The Nubian Language Family: From Halfa to Kordofan

Alley in central Dongola, one of the best-known cities in Sudanese Nubia. Image source: Bertramz, Wikimedia Commons

Although Arabic dominates today, Sudan remains ethnically and linguistically diverse. The more than 100 languages spoken across the country reflect millennia of migrations and political shifts, weaving a complex and diverse social fabric. One of the best-known threads in this tapestry is the Nubian language family, prized for its association with Sudan’s most famous historical sites.

Unfortunately, this interest in the Nubian past is not always matched with knowledge of the Nubian present. These languages are often lumped together as ‘rutana,’ Arabic for ‘gibberish,’ erasing their diversity and demoting their status.

The story of these languages and the nearly 1 mn people who speak them serve as a microcosm for the ways climate, politics, and economics shape Sudanese history.

Nobiin (Halfawi/Sikkotawi/Mahasi)

Meaning ‘language of the Nubians,’ Nobiin is spoken by 100,000 people in the Wadi Halfa, Sikkot, and Mahas areas of Sudan, as well as half a million Fadicca Nubians in Egypt.

In the medieval period, Old Nubian, an ancient form of Nobiin, was the language of governance and religion across most of what we now consider Sudan. It was written with a modified form of the Greek alphabet, which is sometimes still used to write the language today.

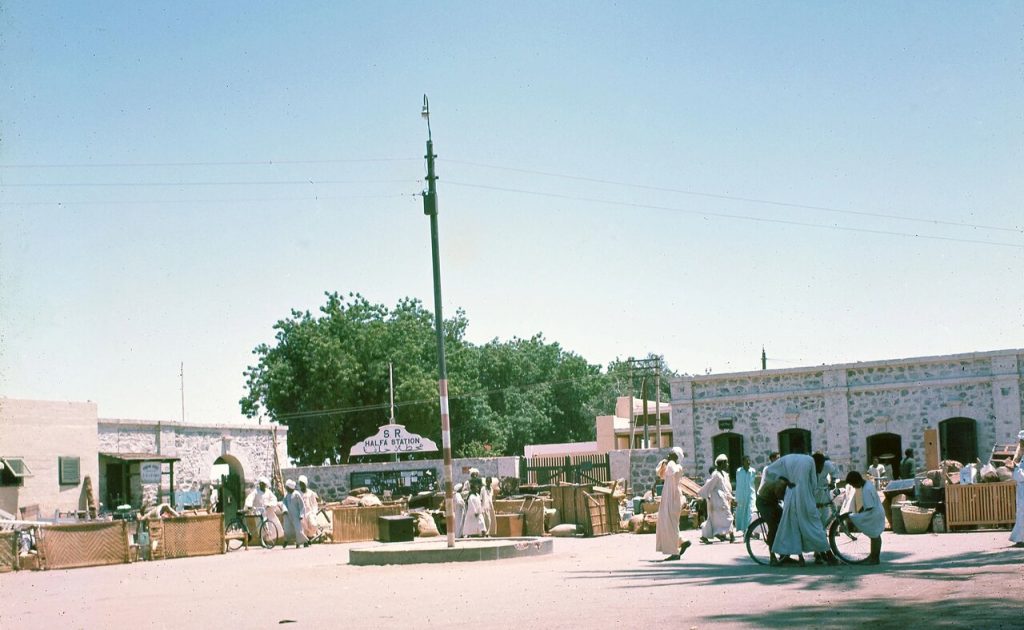

A photo of Wadi Halfa station, taken in 1960 by the Archaeological Survey of Sudanese Nubia before the flood.

Image source: AJ Mills

The language remained central in Nubian life well into the 20th-century. In the 60s and 70s, Nobiin speakers and musicians such as Mohammed Wardi and Al Balabil became musical icons, performing in both Nobiin and Arabic. Non-Nubian academics like Awn Al Shareef Gasim also began studying Nobiin’s impact on Sudanese Arabic.

The 1964 flooding of Nubia and forced expulsion of its people, however, dealt a severe blow to Nobiin’s survival. This traumatic event pushed Nubians into Arabic-speaking communities where indigenous languages continue to be stigmatised.

As a result, the language is now considered endangered. In response, Nubian activists, including Sudanese scholars Muhammad Jalal Hashim and Nubantood Khalil, have created initiatives to preserve and teach Nobiin.

Although many young Nubians are switching to Arabic, others feel the need to preserve their indigenous language. Today, Nobiin remains a language of daily life, poetry, and the vibrant contemporary Nubian music scene.

Andaandi (Dongolawi)

Meaning ‘our language’ or ‘the language of our home,’ Andaandi is the native language of the 35,000 Danagla living in Dongola and its surrounding areas.

