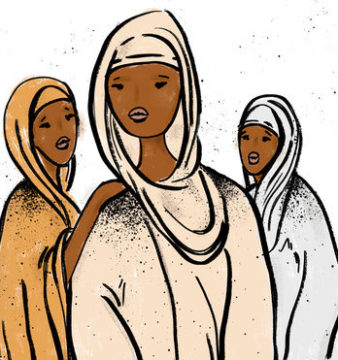

COVID-19 Lockdown: What Will It Mean For Sudan’s Most Vulnerable?

Triggered by the recent COVID-19 outbreak, a wave of class consciousness seems to have rippled across the globe with the same proliferative contagion as the virus, whilst the health crisis continues to highlight and expose the inequalities suffered by working class populations everywhere.

Whether it be the US, where the death rate has hit black Americans disproportionately owing to the community’s relatively low socioeconomic background, or India, where the shutdown has left thousands of migrant labourers unemployed and stranded, it is clear that the status quo is changing. The realisation that the protective measures advised against contracting the virus are infeasible for the majority is setting in, giving rise to a worldwide, working class anger to brew beneath the surface of this pandemic and now, as the number of cases are rapidly rising, it is Sudan’s turn to feel it.

The first COVID-19 case was reported in Sudan on 13 March 2020, bringing with it a series of government policies as a public health state of emergency was announced. It began with the halting of visa issuance for certain countries then escalating to the closure of all schools and universities, the shutdown of the country’s only international airport, and more recently the introduction of a curfew from 6 am to 6 pm, followed by the announcement of a three-week lockdown in Khartoum, which began on Saturday, 18 April 2020. Action to flatten the curve was fast – with only 80 ventilators and already impossibly scarce ICU beds, the debilitated healthcare system is in no shape to absorb a mass number of cases.

These decisions, though necessary to contain the outbreak, have brought on their own set of consequences, disproportionately affecting the more marginalised factions of society. As dormitories were emptied and a ban on interstate travel was enforced preventing them from going home, large numbers of out-of-state university students were rendered homeless, making them especially susceptible to contracting the virus.

As businesses close their doors in the absence of a social safety net, many workers are left not knowing where their next paycheck will come from. Khartoum’s tea ladies, who receive the bulk of their customers after sundown, have had their earnings significantly stemmed by the 6 pm curfew. Those reliant on few and far between public bus services are forced to wait for hours in crowded stops, increasing their likelihood of infection. Those who rely on the day’s work in crowded markets for their income, now shoulder the additional burden of possibly falling ill; however, weighing the odds, the overwhelming opinion is that they would rather take their chances with the virus over the definite option of having no food or utilities should they stay home. To make matters worse, the crisis saw prices of face masks and hand sanitisers sky-rocket, further diminishing any prospect workers had of staying safe whilst performing necessary tasks.

However, in the midst of the crisis, a social media campaign emerged, calling for free internet services to be provided in Sudan, in an effort to encourage social distancing during the outbreak. Though well-meaning, the sentiment behind the hashtag #free_internet_sudan worked only to further underline the already stark reality of the wealth and class disparity issue the country has been simmering in for decades. In what seemed to be an emulation of wealthier nations, which have taken the initiative to provide free internet services for their citizens, the reality of Sudan was overlooked by the campaign. The campaign slogan, ‘If internet is free, you will stay at home in safety’, willfully ignores the fact that the vast majority of the population live under the poverty line with a minimum wage of a meagre SDG300 (chalking up to less than the cost of dessert in a high-end Khartoum café) and that whilst many middle to upper class Sudanese may have access to passive income, most of the nation is comprised of workers relying on each day’s labour for sustenance, internet being the least of their concerns. The demand for what is a relative luxury at a time like this epitomizes the aristocratesque isolation bubble in which the Khartoum elite resides.

The concept is perfectly illustrated in affluent Khartoum neighbourhoods – it is not uncommon to find a villa flocked by flashy cars and serviced by a small army of servants, cooks and drivers to be neighboured by a dilapidated, makeshift shack of gunny sacks and scraps. Whilst the television and radio blare out instructions on the correct duration of hand-washing to prevent the spread of the virus, the inhabitants on the other side of the wall have no access to running water.

Now amidst talks of a total three-week lockdown, and as cases are expected to soar to approximately 255 by mid-May, some questions rise to the forefront. Is the government doing enough to protect the disenfranchised amid this outbreak? Or are society’s most vulnerable about to be made even more so?

Khansa Al-Bashier is a young Sudanese writer with an interest in all things literature, history and religion. When not writing, she can be found pursuing her education as a medical student.