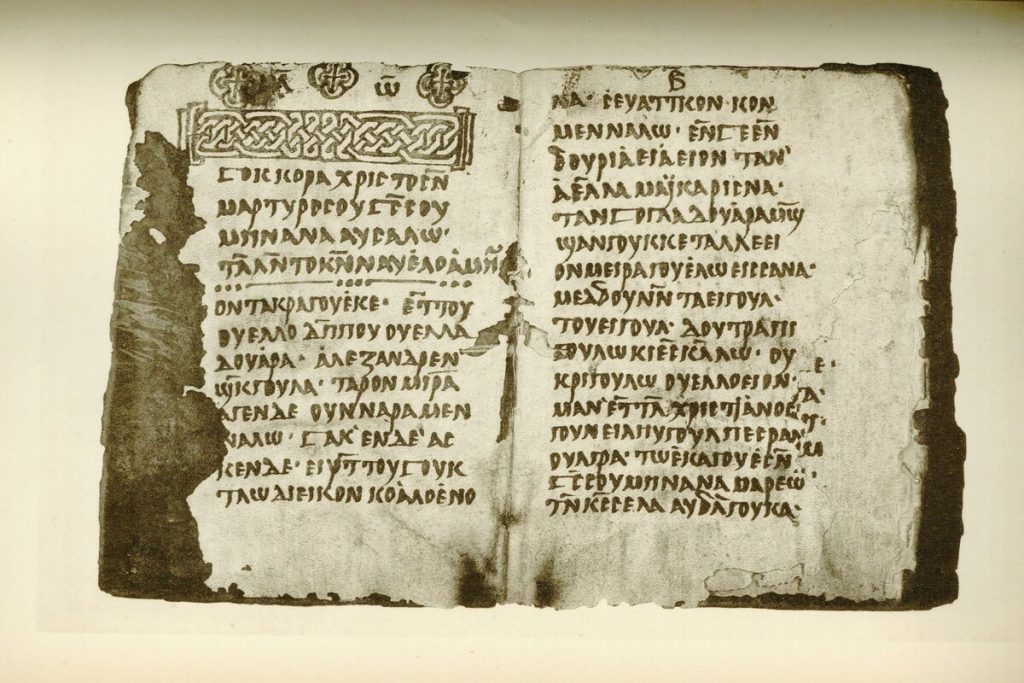

11th-century manuscript of the Miracle of Saint Mena, a story about the famous Coptic saint, translated to Old Nubian. (Source: Reddit)

With complex states like those of Sudanese history came the need to record information too inconvenient to memorise. As a result, Sudan boasts over 2,500 years of written culture, one of the oldest histories of writing in Africa. This history is the story of an internationally aware local elite who adapted writing systems circulating in the region to log sales, worship, history, and more.

To study their written legacy is to study the intertwined histories of language, religion, and politics – a lineage that culminates in modern Sudanese society, where formal, elite written culture co-exists with a decentralised world of informal writing made possible by the digital age.

Kingdom of Kush

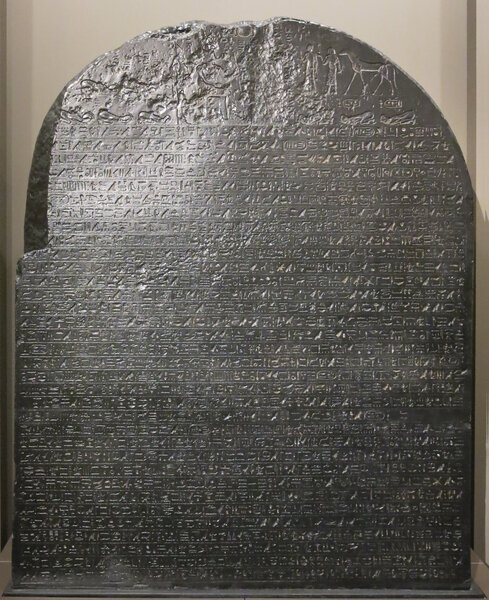

By the first millennium BCE, a region known as Kush – encapsulating historic Nubia, the area from Aswan to Khartoum – had been a part of the New Kingdom of Egypt for nearly five centuries. This period of Egyptian administration popularised the use of Ancient Egyptian as the elite language. Therefore, when Kushite rulers took over the state in 750 BCE, Egyptian hieroglyphs were used to record Kushite military achievements and religious texts.

