The unconventional city

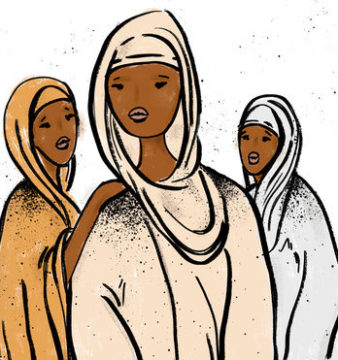

I grew up in a cosmopolitan Khartoum, welcoming to outsiders. And yet now it seems that Sudan exists behind an iron curtain, out of step with the rest of the world. When I think of my childhood, I think of our house in Street 7, in what was then known as the New Extension and now is referred to as Amarat. I lived in it from when I was born until I was nineteen, a long, steady time. Years afterwards in Scotland, in Jakarta, in Dubai, I would dream of that house as if I had not left it, as if I still had a right to be there. Black speckled tiles, the steps down to the garden which in mid-day could scorch my bare feet, my aunt in her white Tobe stepping out of a car, carrying boxes full of Ka’ak or covered dishes of Kisra and Mullah. Physically in terms of sensations, in term of aesthetics I am rooted in Khartoum and to that particular house. I return to it in my fiction, it is my base; synonymous with a private idea of Sudan. But the house, like the city, was porous to the rest of the globe, open to a multitude of cultures.

The Jordanian Embassy was to the

left of our house. At daybreak, a man in uniform would climb up to the roof and hoist the flag. My brother and I slept on the veranda, across from the roof of the embassy and often the first thing I saw in the morning was that blur of flag unfurling.

In the identical house to the right, lived an American family. Once a week they hosted a baseball game in the square in front of our houses. Its ground was littered with broken glass that threatened the wheels of my bicycle. Somehow though, the Americans managed to make a baseball pitch out of it. My brother and I stood in the street watching the game, following the thud of bat on ball. The few people driving past craned their heads to look, Southern bicycle riders stopped and stared. This was siesta time, shops were closed; the temperature was in the forties and the Americans kept running, kept batting until the roar of ‘Home run!’

Indoors, if I lowered the toilet cover and stood on it, I could peer out of the window at the veranda of our back neighbours. They were Syrian-Christians, the Shawam who were the backbone of Khartoum’s business sector. I watched a dewy eyed mother fuss over her teen-age sons; a family who unlike us celebrated Christmas and didn’t fast in Ramadan. Yet they were Sudanese too – in how seriously they took their social life, in their accents, in how they understood that Khartoum was fertile and brimming with potential. A city that, I hope once again would be true to itself, spacious and languid, close-knit and unconventional; a place to be innovative and adventurous.

Leila Aboulela’s latest novel Lyrics Alley, set in 1950s Sudan, was inspired by the life of her uncle, the poet Hassan Awad Aboulela. Lyrics Alley is the Fiction Winner of the Scottish Book Awards. It was long-listed for the Orange Prize and short-listed for a Regional Commonwealth Writer’s Prize. Both of Leila’s previous novels The Translator and Minaret were long-listed for the Orange Prize and the IMPAC Dublin Award. Leila Aboulela is a winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing and her work has been translated into 13 languages.

welll writting ,engaging your beautiful memories of sudan just reminded me how beautiful place was it .

Sudan is still a beautiful place, it always was, it always will be.

It is simply your own perception and what you make of it.

Great peice of writting. Shared by Laura Man who made me love KHartoum in its worth situation.