When 500 Words Magazine met Sudalove

On a normal day in Jazaar road in Riyadh, Khartoum we saw a lady bring an old wall to life. That wall went from a beige empty surface to a colorful piece of art that is familiar to the streets of Khartoum.

That person was none other than Assil Diab (aka Sudalove). A Sudanese graffiti artist who lives in Doha, Qatar. We tried to curb our excitement, took a deep breath and had a chat with her about the journey she began to make the city a big art gallery.

Assil Diab (Credit: Ahmed Shaheen)

500 Words Magazine: Is there a specific message you’re trying to send using your art?

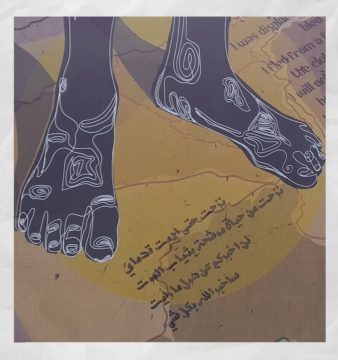

Sudalove: People will interpret what you’re saying in your visual art based upon their own worldview. However, there are many messages I am trying to convey in my art. These messages draw on titles and issues in our surroundings and environment which include recycling, life/death, religion, politics, poverty, race, and even financial issues. When it comes to my abstract art, I feel like abstract art gives you the freedom to explore the artwork and assign your own meaning to the piece. Abstract art is open to interpretation, and that is one of the beautiful things about it.

Graffiti is such a male-dominated space; how do you find the feminist angle of your work, in taking over this space for yourself?

Standing in 90 degrees heat, physically working with paint fumes everywhere, is what you go through as a graffiti artist in the summer for instance. The fact that there are fewer females in the graffiti industry than there are men is because statistically, men are more prone to getting in trouble than women.

I think most people are taken aback by the fact that I am a Sudanese, Muslim, female taking up this rather masculine/macho street art form. I’ve always been a tomboy so it was easy for me to fit in the genre. I could defuse a situation with police just by being there.

My attitude has always just been that I focus on my work and not what race or gender I am, but eventually I became rather interested to put Sudan out there on the map, especially in the street art scene.

Assil next to one of her pieces in Doha (Credit: Timothy Carr)

Do you ever have issues in the streets specific to being a woman?

It depends which country I’m tagging in. But it’s mostly harassment from men and people who think I want to start war by writing political stuff everywhere. This older man once stopped me on Al Matar (Airport) Street in Khartoum, I was tagging a quick throw-up of “K-Town” and he accused me of writing a statement of opposition against the government and obstructing, before I had to school him on the English language and explain what “K-town” meant. But that was the only time I got into it, most of my other bombing experiences were all love

Sudan and Sudanese-ness seem linked to your work in a lot of ways, especially with your name –

Graffiti artists’ work is shaped by those perceptions, experiences and the world around them. And nothing may be more impactful than where the artist is from. The street/graffiti name “Sudalove” I go by represents my home country, Sudan, since my work touches upon many subjects and places, I wanted to take Sudan with me everywhere. My identity does not rely on being Sudanese or a female, but I like bringing what I know back home and taking home with me where I go and whenever I leave a mark.

How do you navigate the complexities of identity, being Sudanese but spending most of your life in Qatar?

I was born in Bucharest, Romania, grew up in Qatar, and obtained my BFA from Richmond, Virginia. I think I appreciate Sudan because I do not live there. It has strengthened my relationship with it because I keep missing it. So whenever I am there on a little vacation I try to tag as many walls as I possibly can. Tagging and bombing is different in Sudan because there is much more of a pedestrian culture than we have here in Qatar. It’s much more intimate in Sudan because people stop and get up close with the art.

At first, I was just trying to do something that people would look at and be like “Oh that’s cool.” But then I realized I wanted to affect people just like the first tag I did back home and the response I got from everyone – that affected me. I wanted to inspire people to love their community.

When I am Assil Diab, I’m merely a graphic designer residing in the Middle East, but when I am Sudalove I have an individual identity that you self-select and self-categorize, an identity related to other social groups from and outside the art scene.

Art of the street in contrast to art in a gallery is very direct as the public have a way of accessing it that most of the time they normally wouldn’t – does this factor into you choosing graffiti over other methods?

I choose to practice my artwork in graffiti rather than other mediums because it is simply public art. When I paint a wall I am opening a dialogue with the public, in contrast to keeping some artwork in a gallery where I would be limiting my audience. Graffiti in the other hand is unlimited audience, I’m speaking to the world – it is my way to express environmental, social and political messages and a whole genre of artistic expression merely using spray paint. Graffiti can simultaneously serve a public good through its nuanced social commentary and its’ shapes and colors.

There is an explosion of street design in Khartoum now – where do you see or hope to see this going?

That is true, I’ve seen lots of murals painted in the last year. If Graffiti is put in a good cause, it can do good for social development, founding art schools in low-income neighborhoods and partnering with the police to paint murals in neglected and shabby areas.

Personally, Khartoum to me is one large worn-out canvas that yearns for some color, and also because the street art culture is almost non-existent, that’s why it has been my favorite place to paint.

Picture Gallery

Sudalove paints anywhere from commissioned walls, T-shirts, to cars. Check out her work at her Website, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.