However, just because a language is written does not mean it is spoken. While Egyptian was the prestigious written tongue, Kushites spoke other languages, as seen in their personal names. At first, they transcribed these names with hieroglyphs or Demotic, a cursive form of hieroglyphic writing. Eventually, Kushite scribes modified Demotic to write non-Egyptian names more easily, even in otherwise Egyptian texts.

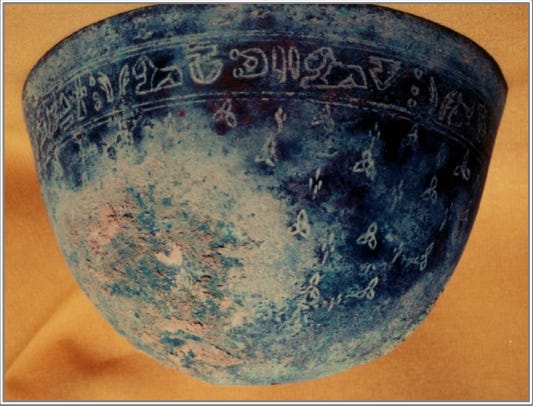

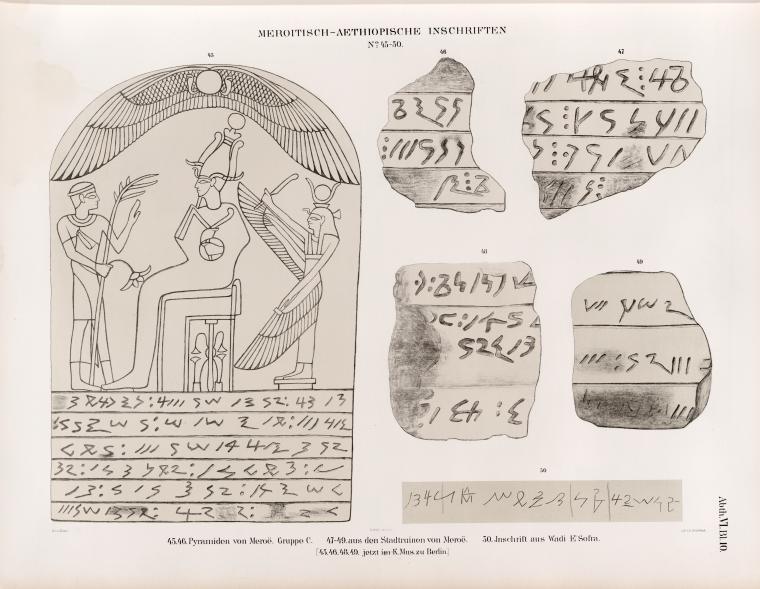

After the Kushite royal family moved its administrative capital from Napata to Meroe, scribes began using this script for full texts in a Kush-exclusive literary language. Scholars have come to call both this script and the language it was used to write ‘Meroitic.’ Eventually, it replaced Egyptian as the language of royal inscriptions.

The rise of distinctly Kushite architecture and religion in the Meroitic period shows that the shift from Egyptian to Meroitic was part of a broader cultural shift from northern Kush (closely tied with Egypt) to southern Kush, demonstrating how elite sensibilities shape writing.

While Meroitic and Egyptian were dominant, Kushites also encountered Graeco-Roman culture through Roman Egypt, influencing architecture, pottery, and writing. While the number of Greek texts is small, this interaction with Mediterranean culture will lay the seeds for the next major shift in the history of Sudanese writing.

Christian Nubia

By the 5th-century CE, the Kingdom of Kush had fallen, and was succeeded by the Christian Nubian kingdoms of Nobadia, Makuria, and Alodia. These new kingdoms, encapsulating all of modern Sudan except Darfur, were ruled by a new Christian elite converted by Byzantine missionaries. This changed ideas of prestige, and writing in the region moved from the Meroitic-Egyptian scripts – closely associated with Kushite-Egyptian religion – to the Greek script used in Byzantium.