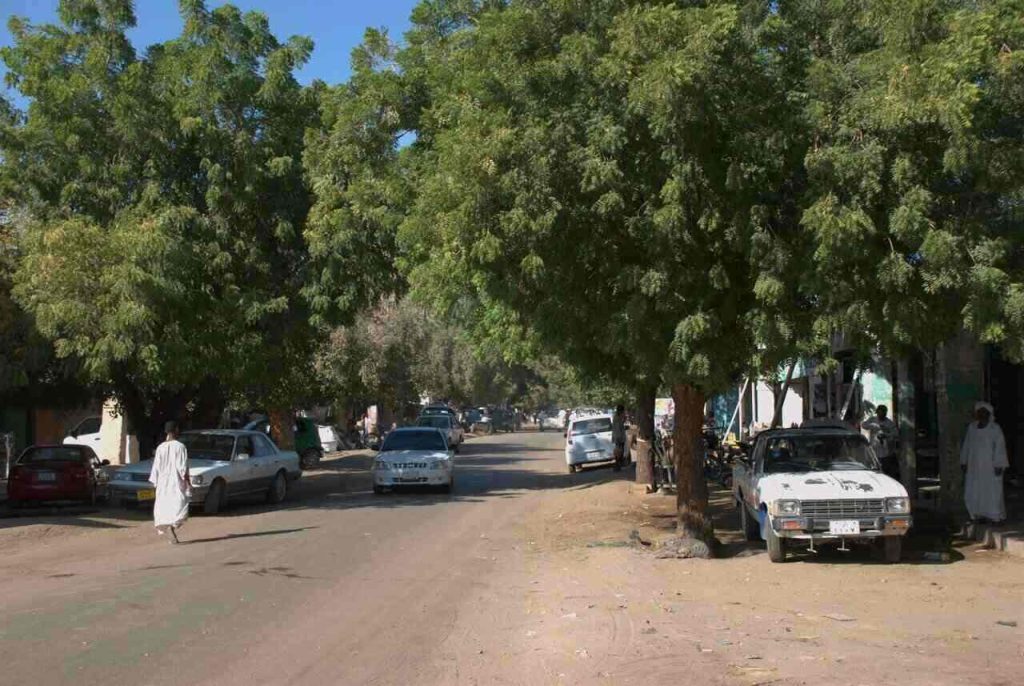

The market in Dongola in 2008.

Image source: Bertramz, Wikimedia Commons

Andaandi’s connection to the land of Dongola stretches over 1,600 years ago back to the kingdom of Makuria. The capital of this Christian kingdom was Old Dongola, where Old Andaandi was used as a spoken language. Due to the fall of the kingdom in the 15th-century, many Andaandi speakers migrated north to today’s Dongola as well as Aswan, establishing the Kenzi community in Egypt, whose Mattokki language is usually considered one with Andaandi.

In the 19th-century, European authors Joseph Russegger and Robert Hartmann described Sudanese Arab tribes south of Dongola speaking the language. This suggests Andaandi once had broader influence, although increased Arabisation and urbanisation have now made it an endangered language.

As is the case with Nobiin, Danagla have responded by launching initiatives to promote their linguistic heritage. This includes a variety of YouTube channels dedicated to teaching Andaandi, as well as books like Nobin Basaar, which document and comment on Andaandi poetry.

Tid-n-Aal (Midob)

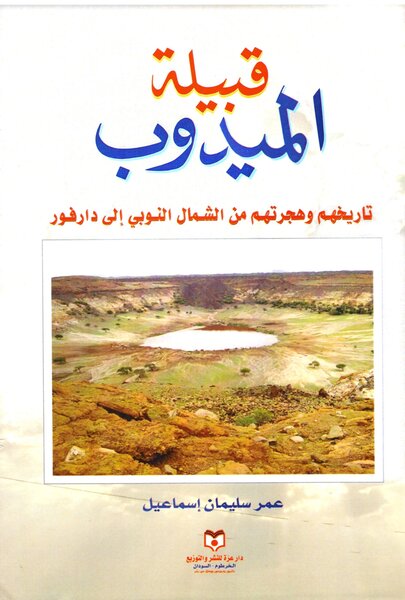

Meaning ‘mouth (language) of the Tid,’ Tidnaal is spoken by 50,000 people in the Midob Hills in northern Darfur, particularly in the city of Al Malha. Unlike the Nobiin and Andaandi-speakers along the Nile, the Midob traditionally practice pastoralism alongside agriculture, and retain a royal family.

The origin of the Midob is disputed. In the 2000s, an advisor to the Midob king claimed the tribe migrated from Dongola after the fall of Makuria. At the same time, unlike Mattokki, Tidnaal is not mutually intelligible with Andaandi. Thus, some scholars argue instead that the Midob migrated from a Nubian homeland in north Darfur due to desertification long before Makuria fell. Despite this, they would still have had contact with the Christian Nubian states, which is evident in Tidnaal vocabulary.