Once limited to Roman visitors to Nubia, Greek became the primary sacred language in the Christian-era, used in everything from sermons to epitaphs. In Makuria, the Coptic language was also used, especially outside the capital city, Dongola.

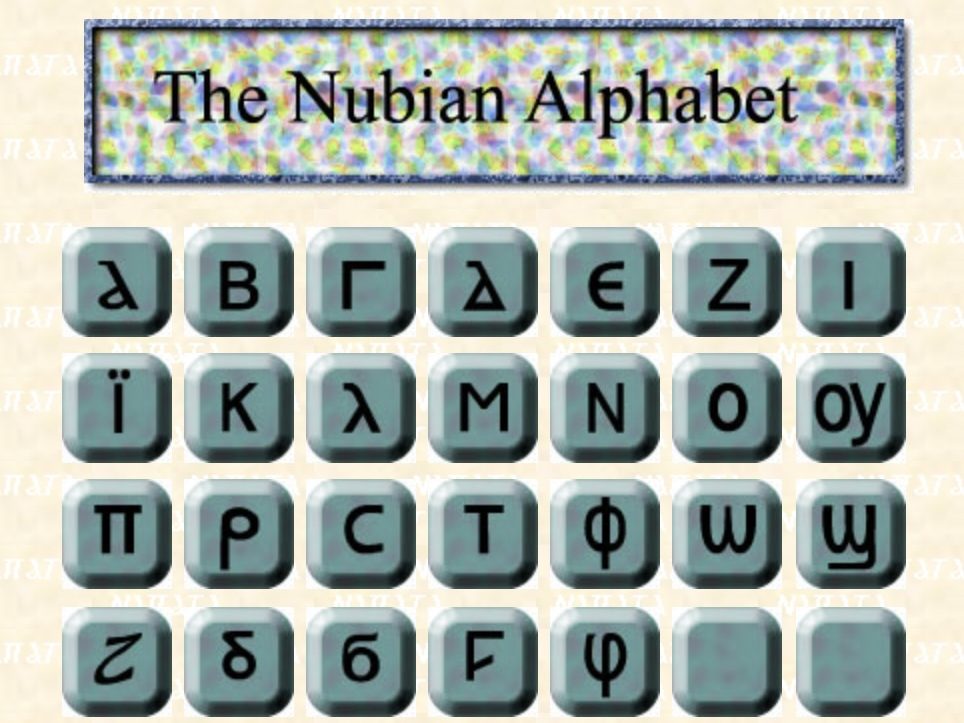

While these languages held prestige locally and regionally, Nubian elites soon felt the need for a more familiar literary language to effectively spread their religion. This resulted in the birth of two Greek-based scripts, for two new literary languages: Old Nubian, the ancestor of today’s Nobiin language, and Old Bidawiyet, the ancestor of today’s Beja language.

Old Nubian was developed during the 6th-century, based on a style of Greek writing pioneered in the Egyptian White Monastery. Known as the ‘Nubian-type majuscule,’ this slanted, all capital style was initially used by Coptic scribes to distinguish titles from the main text.

Nobadian scribes took this style and added three Meroitic letters to write Old Nubian texts visually distinct from Coptic. Soon, it became the language of the Nobadian government and economy. It was later adopted as the elite language in Makuria after its annexation of Nobadia in the 8th-century. For the next 800 years of Makurian rule, Old Nubian would be the main language of government and religion.

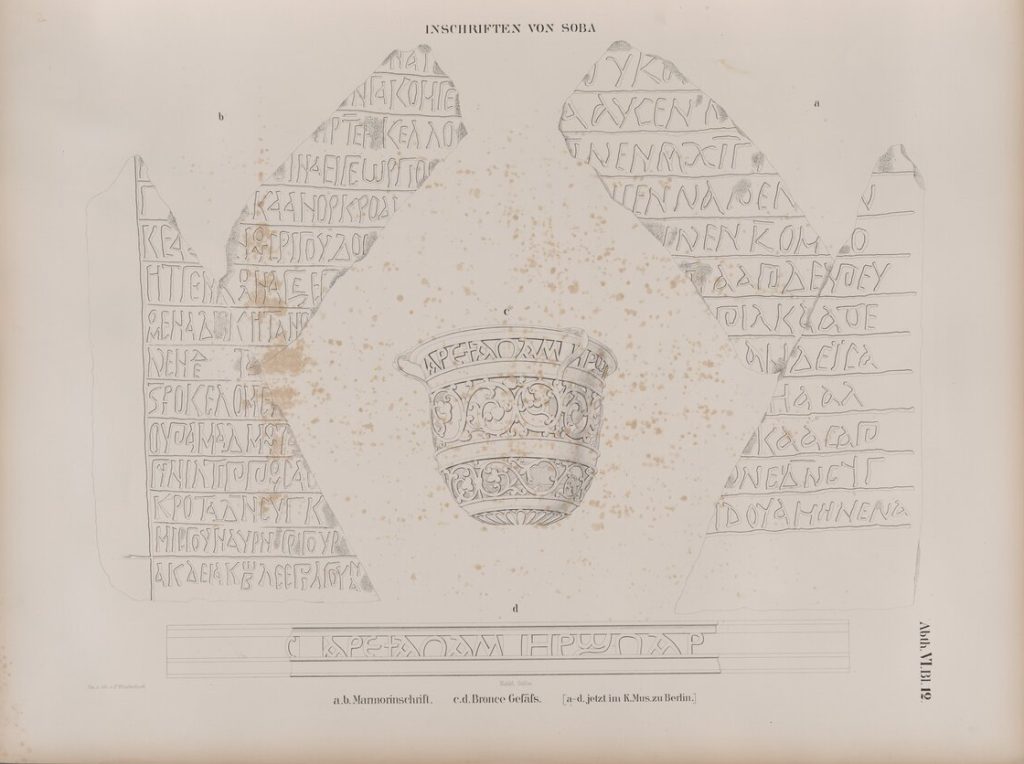

In addition to Old Nubian, a surviving Psalm translation and reports by medieval Arab geographers show that a Greek-based Beja writing system was also used. An inscription from Alodia suggests the existence of another Greek-based ‘Soba Nubian’ writing system, possibly drawing from Ge’ez or Meroitic.

All this paints a picture of a diverse written culture, where Greek was creatively mixed with other scripts to develop accurate ways of recording local languages.

The Christian Nubian kingdoms also became key trading partners for the Muslims of Egypt, resulting in a rise of Arabic trade documents that laid the groundwork for what would become the region’s next dominant literary language.

Fur and Funj Sultanates

By the 15th-century, plague, civil wars, and Mamluk invasions spelled the end for Christian Nubia and its Greek-based literary culture. Former Christian Nubian territory was divided among small Islamic chieftaincies. To their west, in modern-day Darfur, the pagan Daju Kingdom had been replaced by the Tunjur Sultanate. Thus began a process of religious shift that would soon encompass the whole of north Sudan: the shift to Islam.