Tidnaal remains a stable language today, although it is not written nor officially recognised. Despite its vitality, it hasn’t received the same academic interest as Nobiin or Andaandi. A notable exception is a book titled The Midob Language by Ishaq Abdarrahman, published by the Sudanese National Council for Cultural Heritage and the Promotion of Local Languages in 2021.

Ajangwe (Hill Nubian)

Meaning ‘language of the Ajang,’ Ajangwe refers to at least seven languages spoken by over 70,000 people living in 18 communities in the northern Nuba Mountains. The largest Ajangwe languages include Unchuwe, Kadaru, Dalang, and Karko. Like most languages in the Nuba Mountains, Ajangwe varieties are largely understudied, and many are endangered. Back in 2019, in a historic example of pan-Nubian collaboration, Nobiin-speaking and Ajangwe-speaking activists in the Nubian Language Society worked together to combat this, developing a writing system for the Ajangwe languages based on the Old Nubian alphabet.

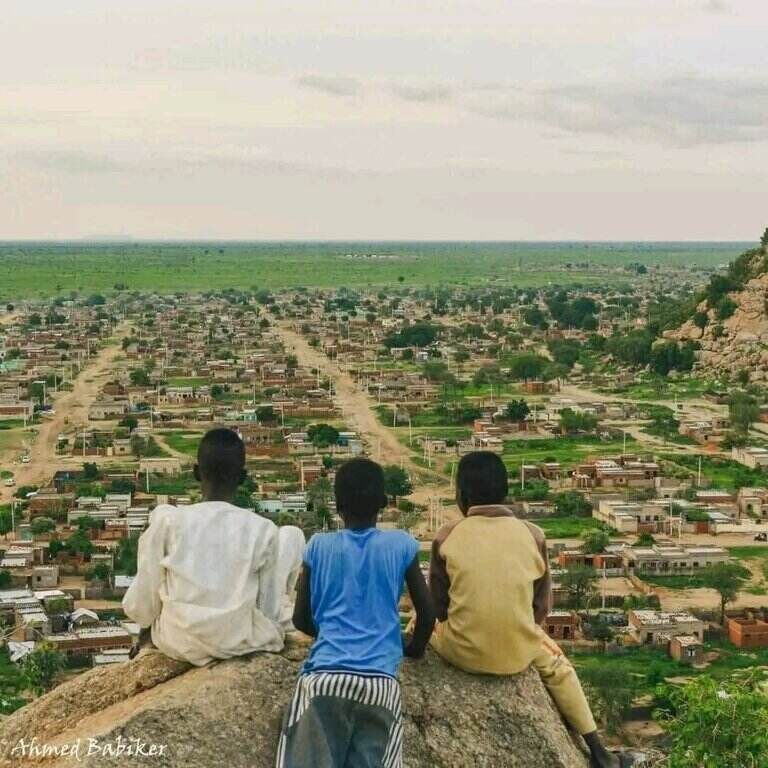

Three kids looking out over the city of Dalang in South Kordofan, one of the main Ajang communities.

Image source: Ahmed Babikir, Wikimedia Commons

As is the case with the Midob, the origin of the Ajang is disputed. Many Ajang claim to have migrated to the Nuba Mountains after the fall of the Christian Nubian kingdoms. This idea is echoed in local histories, such as the Turkish-era Sudanese book Makhtootat Katib Al Shuna (The Funj Chronicle), which describes the ‘Anaj Nuba’ of the Christian Alodia kingdom migrating east to ‘the mountains of Kordofan.’

It is also accepted by academics such as Claude Rilly, who speculate that the migration of Nubian language speakers is what led to the Nuba Mountains’ name. Despite this, however, the majority of Nuba are not Ajang, and speak other, non-Nubian languages.

Other scholars argue that the Ajang split from Nobiin and Andaandi speakers much earlier, due to the immense diversity among Ajangwe languages, as well as the major differences between them and the Nile Nubian languages. Based on these factors, they theorize the Ajang migrated from the northern Darfuri Nubian homeland at least 2,500 years ago.

This doesn’t mean they were isolated from their linguistic siblings along the Nile, however. Some Ajangwe languages show Coptic influence in the words for days of the week, confirming interactions with Christian Nubians. Old Nubian writing has also been found in Kordofan, additional evidence that Nile Nubians would visit west Sudan.

Extinct Nubian languages (Birgid, Haraza, Soba)

The ten languages listed above already represent an impressively diverse landscape. But this is a mere shadow of the larger Nubian-speaking continuum that once existed throughout riverine and western Sudan. Many of these varieties have gone extinct, being primarily known from a handful of documents.