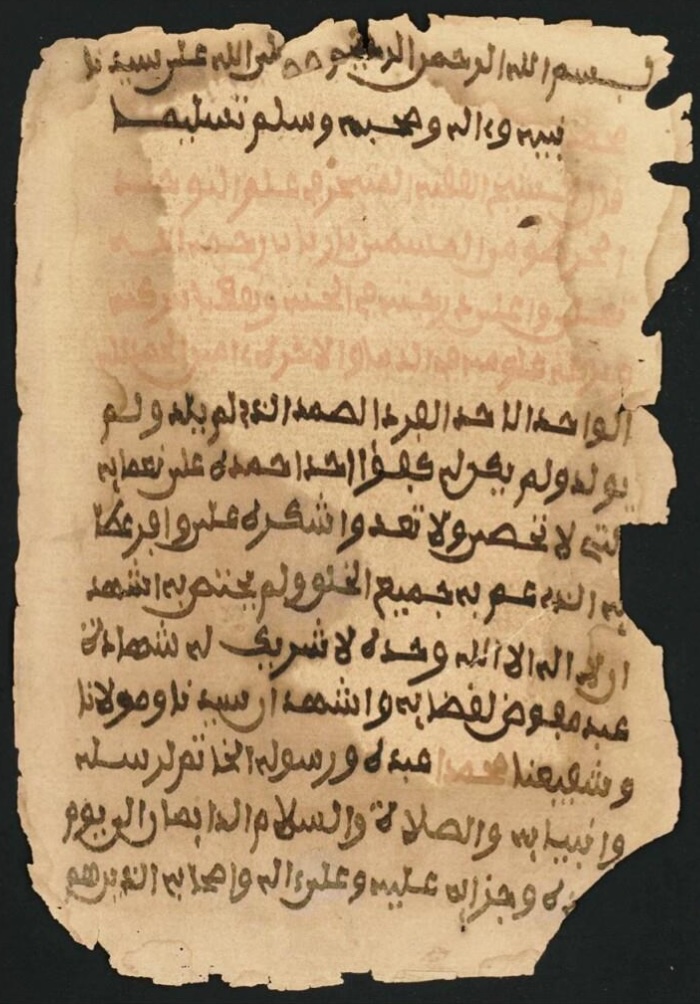

By the 16th-century, the new local Islamic elites consolidated their power in the form of the Fur Sultanate in Darfur and the Funj Sultanate in most of former Christian Nubian territory. Both sultanates were dependent on complex systems of land distribution and trade relations with the Arab Muslim world. They were also home to a new class of fuqahaa’ (holy men), who used Arabic as their sacred language, and were eager to pursue status and spread their faith.

Thus, like previous eras, Fur and Funj rulers adopted the language that they considered most prestigious: Literary Arabic, or fusha. The majority of documents that survive from these sultanates are land contracts between nobles, drawn up by fuqahaa’ and mainly written in fusha. Some of these documents give occasional glimpses of what we now call Sudanese Arabic, using terms like zol for ‘person,’ hinting at the spread of colloquial Arabic as a new, spoken lingua franca. That said, for the most part, local non-Arabic languages continued to dominate among elite and lay people alike.

These holy men’s access to the wider world of Arabic-Islamic literature also inspired new genres of writing, including history books like Muhammad wad Dayf Allah’s Kitab at-Tabaqat and theological works like Shaykh Arbab al ‘Agayid’s al Jawahir.

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (Latin)

Until the 19th-century, Arabic was the only literary language used in the region. This changed with the British conquest of Fur and Funj territory and the establishment of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. While colloquial and Literary Arabic continued to be popular, British colonialists also introduced English as a new elite tongue, and by extension, the Latin alphabet as a new way of writing.

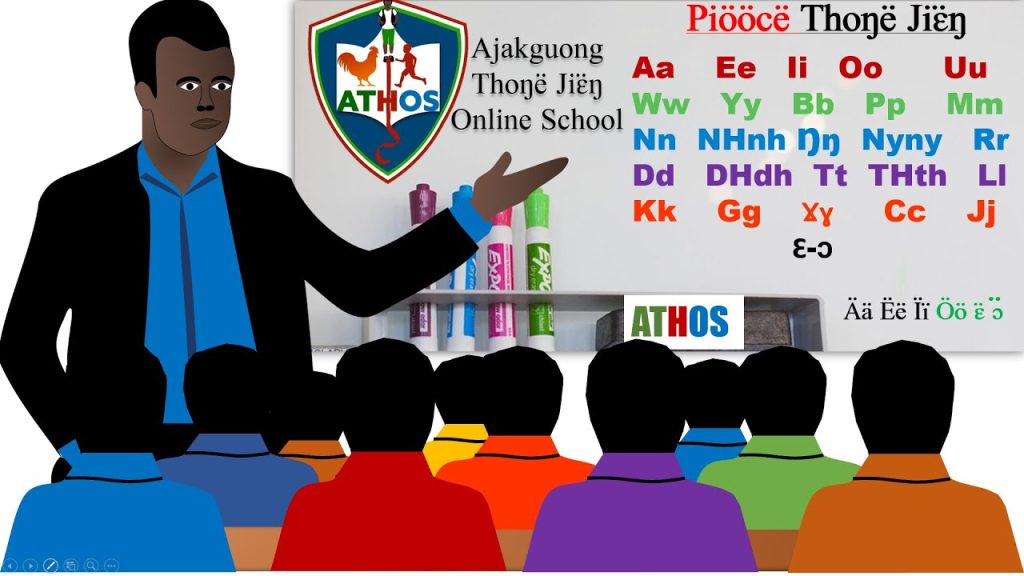

British colonialists employed a divide-and-conquer strategy meant to isolate north and South Sudan. Part of this was the Rejaf Conference in 1924, where colonialists devised Latin-based alphabets for South Sudanese languages with the intention of combating the spread of colloquial Arabic. The alphabets created then still play a role in how South Sudanese languages are written today.

Republic of Sudan (Arabic, Latin, Nubian, Zaghawa)

The language policy of English colonialists came to shape the written culture of post-independence Sudan. Northern Sudanese politicians used Literary Arabic and English, and banned the use of Latin alphabets to write South Sudanese languages in the name of decolonization. Thus, postcolonial policy politicised Arabic as a nationalist script.

For some non-Arabic language speakers, this was embraced, and they wrote their non-Arabic languages in the Arabic script, although no systematic method ever reached widespread acceptance. For others, it inspired the use of original alphabets as resistance.

In the 1950s, Zaghawi schoolteacher Adam Tajir created an alphabet for the Zaghawa language based on Zaghawi animal brands instead of Latin or Arabic writing. The script continues to be taught and used by Zaghawi language activists who seek to revive their language and counter Arabicization. In the 1990s, Nubian-language speakers made a similar move, reviving the use of the Greek-based Nubian alphabet for their languages, although written in a new, highly Latinised style.

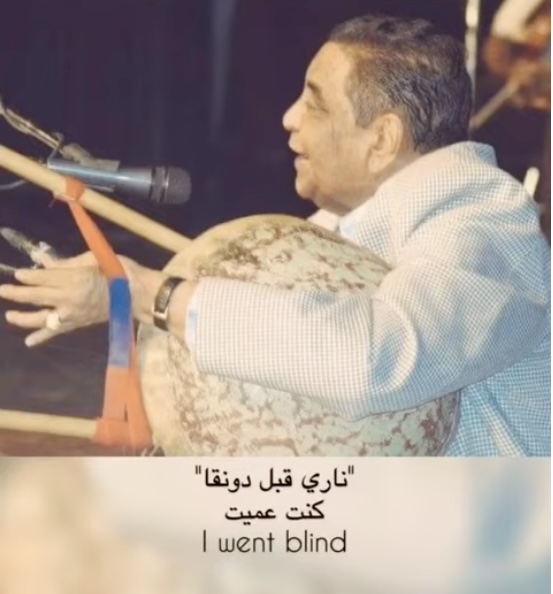

By the 21st-century, post-independence education efforts led to an explosion in Sudanese literacy, while the digital age opened avenues for a new world of informal writing uncontrolled by the state. This contributed to more writing of indigenous Sudanese languages and colloquial Sudanese Arabic, which has become the majority language for Sudanese regardless of background. Colloquial Arabic poetry, Dongolawi song translations, and Midob stories are now shared without the elitist barriers of conventional publishing, leading to the most diverse era in the history of Sudanese writing.

This intricate history of writing reflects Sudan’s reputation as the microcosm of Africa. The shifts among the elite in the region mirror broader regional trends, where religion and politics also shaped writing. This long history continues to inspire Sudanese people, who have entered an era where elites aren’t the only ones writing, and more languages and scripts – however informal – can be used than ever, recording the breadth of Sudanese culture and thought for prosperity in a way our ancestors never could.

500WM Columnist Hatim Eujayl is a Sudanese-American writer involved in various projects to promote Sudanese culture. His most famous works include the Sounds of Sudan YouTube channel, the Geri Fai Omir Kickstarter, and the Sawarda Nubian font. More of his writing can be found on his Substack, ‘My Sudani-American LiFE,’ where he discusses Sudanese literature and cinema. He can be reached on Instagram @massintod or by email at arbaab@hatimeujayl.com