Among these is the Murgidi language, spoken by the Murgi/Birgid people in southern Darfur up until the 80s. Now, it remains a memory among older Birgid and is no longer spoken in daily life. Jalal Hashim has reported that some young Birgid are interested in reviving the language.

More obscure is the Haraza Nubian language of North Kordofan, known from only 36 words recorded in the colonial area. Like Ajangwe, it is also speculated to have reached Kordofan due to post-Alodia migration.

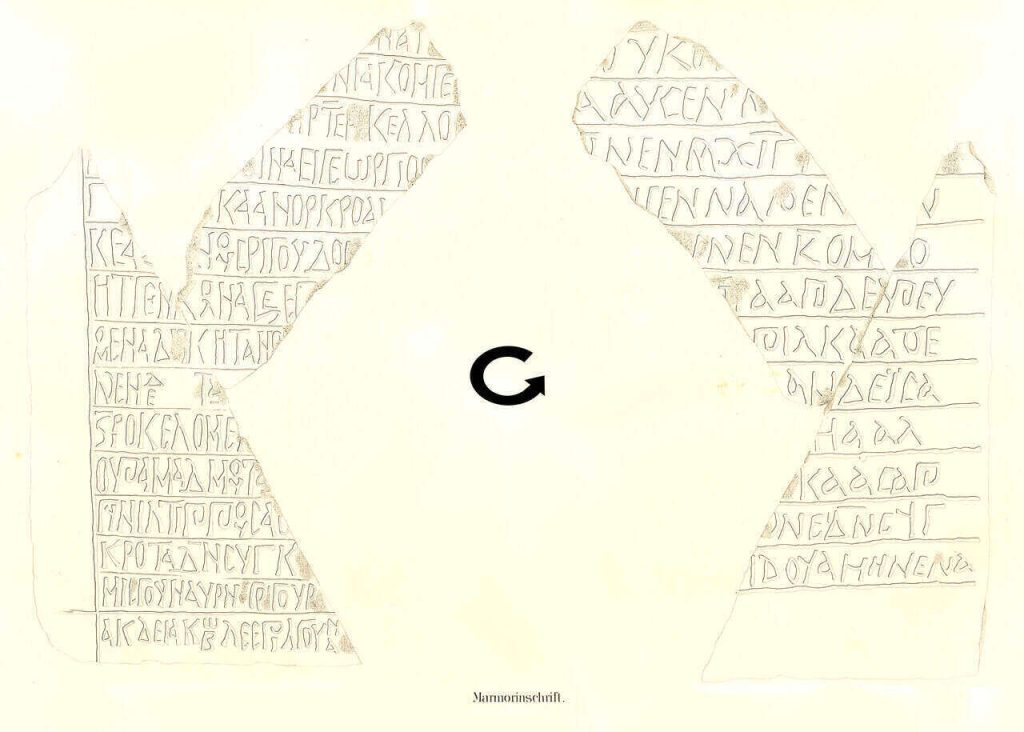

A marble inscription from Soba, written in an undeciphered Nubian language.

Image source: LeGabrie, Wikimedia Commons

The language of the Alodian capital Soba is also poorly understood. Expert Vincent van Gerven Oei has noted that the language resembles Old Nubian and Old Andaandi, although the Alodian writing system contains many mysterious letters scholars can’t read yet.

While the Nubian languages may seem small in Sudan today, their immense diversity and wide geographic distribution testifies to a history where the family once dominated along the Nile and west of it. This wasn’t in the form of one united tongue, but rather a mosaic of more than a dozen languages, moving from place to place due to changes in climate and politics.

The different stories about the Nubian languages are a microcosm for the astounding complexity of Sudanese history, bridging regional and tribal gaps. Their unfortunate endangerment too reflects the course of Sudanese history: Christian Nubian sovereignty collapsed, and economic power in the region shifted towards a Muslim Arab-dominated Nile confluence.

The efforts to revive them, in turn, represent a vision of a plural, multilingual Sudan, where languages and ethnicities can coexist without subsuming each other, just as in the pre-colonial past.

It remains to be seen whether this will be achieved. Regardless, however, the Nubian languages should be appreciated as a unique piece of human heritage, and a key component of the Sudanese story.

500WM Columnist Hatim Eujayl is a Sudanese-American writer involved in various projects to promote Sudanese culture. His most famous works include the Sounds of Sudan YouTube channel, the Geri Fai Omir Kickstarter, and the Sawarda Nubian font. More of his writing can be found on his Substack, ‘My Sudani-American LiFE,’ where he discusses Sudanese literature and cinema. He can be reached on Instagram @massintod or by email at arbaab@hatimeujayl.com